[Free Image by Augusto Ordonez, Pixabay]

On 10 April 2019, Judge Dowdy of the Federal Circuit Court published his reasons for refusing to make a consent order that an employment law matter be referred to mediation by a Judge.

The parties in Wardman & Ors v Macquarie Bank Ltd [2019] FCCA 939 applied for consent orders to resolve some procedural matters and refer the substantive dispute to mediation by a Judge, pursuant to s 34 of the Federal Circuit Court Act 1999 (Cth) and rule 45.13B of the Federal Circuit Court of Australia Rules 2001 (Cth). Rule 45.13B(2)(a) explicitly anticipates that an order referring a proceeding to mediation may order that the mediator appointed be a Judge:

…(2) The mediator for the mediation must be: (a) a Judge; or…

Nonetheless, Dowdy J contacted the parties informing them that he believed he should not make an order that a Judge act as a mediator. Instead, he made an order for a Registrar to act as mediator. His Honour’s reasoning for his refusal to appoint a Judge as mediator can be summarised by the following 3 propositions:

- Mediators and Judges perform distinct roles

- Acting as a mediator is incompatible with the Constitutional role of a Judge (and Rule 45.13B(2)(a) is invalid)*

- Judges are not qualified to act as mediators

1. Mediators and Judges perform distinct roles

Source of authority

- The Constitutional power to mediate is the Conciliation power in s 51(xxxv).

- A Judge exercises judicial power under s 71 of the Constitution.

Facilitation of consensus v determination of dispute

- Mediators aim to resolve disputes by consensus.

- Judicial power is an elusive concept, but at its core is the power to decide controversies (ie, to determine the outcome of disputes).

Context of decision-making

- Mediation is typically private, confidential, informal and non-adversarial.

- Judicial power must be administered in public and reasoning must be published. The judicial process is primarily adversarial.

2. Acting as a mediator is incompatible with the Constitutional role of a Judge

Judicial power must be exercised according to judicial process

- Judicial process requires (with limited exceptions) open and public inquiry, application of rules of natural justice, identification of law and facts, and application of law and facts to decide the outcome (see Grollo v Palmer).

- Mediators meet in private, sometimes with only one party at a time, do not decide facts or law, do not make decisions, mediated decisions are not required to be made according to legal principles, and neither reasons nor decisions are published.

Judges cannot perform functions incompatible with judicial power

- Judges cannot exercise non-judicial functions that would prejudice their capacity to discharge effectively the judicial powers of the Commonwealth

- Rule 45.13B should be read to preclude a Judge who has presided over a mediation from subsequently hearing or determining the case.

[31] If I had acted as a mediator in this case as requested by the parties I would have sterilised and rendered inoperable my judicial power to hear and determine the case. In other words, by agreeing to act as a mediator I would have undertaken a function which was incompatible with, and which would have precluded me from, discharging my obligation as a Judge to hear and determine a matter which in the regular course had be docketed to me by the registry of the Court.

Courts and Judges cannot and do not provide advisory opinions

- Judge Dowdy referred to Plaintiff M68/2015 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection as authority for the proposition that Chapter III Courts and Judges cannot provide advisory opinions.

- Mediators in court-connected mediations “invariably” provide advisory opinions.

[32]…parties to a mediation invariably expect the mediator to give his or her views on their respective prospects in the context of the existing or foreshadowed litigation which the mediation is seeking to obviate and on the reasonableness of any proposed settlement. This is the case whatever the kind or model of mediation being undertaken. It is particularly the case that economically weaker and more vulnerable parties desire the opinion of the mediator on such matters.

Mediation is not a traditional function of courts

- Some functions other than the adjudication of rights were traditionally exercised by courts and therefore fell within the concept of judicial power contemplated by the authors of the Constitution. For example, administration of trust assets, winding up companies, maintenance and guardianship of infants, grants of probate, and making of rules of court.

- The process of mediation cannot be accepted to have been a traditional or historical feature of the powers exercised by courts.

Mediation functions are distinct from judicial power

- This proposition was confirmed by the Boilermakers case – a power to prevent and settle disputes by conciliation and arbitration is completely outside the realm of judicial power.

- Although mediators and Judges both practise fairness, patience, courtesy and procedural fairness, only a Judge determines a justiciable issue.

- Because the power to mediate falls outside judicial power, Dowdy J concluded that:

[38]…neither Parliament nor the Judges of this Court can make rules of court that authorise or require a Judge of this Court to act as a mediator

- While Courts and Judges regularly encourage settlement and adjourn hearings to allow settlement negotiations to occur, it is not considered appropriate for Judges to participate in those negotiations themselves.

- There is no inherent connection between mediation, conciliation and legal proceedings, as not all mediators are legally trained and not all mediations occur in connection with litigation.

- Mediation is not incidental to the exercise of judicial power.

3. Judges are not qualified to act as mediators

- Mediation is a craft that requires specific education and training, as well as accreditation and ongoing professional development.

- Eminence, judicial ability and legal knowledge and experience do not necessarily equip Judges to act as a mediator.

