Alvedi Sabani and Kathy Douglas

Negotiation has always been a practical skill best learned by doing. For decades, negotiation education across law, business, and the social sciences has relied on roleplays and debriefing as its signature pedagogy. These activities remain powerful because they immerse learners in conflict scenarios, expose them to different perspectives, and create space for reflection, a point long recognised in negotiation scholarship on learning through experience and transfer of skills.

But the context in which negotiation is practised is changing.

Today, many negotiations happen online, through digital platforms, hybrid meetings, or technology-mediated environments. At the same time, universities are grappling with larger cohorts, hybrid delivery, and growing expectations that learning experiences be authentic, inclusive, and scalable. Against this backdrop, we have been exploring a simple question: can immersive technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) meaningfully extend negotiation pedagogy without replacing its core strengths?

This blog reflects on our experience using a VR negotiation simulation in higher education, and what it might offer educators working in dispute resolution, mediation, and negotiation more broadly.

Why revisit negotiation pedagogy now?

Negotiation education has long been anchored in experiential learning. Whether in law schools, business programs, or professional development courses, learners typically practise through roleplays followed by structured debriefing. This approach is effective because negotiation is not just about tactics or frameworks; it is about judgement, emotional intelligence, communication, and adaptability, which are capabilities that develop through cycles of action and reflection, as articulated in David Kolb’s experiential learning theory.

However, traditional roleplays also have limitations:

- They are labour-intensive to run well

- Quality depends heavily on participant engagement

- Experiences vary widely between groups

- Opportunities for repetition and skill mastery are limited

- Accessibility and equity can be uneven

At the same time, negotiation itself is evolving. Online dispute resolution (ODR), legal technology, and AI-mediated communication are increasingly part of professional practice. Students need opportunities to practise negotiation in environments that resemble how difficult conversations now occur in real workplaces.

This combination of pedagogical pressure and professional change prompted us to explore immersive learning as a complement to traditional approaches.

What does VR add to negotiation learning?

Virtual Reality is often associated with novelty, but its real value in negotiation education lies elsewhere. When designed carefully, VR can support three things that are difficult to achieve at scale with traditional roleplays: presence, consistency, and repetition.

In a VR negotiation simulation, learners step into a scenario where they are physically and emotionally “present” in the conversation. They sit across the table from a virtual counterpart who responds to their words, tone, and decisions. Facial expressions, pauses, and emotional cues all matter. Research on immersive learning suggests that this sense of presence and emotional engagement can be particularly valuable for developing interpersonal and professional skills

Equally important is consistency. Every learner encounters the same scenario, the same counterpart, and the same decision points. This allows educators to design learning and assessment around a shared experience, while still allowing individual agency in how the conversation unfolds.

Finally, VR enables repetition. Learners can replay the same negotiation, try different approaches, and immediately see how alternative choices change outcomes. This aligns closely with how complex skills are developed in practice: through cycles of action, feedback, and reflection.

The negotiation scenario

In our case, the VR simulation places learners in the role of a technology consultant meeting with a senior executive who is sceptical about a proposed organisational change. The executive is concerned about employee resistance, workload, and unintended consequences. The learner’s task is not to “win” the negotiation, but to work collaboratively toward a solution that addresses shared interests.

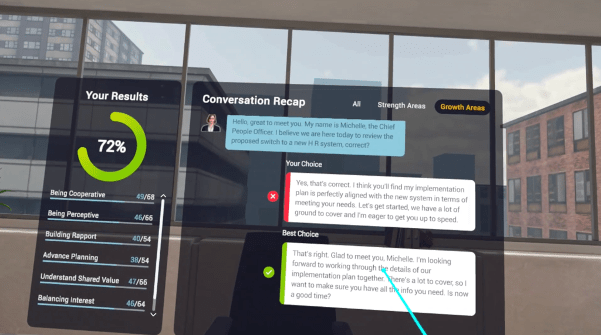

This framing is deliberate. The simulation is grounded in integrative negotiation, where the aim is to create value rather than claim it. Throughout the conversation, learners make choices about how to respond: whether to acknowledge concerns, ask clarifying questions, provide evidence, or push too quickly for agreement. Each choice influences the direction of the conversation and the executive’s reactions.

