Peter Condliffe PhD and Claire Holland PhD

This blog is a summary of a more substantive paper currently in preparation and is based on that paper: See Condliffe, P and Holland C, What Do we Call Ourselves: Conflict Manager or Dispute Resolver, in preparation.

Introduction

This blog has come about as a result of the author’s collaboration on a new and seventh edition of Conflict Management: Theory and Practice (previously titled ‘Conflict Management: A Practical Guide’ Lexis Nexis, 2019). Earlier editions had been written by a single author, and decisions regarding framing, scope, and terminology had therefore not required negotiation. The co-authorship of the new edition thus offered an opportunity to revisit, clarify, and reaffirm the foundational assumptions that have shaped the book since its inception.

Among the most consequential of these framing decisions was the title itself, Conflict Management. Since the publication of the first edition in 1991, this term has been deliberately preferred over the more commonly used ‘disputeresolution’. This choice was not incidental. It reflected an underlying set of conceptual, theoretical, and practical commitments that distinguished the work from other texts in the field and has continued to guide its evolution over subsequent editions. After thorough discussion, the authors reaffirmed their decision to retain Conflict Management in the title, recognising it as central to the book’s epistemological and pedagogical identity.

There are a number of reasons why this may be important because creating “mental models” of our interventions as conflict managers can effect how we behave and make decisions.1 They also help us with longer term, structural and value-based conflict interventions. They can also, we believe, keep us more process oriented and culturally aligned and responsive.

Our discussion unfolded in three ways summarised below.

The Conceptual Conversation

A foundational step was engaging with the concept of conflict management and particularly the term conflict. Although widely used across scholarly and practitioner discourses, conflict remains an inherently complex and contested concept.2 It resists a singular definition and is interpreted variously depending on disciplinary orientation, cultural context, and situational dynamics. In both teaching and professional practice, defining what conflict is, and perhaps more importantly what it means, has proven to be a persistent challenge.3 Increasingly, pedagogical approaches have shifted from prescriptive definitions toward participatory inquiry, encouraging learners and practitioners to articulate, compare, and synthesise their own understandings of conflict.4

We concluded that there were five key interrelated dimensions (perception, interpersonal interaction, interdependence, intrapersonal dynamics, and emotion) which would enable us to provide a conceptual scaffold for understanding these terms. This conceptual argument suggests that conflict is best approached not as a discrete event or condition but as a complex, evolving process embedded in human cognition, emotion, and social relationships. Recognising this multidimensionality provides a conceptual foundation for understanding why management, rather than resolution, may more accurately capture the ongoing, adaptive work required in navigating conflictual human experiences. Our perspective is broadly ‘social constructivist’ in orientation.5

Like Avruch6 and Lederach7 have argued, we believe conflict is both embedded in and expressive of cultural patterns, the shared symbols, narratives, and cognitive schemas that structure how groups perceive and respond to difference. Understanding conflict, therefore, requires a careful examination of the cultural knowledge and everyday assumptions that shape how people interpret social reality.

We were further challenged by the ambiguity and interchangeability of key terms, particularly conflict and dispute. Although frequently used as synonyms in everyday and professional discourse, these terms carry distinct theoretical and practical implications. Conflict can be understood as a dynamic process of disagreement, tension, or grievance that emerges within or between individuals and groups.8 In contrast, a dispute represents a more specific and manifest expression of conflict, such as an event or situation in which opposing parties directly express incompatible or opposing positions or claims.9 In this sense, we consider conflict to be a broader term than dispute.

We were particularly influenced in this respect by the work of Australian diplomat and scholar John Burton, whose pioneering work in conflict analysis continues to influence both international and domestic peace studies. He argued for a sharp distinction between disputes and conflicts.10 According to Burton, “conflicts are struggles between opposing forces, struggles with institutions, that involve inherent human needs in respect of which there can be limited or no compliance.”11 In other words, disputes may be resolved through negotiation or procedural settlement, whereas conflicts reflect structural or identity-based tensions that resist simple resolution because they implicate people’s basic needs for recognition, security, and belonging.12

Whilst we have some issues with Burton’s distinctions it remains conceptually powerful and moving forward from this perspective, the essential task lies not in eliminating conflict but in managing it adaptively and contextually. For us then it is preferable to base the distinction between conflict and dispute on process rather than on the possibility of resolution. A dispute represents a particular response or manifestation within the broader process of conflict, not a fundamentally different phenomenon.

