Dr Claire Holland

Why Mediator Dilemmas Matter

Mediation is often described as structured and principled. An approach that empowers parties to find their own way through conflict with the support of a neutral third party. At its best, mediation provides a space where voice, dignity, and autonomy are protected. Yet, despite this aspirational framing, the reality of practice is rarely straightforward.

Mediators work in rooms populated with human beings whose lives are in flux, often carrying frustration, fear, and a history of fraught relationships. Emotions surge, narratives collide, and the “facts” of the matter are contested, incomplete, or strategically presented. In this unpredictable terrain, ethical dilemmas are inevitable. Should a mediator intervene to balance power? How should they respond when one party is overwhelmed? What if an agreement seems clearly unfair?

Such dilemmas do not have easy answers. They exist in what Donald Schön famously described as the “swampy lowland” of professional practice (1983). Schön’s work on reflective practice provides a powerful frame for understanding the artistry required of mediators. That is, an artistry that blends technique, intuition, ethics, and reflection in order to navigate dilemmas that cannot be resolved through formulaic responses. Lang and Taylor (2000) similarly argue that becoming a skilled mediator is not simply about mastering techniques but about developing reflective capacity. In their text The Making of a Mediator, Lang and Taylor integrate Schön’s reflective practitioner model into the ADR field. Lang in his 2019 text The Guide to Reflective Practice in Conflict Resolution further positions reflective practice as the cornerstone of professional growth in mediation and conflict resolution.

In this blog, I explore how reflective practice helps illuminate the complex ethical landscape of mediation. Drawing on a case study of a residential tenancy bond dispute, I show how reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action enable mediators to navigate dilemmas in the moment and build artistry over time. I then connect these ideas to broader scholarship in Australia and beyond, where the development of mediator artistry has been central to debates about ethics, professionalism, and mediator expertise.

The Reflective Practitioner in the “Swampy Lowland”

Donald Schön’s seminal text The Reflective Practitioner (1983) challenged dominant assumptions about professional knowledge. At the time, technical rationality (the belief that professional competence flowed from the application of scientific theory) was the prevailing model. According to this view, the professional problem was to apply rules, methods, and procedures correctly.

Schön, however, observed that in many domains, including planning, architecture, education, and counselling, practitioners worked not in well-ordered problem spaces but in messy, uncertain contexts. Here, problems were ill-defined, values were contested, and outcomes could not be predicted with precision. These were the “swampy lowlands” of practice (Schön, 1983, p 42).

To navigate this terrain, Schön introduced the concepts of:

- Knowing-in-action: the tacit, often unspoken knowledge that practitioners draw on automatically in the course of doing. Much of what professionals know is embodied and experiential, rather than explicitly codified (p 49).

- Reflection-in-action: reflection that occurs in the moment of practice itself such as a fluid, improvisational interplay between thinking and doing (similar to a jazz musician improvising with other players) (p 54).

- Reflection-on-action: deliberate reflection that occurs after an event, allowing practitioners to make sense of what happened and plan differently for the future (p 61).

Aligning with the views of Lang and Taylor (2000) and Lang (2019), mediators operate squarely in Schön’s swamp. Every mediation involves multiple unknowns: unpredictable dynamics between parties, shifting emotional intensity, cultural nuances, and competing ethical obligations. While codes of conduct provide necessary guidance, they cannot dictate every move. The mediator must learn to improvise by engaging in a “conversation with the situation” (p 79), as Schön put it, where each action invites feedback, and the practitioner adjusts in real time.

A Case Study: Mediator Dilemmas in a Tenancy Bond Dispute

To illustrate, this is an example case drawn from numerous personal experiences in tenancy mediations. These disputes often involve recurring participants, such as property managers representing landlords, who become adept at navigating the process. They sit across from tenants who may be experiencing mediation for the first time, which can create a power imbalance that raises ethical and procedural questions.

The scenario: A tenant, Jacob, seeks the return of his $2,600 bond. Opposite him sits Sarah, a property manager representing the landlord. Sarah is confident, well-prepared, and armed with condition reports, inspection photos, and invoices. Jacob, by contrast, is distressed, under-prepared, and reliant on narrative rather than evidence.

