Peter Condliffe PhD

Chair, AMDRAS

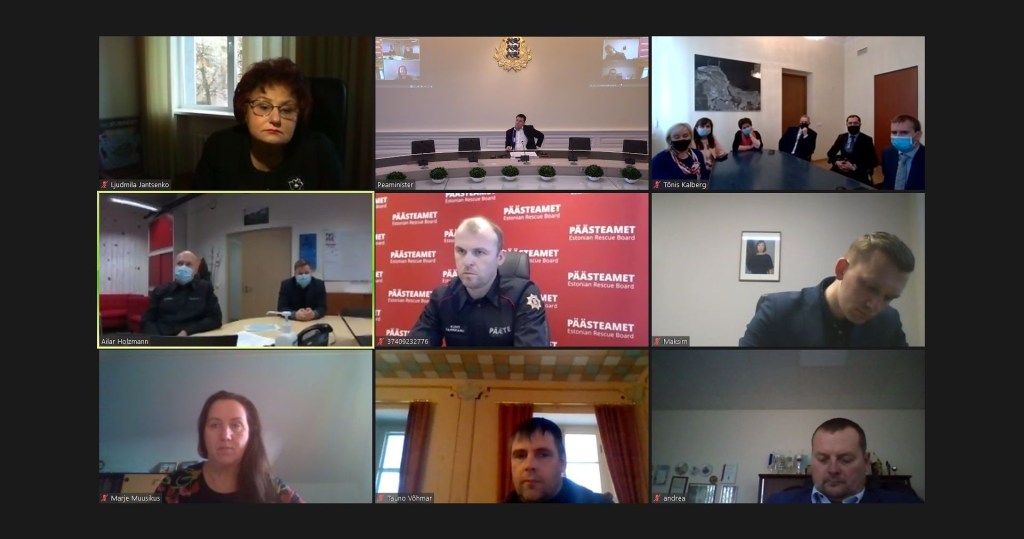

This post is the second in a four-part series as written by Peter Condliffe and based on his presentation in the Australian Dispute Resolution Association ‘International Mediation Conference’ on 15 August 2024 at Sydney.

The Evolution of the Australian Way

The NMAS was a very Australian way of regulating practitioner training, skills development and registration. Since its commencement in 2008 it has, until this recent review, remained virtually static as the mediation field around it has evolved. But even after this review its four central core features of voluntariness and decentralisation, reflexiveness and responsiveness remains.

It relies on voluntary compliance by the accreditation bodies (formerly called Recognised Mediator Accreditation Bodies (RMABs) and now termed Recognised Accreditation Providers) that agree to accredit mediators in accordance with the requisite standard. Involvement in the system is not mandatory and is reliant upon voluntary compliance and membership.

It can be described as an industry based decentralised system where training (both initial and ongoing) as well as registration is conducted by a number of disparate organisations known as Recognised Mediator Accreditation Bodies (RMABs). In many ways it both mirrored and accommodated the Australian federal constitutional system which “spreads” various aspects of governance and administration across multiple representative parliaments and bodies to accommodate the needs of widely disparate but culturally contiguous geographical regions. This decentralized regulatory system is replicated in many parts of the Australian workplace and economy. In part this is a recognition of the vast distances involved but also of the protection of more localised interest groups.

At about the time the NMAS was formed in 2008 Nadja Alexander insightfully described it as a “self-regulatory” approach to regulation embodying reflexive and responsive approaches or theories. These terms she defines as:

“Responsiveness refers to collaboration between government and the group or collective being regulated. Reflexion means that actors have the opportunity to identify issues, reflect upon them and negotiate their own solutions. In their purest form self-regulatory approaches refer to community-based initiatives embracing collaborative, consultative and reflective processes, as distinct from top down policy regulation.”

If one looks at the foundation documents that relate to the formation of the NMAS one can see these core elements being engaged. The role of government seeding grants and reports published by affiliated government bodies associated with a groundswell from industry groups and mediators themselves came together to create the initial framework. It is a regulatory framework that contrasts with more highly centralised regulatory regimes in such disparate places as Hong Kong and Italy (the Hong Kong Mediation Accreditation Association Limited (HKMAAL) and the Italian Ministry of Justice, respectively) which Alexander would probably term a “formal legislative approach”. But it also can be contrasted with more open association market-based systems such as presently operating in the United States of America and the United Kingdom. In many ways it can be seen as a “middling approach” to regulation and compliance.