- Judicial Registrars of the Federal Circuit Court are trained and accredited mediators.

- There are thousands of appropriately qualified and accredited mediators who could conduct private mediation at an affordable cost.

- It is inappropriate to appoint a Judge to mediate a case merely to access the authority of the Judge to induce or extract a settlement.

- Judges should give exclusive primacy to their judicial role rather than acting as a mediator in cases before the Court.

- Judges have busy dockets and it is unjustifiable to take time out of the activity of judging in order to act as a mediator.

- Judges should not risk being called as witnesses about what happened in private mediations.

- If a Judge acting as a mediator gave an evaluation of the legal case, and a Judge acting as a Judge subsequently decided differently, the standing of Courts and Judges would be diminished.

Comment

This judgment provides some very interesting insights about court-connected dispute resolution practice. Dowdy J has lived experience as a senior legal practitioner with many years’ participation in court-connected mediation and some of his reasoning is based upon that personal knowledge. In paragraph [32] quoted above, His Honour claimed that mediating parties, particularly weaker or more vulnerable parties, invariably expect the mediator to express views about both the likely outcome of litigation and whether or not a proposed settlement is reasonable. His Honour continued:

[33] It so happens that, in the course of my practice as Counsel over the 25 years prior to my appointment to this Court I appeared at well over 125 mediations, regularly before the pioneers of mediation in Australia, being Sir Laurence Street QC and Mr Trevor Morning QC. In my experience virtually all mediators are prepared at a mediation over which they preside to advise in general terms, both on the parties’ respective prospects of success in any litigation and the reasonableness of the proposed settlement terms. Some very few mediators may decline to give their views on prospects of success, but I have never known or heard of a mediator failing to give, either expressly or at the very least impliedly, his or her approval and approbation to the settlement which successfully concludes the relevant mediation.

His Honour returned to his strong view about what litigating parties expect from a mediator:

[55]…by not evaluating the parties’ prospects of success I would have denied to them a characteristic function expected of mediators (see [32] and [33] above) which would be provided by Judicial Registrars and private mediators.

The mediations described fall far outside the concept of facilitative mediation. If evaluation is a “characteristic function” of court-connected mediation, then this should be acknowledged properly and taken into more serious consideration in training and accreditation processes. The question of whether or not litigating parties expect this style of mediation (a) because it is what they have experienced before, or (b) because it is their preference over other styles, is also worthy of interrogation. Should facilitative mediators market their services from a point of difference, instead of assuming that facilitation is understood by prospective clients as the “standard” form of mediation?

The equating of mediation with conciliation in the judgment was the means by which His Honour located the mediation function within the Constitutional powers. The definition of mediation is hotly disputed within the dispute resolution community (as is whether Dispute Resolution is preferable to Alternative Dispute Resolution). However, this judgment raises again the question of whether or not court-connected dispute resolution of the character described and expected should more appropriately be called “conciliation”, in order for it to be distinguished from other kinds of dispute resolution practice.

There is great potential for the private mediation sector to provide affordable dispute resolution services to litigants. Judge Dowdy identified many problems with using Judges to mediate, when there is a surplus of appropriately qualified and accredited practitioners available to assist parties navigate a path to settlement. What creative ways can the mediation profession use to attract the respect and legitimacy that parties are seeking when they prefer senior legal minds to act as mediators of their disputes?

*Note: The decision specifically relates to Judges who exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth of Australia. The Commonwealth Constitution mandates separation of judicial power and the Commonwealth legislature cannot confer non-judicial functions on Judges except those that are incidental to their judicial function (see Boilermaker‘s case). The situation is different in state jurisdictions (see Kable and Momcilovic cases).

The ethics of 21st century ‘family justice’ research, and its application to professional practice

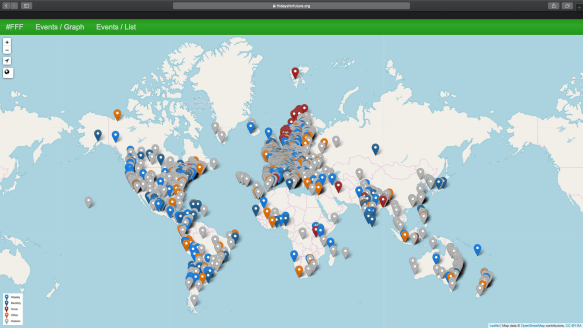

The ethics of 21st century ‘family justice’ research, and its application to professional practice School students are protesting today about the failure of politicians to take serious action in response to climate change. They are calling for action. The

School students are protesting today about the failure of politicians to take serious action in response to climate change. They are calling for action. The

This post was written by Pauline Roach and is part of our series of summaries of works in progress presented at the 6th ADRRN Roundtable held in Dunedin in December 2017. Pauline was involved closely in the development and implementation of the system at the Roads and Maritime Services of New South Wales described here.

This post was written by Pauline Roach and is part of our series of summaries of works in progress presented at the 6th ADRRN Roundtable held in Dunedin in December 2017. Pauline was involved closely in the development and implementation of the system at the Roads and Maritime Services of New South Wales described here.