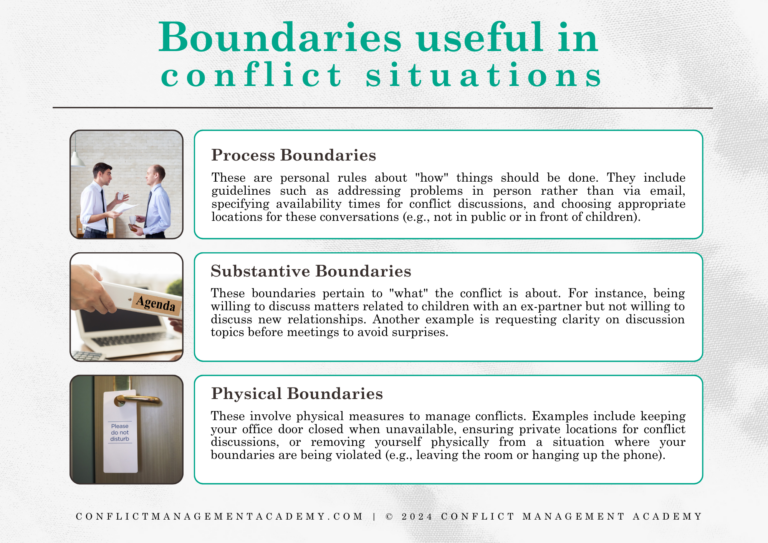

From the outset, a mediator is confronted with dilemmas:

- Power imbalance: How should the mediator address the contrast between Sarah’s professional confidence and Jacob’s emotional vulnerability?

- Procedural fairness: Can a process be “fair” when one party cannot effectively participate? Should the mediator slow the pace, summarise evidence, or even suggest Jacob seek advice, knowing this may frustrate Sarah?

- Knowledge from prior mediations: The mediator recalls that Sarah often claims full invoice amounts despite regulatory provisions that might reduce the actual amount that can be claimed (such as the age of damaged carpet). Is it ethical to draw on that memory in this mediation?

- Advice vs information: In private session, Jacob asks bluntly whether he is “legally entitled” to the bond. Where is the line between providing neutral information and slipping into legal advice?

- Unfair agreement: Jacob ultimately agrees to accept a $300 return, with $2,300 dispersed to the landlord, seemingly out of fatigue and resignation. Should the mediator intervene if the settlement feels unjust?

- Emotional breakdown: After agreement, Jacob breaks down, expressing hopelessness and despair. What is the mediator’s duty of care in relation to his wellbeing?

Each of these dilemmas places the mediator at a crossroads. There is no single “correct” answer. Instead, the mediator must reflect-in-action, balancing ethical obligations, professional role boundaries, and human sensitivity in the moment.

Reflection as Ethical Compass

Why does reflective practice matter here? Because mediation dilemmas are not only practical, they are also ethical. A mediator who blindly follows procedure may preserve neutrality on paper, but fail to achieve fairness in reality. Conversely, a mediator who overcompensates for a vulnerable party may risk undermining the perception of impartiality.

Reflection provides a compass in these grey zones. It allows mediators to:

- Integrate theory and practice: Reflection bridges the gap between principles (such as neutrality and self-determination) and their messy application in practice.

- Maintain ethical awareness: By questioning not only what they do but why, mediators can avoid drifting into unconscious bias or complacency.

- Support emotional regulation: Reflection enables practitioners to notice their own triggers (perhaps frustration at a repeat-user’s tactics, or empathy for a vulnerable party) and to regulate responses appropriately.

- Adapt strategically: Reflection encourages creativity in the moment, enabling mediators to shift structure, language, or process design to re-balance participation.

In short, reflective practice turns ethical dilemmas from paralysing obstacles into opportunities for professional growth and responsive practice.

The Development of Artistry in Mediation

Schön used the term artistry to describe the culmination of reflective practice as the ability to act intuitively, creatively, and ethically in uncertain situations. Artistry goes beyond technical competence. It is not simply knowing the steps of a mediation, but knowing how and when to adapt them.