Conceptualising practice as conflict management allows for a more comprehensive engagement with the full range of human experience embedded in conflictual relationships.

The Inclusivity Conversation

The other discussion we had, and are having, arises from our’ extensive practical experience as mediators, trainers, facilitators and mentors. Over many years of practice, the authors have predominantly been supporting individuals and groups in conflict management rather than definitive conflict resolution.

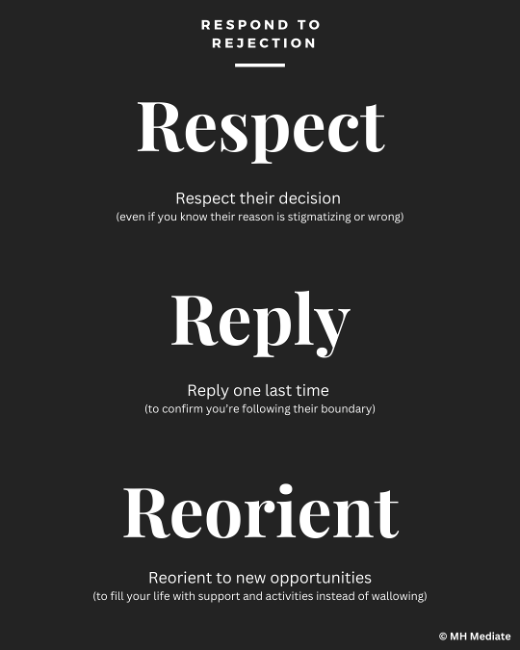

By shifting our focus then to conflict management we recognise that successful practice may involve containment, transformation, or construction of ongoing relational processes, not just the ‘end’ of conflict. This distinction has implications for practitioner identity, process design and expectation-setting for participants.

This inclusive orientation aligns with recent Australian standards and guidelines. For example, the Australian Standards authority’s publication of AS 10002:2022 – Guidelines for complaint management in organisations reflects a shift in terminology from “resolution/resolving” to terms such as “management/managing”, “outcome”, “finalised/ addressed”.13 This shift underscores the importance of process language that accommodates a range of outcomes and recognises the ongoing dynamics of conflicts.

This suggests that organisational, interpersonal or societal conflict may be better framed through inclusive, process-oriented language rather than endpoint-oriented labels. For those managing organisations such as a complex court or legal bodies, this may also be a pertinent issue. We were pleased to see, for instance, in the commercial litigation context, the Honourable Chief Justice of Queensland, Helen Baskill, recently observed, after seeing a recent text by Condliffe that the term “conflict management” rather than “dispute resolution” could have resonance in developing better systemic processes and practices in the court context that she manages.14

From an academic perspective, this inclusivity argument finds support in the literature on conflict management systems and dispute resolution in Australia. Australian scholars have noted the limitations of purely settlement-oriented approaches and the value of conflict management systems that emphasise ongoing dialogue, relational maintenance and the design of integrated conflict management processes.15

The Productive Social Change Conversation

We also considered that, beyond the interpersonal and organisational realms, conflict has a profound relationship with society and social transformation which is important to us as practitioners. As American philosopher John Dewey once said,

Conflict is the gadfly of thought. It stirs us to observation and memory. It instigates us to invention. It shocks us out of sheep-like passivity. Conflict is the sine qua non of reflection and ingenuity.16

From this perspective, conflict does more than disrupt. Conflict can stimulate not only economic and scientific change but also the overthrow of old norms and institutions. It is through contested ideas and practices that norms evolve and institutions adapt.17

This insight aligns us with classical sociological theory.18 According to Coser for example, conflict only becomes dysfunctional within social systems that lack sufficient tolerance for conflict. We also realise that our text owes much in the field of conflict theory to Morton Deutsch, one of the founders of modern conflict management theory, whose modelling emphasized both competitive and cooperative frameworks in conflict.19

Putting this all together we conclude that conflict, when managed constructively, is not just a problem to be avoided but can drive positive social change.

Conclusion

Together, these arguments we believe reasserts conflict management as a more encompassing, process-centred and socially responsive framework for practice. It orients our preference to refer to ourselves as conflict managers rather than dispute resolvers in our professional practices.