What makes this powerful is that learners experience the emotional consequences of their decisions. A dismissive response leads to defensiveness. A well-timed question builds trust. A failure to listen can derail the conversation entirely. These dynamics are difficult to convey through lectures alone, but they become immediately visible in an immersive setting.

Reflection remains central

One concern often raised about technology-enhanced learning is that it risks prioritising experience over understanding. We would argue the opposite: without reflection, VR is just a simulation; with reflection, it becomes learning.

In our design, the VR experience is always paired with structured reflection. After completing the simulation, learners receive detailed feedback, including a transcript of their conversation and indicators of strengths and areas for growth. They are then asked to analyse their performance, connect it to negotiation theory, and articulate how they would approach the conversation differently in the future.

This reflective component does several important things:

- It slows down the experience and turns action into insight

- It connects practice back to theory

- It legitimises “failure” as a learning opportunity

- It encourages learners to think critically about their own habits and assumptions

In many cases, students who struggled in the simulation produced the most thoughtful reflections. The technology does not replace judgement; it exposes it.

What did students experience?

Learner responses to the VR negotiation have been strikingly consistent. Many describe feeling nervous before starting, as they would before a real workplace conversation. Others note that the executive’s reactions felt “uncomfortably real”. These emotional responses are precisely what make the experience valuable.

Students frequently highlight three benefits:

- Confidence building – practising difficult conversations in a safe environment reduces anxiety about real-world negotiations

- Insight into their own behaviour – seeing how small choices affect outcomes is eye-opening

- Opportunity to improve – replaying the scenario allows experimentation without real-world consequences

Importantly, accessibility has also been a design priority. The simulation can be completed using a VR headset or on a standard computer, ensuring that no learner is excluded due to equipment or physical constraints.

Lessons for ADR and negotiation educators

Our experience suggests that VR is not a replacement for traditional negotiation pedagogy, but a complement. Roleplays, clinics, and live simulations remain essential, particularly for developing interpersonal sensitivity and peer learning. However, immersive simulations can extend what is possible, especially where scale, consistency, or access are challenges.

Several lessons stand out:

- Pedagogy must lead technology. VR works best when grounded in clear learning objectives and theory.

- Reflection is non-negotiable. Immersion without reflection limits learning.

- Blended approaches are powerful. Combining VR with roleplays, discussion, and debriefing enriches all elements.

- Staff capability matters. Educators need support to design, facilitate, and interpret immersive learning effectively.

Looking ahead

As negotiation increasingly takes place in digital and hybrid environments, it makes sense that negotiation education evolves alongside it. Immersive learning offers a way to rehearse difficult conversations, develop emotional intelligence, and build professional confidence in settings that feel authentic to contemporary practice.

For ADR educators, the challenge is not whether to adopt new technologies, but how to integrate them thoughtfully, in ways that preserve the reflective, human-centred core of the field.

Virtual Reality is not a silver bullet. But when used carefully, it can open new possibilities for learning how to negotiate well, ethically, and with empathy, skills that matter now more than ever.

Authors Biography

Dr. Alvedi Sabani is a Senior Lecturer and Program Manager of the Bachelor of Commerce at the College of Business and Law (CoBL), RMIT University, and the EdTech Project Lead. His research interests are broad and interdisciplinary, spanning artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud computing, digital transformation, electronic government, gamification, innovative pedagogy, and inclusive technology adoption. As a co-founder of the RMIT GamifiED Hub, Dr. Sabani has been instrumental in driving scholarly innovation in learning and teaching through gamification. This initiative has produced cutting-edge resources that enhance the student learning experience, aligning closely with RMIT’s strategic emphasis on Active, Authentic, and Applied learning.

Professor Kathy Douglas leads the College of Business and Law learning, teaching and quality portfolio including governance, student satisfaction, program development and innovation in pedagogy. She is an experienced Executive leader who has focused on developing transformative educational experiences and impactful research. She was a member of academic board for several years and in 2020 chaired the Higher Education Committee. Previously, Kathy was the Dean of the Graduate School of Business and Law at RMIT (2018-2022). She led a high performing school focused on industry engaged learning and research. Kathy was awarded the Vice Chancellor’s leadership award for Imagination in 2020 for her innovative practices. Kathy has a passion for impactful leadership that benefits students, staff and the communities that RMIT engages with, including industry. In 2025 she was awarded the Francis Ormond Award for Innovation at RMIT.