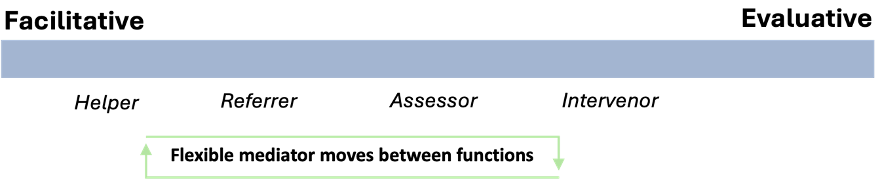

Australian scholarship has made significant contributions to theorising and applying this concept in mediation. The recently revised Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolution Accreditation System (AMDRAS, 2025) explicitly integrates reflective practice, professional judgment, and ethical decision-making into its competency framework, embedding artistry as a national standard. Across the literature, artistry is framed as adaptive expertise and flexible judgment (Spencer, 2024; Spencer & Hardy, 2014; Boulle, 2011), grounded in reflective learning and ethical responsibility (Douglas & Ojelabi, 2023, 2024). Field (2007, 2022) advances this discussion (aligning with Lang, 2019) by emphasising “ethical artistry,” in which mediators combine empathy and neutrality with critical attention to power and justice. Similarly, Douglas and Goodwin (2015) present artistry as a distinctive form of professional competence, where the true effectiveness of a mediator lies not in technical skill alone but in the creative and intuitive responsiveness to the dynamics of a dispute. Hardy (2010) further underscores the role of narrative and emotional competence, highlighting that artistry requires engaging with parties’ stories in ways that acknowledge emotion while fostering constructive reframing. At the same time, Condliffe and Holland (2025, in press) caution that reflective practice has limits, and that real-world, contextual experience is indispensable to developing artistry, a challenge recognised and reinforced in the AMDRAS standards.

Lang (2019) reinforces the idea that reflective practice is not optional, but core to conducting ethical and competent mediation. Lang makes the case that ethical judgement cannot be separated from reflective practice, and that reflection is the key to helping practitioners clarify what values guide them, and how they should act consistently with those values.

Taken together, this body of work positions artistry as a central dimension of mediation practice in Australia, conceptualised as the integration of technical skill, reflective judgment, ethical responsiveness, and creative adaptability.

Reflection-in-Action: Improvisation as Ethical Skill

The tenancy mediation scenario illustrates reflection-in-action vividly. When Jacob becomes increasingly distressed, the mediator must decide: allow him to continue, risking further escalation, or intervene, risking perceived bias. This decision is not made in abstract; it is made in real time, shaped by Jacob’s clenched fists, Sarah’s glazed expression, and the emotional temperature of the room.

Here, reflection-in-action operates like jazz improvisation. The mediator draws on tacit knowledge of communication, body language, and conflict dynamics. They may reframe Jacob’s narrative to bring clarity, pause to re-balance engagement, or shift into private session. Each choice is both action and reflection, and each choice brings new opportunities for feedback that shapes the next move.

This improvisational quality is what makes mediation both challenging and deeply human. As Schön suggested, reflection-in-action is like a conversation with the situation. For mediators, that conversation involves listening not only to words, but to silences, tones, and the subtle cues that indicate when power is tilting or emotions are destabilising the process.

Reflection-on-Action: Building Capacity Through Learning

Equally vital is reflection-on-action. After the mediation, the practitioner can revisit the dilemmas encountered. Did my intervention support or hinder fairness? Did I unconsciously align with one party? Should I have paused the mediation for advice?

Such reflection can occur individually through journaling, or collectively through supervision, peer consultation, or structured professional development. By analysing decisions and their impacts, mediators convert tacit impressions into explicit learning. Over time, this strengthens their capacity for artistry in future cases.

One innovative forum that supports this reflective process is the Conflict Management Academy’s Mediator’s Dilemma series, a monthly seminar inspired by Geoffrey Robertson’s Hypotheticals. Each session presents a fictional yet realistic mediation scenario filled with ethical quandaries, narrative twists, and moments of uncertainty. As the scenario unfolds, participants are invited to step into the mediator’s shoes at critical decision points, debating possible actions, exploring consequences, and engaging with the complexity of real-world dilemmas. The interactive format encourages practitioners to articulate their reasoning, challenge their own assumptions, and learn from the diverse perspectives of colleagues.