Authors Biography

Peter Condliffe PhD is a barrister, teacher and mediator. He has also been previously employed in several academic, management and human rights roles including with the United Nations. He is an experienced teacher having developed and presented courses in universities and other organisations. He is a past chair of The Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolution Standards (AMDRAS) Board and long-serving member of the Victorian Bars’ ADR Committee. He was instrumental in the development of the new national AMDRAS Standards.

Claire Holland PhD is an experienced academic, trainer, mediator and consultant. She has worked nationally and internationally as a mediation and conflict management specialist, and in training and capacity development roles. She has worked in complex and protracted settings on the Thailand Myanmar border and in the Philippines and has carried out consultant-based work in the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. Claire is a trainer and coach mentor with the Conflict Management Academy, specialising in conflict analysis, conflict coaching, leadership and mediation training. Claire is the former Director of the Masters of Conflict Management and Resolution at James Cook University and a founding board member and past Chair of Mediators Beyond Borders Oceania.

- Bartoli A, Nowak A and Bui-Wrzosinska L, ‘Mental Models in the Visualization of Conflict Escalation and Entrapment: Biases and Alternatives’, IACM 24th Annual Conference Paper, 3–6 July 2011, p.3-5, <http://scar.gmu.edu/presentations-proceding/12857> ↩︎

- See generally Peter L Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge (Anchor Books, 1966); Johan Galtung, ‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research’ (1969) 6(3) Journal of Peace Research 167; John Paul Lederach, Preparing for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures (Syracuse University Press, 1995); Morton Deutsch, ‘An Experimental Study of the Effects of Cooperation and Competition upon Group Process’ (1949) 2(3) Human Relations 199; Peter T Coleman, ‘Characteristics of Protracted, Intractable Conflict: Toward the Development of a Metaframework’ (2003) 9(1) Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 1; Daniel Bar-Tal, Intractable Conflicts: Socio-Psychological Foundations and Dynamics (Cambridge University Press, 2013) ↩︎

- Tjosvold, Dean. (2006). Defining Conflict and Making Choices About Its Management: Lighting the Dark Side of Organizational Life. International Journal of Conflict Management. 17. 87-95. 10.1108/10444060610736585. ↩︎

- See for example, Ciobanu (2018), Active and Participatory Teaching Methods. European Journal of Education May August 2018 Volume 1, Issue 2. ↩︎

- See Lederach J, Preaching for Peace: Conflict Transformation Across Cultures, Syracuse University Press, New York, 1995, pp8-10. ↩︎

- Avruch, K. (1998). Culture and conflict resolution. United States Institute of Peace Press. ↩︎

- Lederach, J. P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. United States Institute of Peace Press. ↩︎

- Condliffe and Holland, 2025, s 1.5; Boulle, 2005, p 83. ↩︎

- Moore, C. W. (2014). The mediation process: Practical strategies for resolving conflict (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass. ↩︎

- Burton, J. W. (1996). Conflict resolution: Its language and processes. Scarecrow Press. ↩︎

- Burton, J. W. (1996) f. 28, p 21. ↩︎

- Burton, J. W. (1990). Conflict: Resolution and prevention. Macmillan. ↩︎

- Australian Standard 10002:2022 Guidelines for complaint management in organizations (ISO 10002:2018, NEQ); SOCAP,. Guidelines for Complaint Management in Organisations: Comparison of the 2014 and 2022 Editions, (AS 10002:2022), see https://<www.socap.org.au/public/98/files/SOCAP%20Member_Info_Sheet_2022_LR.p ↩︎

- Article Series: Mediation: Australia’s Place in the International Scene – AMDRAS. ↩︎

- Boulle, L., & Field, R. (2021). Australian dispute resolution: Law and practice. LexisNexis Butterworths; Van Gramberg, B. (2005). Managing workplace conflict: Alternative dispute resolution in Australia. The Federation Press. ↩︎

- Dewey J,Human Nature and Conflict, Modern Library, New York, 1930, p 30. ↩︎

- Deutsch (1973) ↩︎

- Lewis Coser, The Functions of Social Conflict. New York: The Free Press, 1956; Beyond Intractability, Summary of “The Functions of Social Conflict”, <https://www.beyondintractability.org/bksum/coser-functions> accessed 1st November 2025. ↩︎

- Deutsch, M, The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes, Yale University Press, New Haven ↩︎