The provenance of this model went back, at least, to the year 2000 when a government affiliated advisory body known as the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council (NADRAC) launched a discussion paper on “The Development of Standards for ADR” which formed the basis for consultation on this issue. This Report stated that:

“NADRAC proposes a framework for the development of standards for ADR, in which responsibility is shared across service providers, practitioners, and government and non-government organisations (Recommendation 1). It proposes the following strategies:

(i) Facilitate the ongoing development of standards at the sector, program and service provider level, in order to improve the quality of ADR practice and to enhance the credibility and capacity of the ADR field.

(ii) Implement particular standards, within a code of practice, in order to educate and protect consumers, and build consumer confidence in ADR processes.”

One can see in these initial proposals the genesis of the decentralised model. In March 2004, NADRAC released a further paper on mediator accreditation, “Who Says You’re a Mediator? Towards a National System for Accrediting Mediators”. The aim of this paper was to obtain information and to stimulate discussion in the lead‐up to a national workshop on mediation standards. Discussion on it was facilitated at the 7th National Mediation Conference in Darwin on 2 July 2004. With the help of a grant from the federal Attorney-General’s Department the Conference established a broad-based Committee to work on implementation and the establishment of the standards. Notably, for the system’s subsequent development this Committee was representative of the various industry sectors involved, reflected the geographic and disciplinary diversity of practitioners and included members who were suitably experienced in both the practice of mediation and its administration.

At a subsequent conference in 2006 the National Mediation Committee was then formed to attempt to move the proposal forward and to assist to draft standards and a system for mediator accreditation. However, this committee was not able to move the proposal forward and no accreditation system was established at this time. It was not until a further grant was obtained in 2007 by the Western Australian Dispute Resolution Association (WADRA) and a further period of consultation and refinement of the draft Standards made that they were finally operationalized at the beginning of 2008. Professor Tania Sourdin, the academic who conducted this second consultation, recommended and cemented in place the establishment of a voluntary industry system under which organisations that met certain criteria could accredit mediators. This has been a cornerstone of the system ever since. With the help of some more funding the National Mediator Accreditation Committee (NMAC) became the Mediator Standards Board in 2010.

In launching the MSB, his Honor Justice Murray Kellam AO, the then Chairman of NADRAC noted that Australia was the only country to have established a national scheme for mediator standards and accreditation and that the NMAS had ‘prompted the biggest transformation to the professional landscape in the history of mediation in Australia by providing an overarching, base level of accreditation for all mediators irrespective of their field of work.’ Whilst government seeding funds to initiate the NMAS had been obtained it was clear from the onset of these developments that the MSB would need to be wholly funded by RMABs and for practical purposes, by mediators seeking accreditation through RMABs. The MSB passed a significant milestone in 2015 when it successfully concluded a process of consultation and minor revision of the NMAS. The introduction of the new AMDRAS system represents the first significant review of the Standards.

Author Biography

Peter is a Barrister, qualified teacher and mediator. He has also been previously employed in several management and human rights roles including with the United Nations. He is an experienced teacher presenting courses in universities and other organizations. His book “Conflict Management: A Practical Guide” (Lexis Nexis, 2019, 6th Ed.) is well known to many dispute resolution practitioners and negotiators with a 7th edition to be published in 2025. He is Chair of the Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolution Accreditation Standards Board (formerly the Mediator Standards Board) and has served as a Director since 2019 holding positions as Secretary and Convenor of the Research and Review Committees. As well he was the initial drafter of mediation courses for the Dispute Resolution Centres of Victoria; Department of Justice (QLD); the Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators (IAMA – now part of the Resolution Institute) and the Victorian Bar. He is the Principal Instructor in the Victorian Bars’ Lawyers Mediation Certificate which is a specialist course for lawyer mediators. He was the founding President of The Victorian Association for Restorative Justice and is Deputy Chair, ADR Committee of the Victorian Bar, Deputy-President, Council of the Ageing (Vic.), and Member, Senior Rights Victoria Advisory Committee.