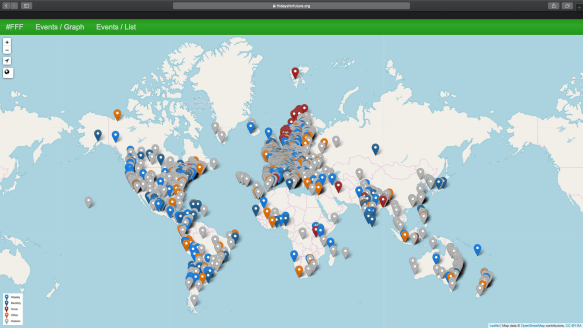

School students are protesting today about the failure of politicians to take serious action in response to climate change. They are calling for action. The Global Strike for Future grew from 16 year old Swedish student Greta Thunberg‘s decision to strike on Fridays outside the Swedish parliament. She has been joined regularly for Friday protests by students in Germany, Belgium, Britain and France. Today’s global protest is happening in 112 countries including Australia. “Pupils from hundreds of schools in over 55 cities and towns across Australia are using the action to call on all politicians to stop Adani’s coal mine, say no to all new fossil fuels and power Australia with 100 per cent renewable energy by 2030.”

School students are protesting today about the failure of politicians to take serious action in response to climate change. They are calling for action. The Global Strike for Future grew from 16 year old Swedish student Greta Thunberg‘s decision to strike on Fridays outside the Swedish parliament. She has been joined regularly for Friday protests by students in Germany, Belgium, Britain and France. Today’s global protest is happening in 112 countries including Australia. “Pupils from hundreds of schools in over 55 cities and towns across Australia are using the action to call on all politicians to stop Adani’s coal mine, say no to all new fossil fuels and power Australia with 100 per cent renewable energy by 2030.”

A protest is obviously evidence of a dispute, in this case between politicians and young people, most of whom are not yet allowed to vote. It is hard for people without a right to vote to persuade democratically elected politicians. The power imbalance between the primary parties to this dispute is obvious. However, if there is, as is expected, a significant turn out in numbers, a strong message will be sent to politicians about what future voters think about their performance on climate change. The dispute has already sparked reaction from politicians in Australia, with the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, Commonwealth Education Minister and NSW Education Minister all making public statements calling for students to stay in school and not participate in the strike. The Deputy Prime Minister said in parliamentary question time that “the children should be staying in school to learn about Australian history, to learn about Australia geography“. Prime Minister Scott Morrison has called for less activism and more learning in schools. Essentially, none of these responses address the substantive concerns of the protestors, instead concentrating on the right to protest where it conflicts with the policy of compulsory school attendance. Other politicians have supported the children’s right to protest, including the ACT Education Minister.

Another argument raised against the protest is that because the people protesting are children, they are essentially being “politicised” and used by adults to push a political agenda. Students have responded assertively against such claims, reinforcing that they are expressing their own concerns. This argument plays upon the power imbalance between the parties, because the people protesting are being told that their message is less persuasive because they lack capacity to form a truly independent opinion in the way that an adult can.

The dispute has spread well beyond the two groups of politicians and school students who wish to protest. Schools have been divided in their support or non-support of their students attending, media coverage reveals a range of views for and against, and parents and children have been negotiating their way around whether or not they are allowed to or supported to participate.

The opportunities for the application of conflict management and resolution processes in this context are infinite.

- Within families, the opportunity to engage in meaningful, respectful discussions about the issues of climate change action and protesting about it in school time has been taken in many families. There has potentially been enormous growth in the skills that both children and parents have chosen and developed in these dialogues.

- Similarly, students, teachers, parents, and school principals have all had the opportunity to discuss the issues, negotiate possibilities, and communicate boundaries within school communities. Thinking about ways to enable different points of view to be expressed, and to manage conflicting opinions, power imbalance, and mass protest must have been an enormous challenge within schools. There is always the choice to use power to say “no”, but the civil disobedience on a mass scale that might follow then also has to be dealt with. It will be interesting to see whether schools take the opportunity for a “teachable moment” to discuss protest, school attendance and climate change action by politicians and ordinary people, and effective ways to manage conflicting points of view.

- Politicians have an opportunity to decide how to engage with the message that the people they govern are sending them. They could decide to open a conversation, to think critically about how people under the age of 18 can meaningfully participate in political life, and to take a more collaborative approach to the conversation rather than the adversarial “for or against” approach that appears to have been adopted so far.

About the author: Sue Field is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Western Sydney University where for the past fourteen years she has taught elder law to undergraduate law students. Sue is also an Adjunct Associate Professor at Charles Sturt University, a Lead Investigator with the Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, a Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia, a Director of the Australian Centre for Elder Law Pty Ltd and a Distinguished Fellow at the Canadian Centre for Elder Law. Sue is co-editor of the Elder Law Review, the only refereed elder law journal in Australia. In conjunction with Professor Carolyn Sappideen and Karen Williams Sue has co-edited a recently released text on Elder Law and is working on a co-authored text on elder law for the layperson. Sue has published widely and presented at many international and national events.

About the author: Sue Field is an Adjunct Associate Professor at Western Sydney University where for the past fourteen years she has taught elder law to undergraduate law students. Sue is also an Adjunct Associate Professor at Charles Sturt University, a Lead Investigator with the Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, a Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia, a Director of the Australian Centre for Elder Law Pty Ltd and a Distinguished Fellow at the Canadian Centre for Elder Law. Sue is co-editor of the Elder Law Review, the only refereed elder law journal in Australia. In conjunction with Professor Carolyn Sappideen and Karen Williams Sue has co-edited a recently released text on Elder Law and is working on a co-authored text on elder law for the layperson. Sue has published widely and presented at many international and national events.