For mediators, the series offers a rare and valuable opportunity: a safe space to rehearse responses to high-stakes situations without the pressure of live practice. This collective reflection not only sharpens technical decision-making but also deepens professional artistry by fostering creative, context-sensitive approaches. In this way, the Mediator’s Dilemma Series complements traditional reflective practices (such as journaling and supervision) by embedding reflection-on-action within a dynamic, collaborative community of practice. It transforms abstract ethical challenges into lived, shared experiences, ensuring that mediators refine their judgment, resilience, and artistry for future cases.

The Ethical Heart of Artistry

It is tempting to think of artistry as primarily about skill or style. But artistry in mediation is inseparable from ethics. Each improvisation is bounded by questions of neutrality, fairness, justice, and care.

For instance, consider the final stage of the tenancy case, where Jacob reluctantly agrees to an unfavourable settlement. Technically, party self-determination has been respected. Yet the mediator senses the outcome is more about resignation than genuine agreement. Here, artistry involves discerning how far to probe for informed consent without crossing into advocacy. It is not simply about what works procedurally, but what is ethically sound.

This intertwining of artistry and ethics reflects what Field and Crowe (2020) describe as a contemporary, relational approach to mediation ethics. The authors suggest that rather than relying solely on procedures or rules, effective mediation calls for ethical responsiveness to the unique circumstances of each dispute and the self-determination needs of the parties. Practitioners must combine procedural skill with self-awareness, empathy, and the courage to act in ways that safeguard fairness, even when situations are uncertain or ambiguous. In this view, a mediator’s ethical judgment is not an abstract ideal but a guiding force that shapes their real-time adaptability, allowing them to navigate complex dynamics with both integrity and artistry.

The Mediator as Reflective Artist

Mediators inhabit a professional landscape defined by complexity, ambiguity, and ethical tension. Reflective practice enables mediators to navigate dilemmas ethically, adapt strategically, and cultivate artistry.

The tenancy case illustrates the challenges vividly: power imbalance, vulnerability, unfair settlements, and emotional breakdowns. In such moments, there is no formulaic answer. Instead, the mediator must improvise by thinking and acting simultaneously, guided by reflective awareness.

Over time, these reflective engagements shape artistry. It is constant aim of achieving truly intuitive, responsive, and ethically grounded practice that distinguishes not just competent mediators, but exceptional ones. As the profession continues to evolve, it must guard against overemphasis on procedural compliance at the expense of reflective artistry. For it is in the “swampy lowlands” of practice and amid the human messiness, that the true value of mediation lies.

Reference List

- Boulle, L. (2011) Mediation: Principles, Process, Practice. LexisNexis Butterworths.

- Condliffe, P., & Holland, C. (2025, In Press). Conflict Management: a practical guide, 7th Ed. LexisNexis Butterworths.

- Douglas, K., & Akin Ojelabi, L. (2024). Civil dispute resolution in Australia: A content analysis of the teaching of ADR in the core legal curriculum. Adelaide Law Review, 45(2), 341–370.

- Douglas, K., & Akin Ojelabi, L. (2023). Lawyers’ ethical and practice norms in mediation: Including emotion as part of the Australian guidelines for lawyers in mediation. Legal Ethics. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1460728x.2023.2238281

- Douglas, K., & Goodwin, D. (2015). Artistry in mediator practice: Reflections from mediators. Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal, 26(3), 172–181.

- Field, R. (2022). Australian dispute resolution. LexisNexis Butterworths.

- Field, R., & Crowe, J. (2020). Mediation ethics: From theory to practice. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Field, R. (2007). A Mediation Profession in Australia: An Improved Framework for Mediation Ethics. Australasian Dispute Resolution Journal, 18(3), 178-185.

- Lang, M. D. (2019). The guide to reflective practice in conflict resolution. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lang, M. D., & Taylor, A. (2000). The making of a mediator: Developing artistry in practice. Jossey-Bass.

- Mediator Standards Board. (2025). Australian Mediator and Dispute Resolution Accreditation System (AMDRAS) standards. Mediator Standards Board. https://msb.org.au

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Spencer, D. (2024). Principles of dispute resolution (4th ed.). Thomson Reuters.

- Spencer, D., & Hardy, S. (2014). Dispute resolution in Australia: Cases, commentary and materials. Thomson Reuters.