Samantha Hardy

This article has been republished with permission. The original publication can be found at The Conflict Management Academy.

In my work with clients in conflict, I constantly find that they have missed many opportunities to manage conflict more effectively. In particular, they often fail to set appropriate boundaries (or ANY boundaries) to allow themselves to be at their best in conflict situations.

Boundaries are a fundamental part of preventing unnecessary conflict, and managing conflict effectively when it does arise. Once you identify which kinds of boundaries work best for you, they are easy to set and maintain. You will start to become more courageous in conflict, bet better outcomes, and keep your integrity intact.

Caution

In any conflict situation, there are risks as well as opportunities. The information provided in this article includes general suggestions that are useful in many conflict situations. However, there are certain types of conflict, particularly when someone is using coercive or controlling behaviour over another person, in which boundaries are unlikely to work. Please think carefully before implementing any of the suggestions in this article, and ensure that you do not put yourself or others in danger. If in doubt, seek professional support, from a counsellor, a therapist or even the police if the risk of harm is imminent.

What are boundaries?

Boundaries are basically our own personal rules about what is, and what is not, okay. Effective boundaries support us to behave at our best in difficult situations. Brené Brown explains that boundaries help us to find ways to be generous to others, while still behaving in a way that is consistent with our personal values.

In conflict, boundaries allow us to engage in constructive conflict management, instead of simply avoiding the conflict or lashing out in order to protect ourselves. They provide a structure for communicating effectively in difficult situations.

If you don’t set good boundaries in conflict situations, you will end up feeling resentment, anger and frustration. You will act in ways that you later regret. You will damage relationships and your own reputation. You will not get what you need, you will not say what you need to say, and you will say things that you later wish you hadn’t said.

With good boundaries

- You will prevent unnecessary conflict.

- You will be able to stand up for yourself in conflict, while maintaining your integrity.

- You will be able to communicate better in conflict situations.

- You will be more understanding towards those with whom you are in conflict.

- You will manage your emotions better in conflict interactions.

Types of boundaries

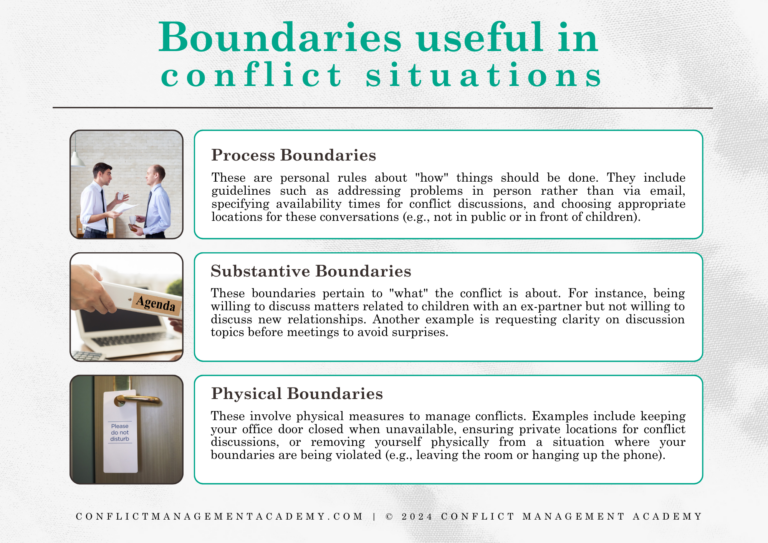

There are different kinds of boundaries that are useful for different situations. In conflict, there are three main types of boundaries: process boundaries, substantive boundaries and physical boundaries. These can all be used to prevent unnecessary conflict or to support you to manage conflict that does arrive courageously and with integrity.

A process boundary is a personal rule about “how” things should be done. For example, you may say to your employees that if they have a problem with something that you do at work, they should come and speak to you about it in person, rather than complaining behind your back or sending an email. Other process boundaries might relate to time – when you are and are not available to talk about a conflict, and for how long. Process boundaries may also relate to where conflict conversations take place (e.g. not in a public place, or not in front of children).

A substantive boundary relates to “what” the conflict is about. You may, for example, set a boundary that you are willing to talk to your ex-partner about what is best for the kids, but you are not willing to talk about your new relationship. A substantive boundary might be asking someone to be very clear about what they want to talk with you about before a meeting, so that you can be prepared to discuss those particular issues without being taken by surprise.

Physical boundaries are very useful in conflict situations. They may include things like keeping your office door closed when you are not available to have a conversation; ensuring that conflict discussions take place in a location where nobody can overhear what people are saying; or you physically removing yourself from a conversation in which someone is breaching your other boundaries (e.g. by walking out of the room, or hanging up the phone).

How to set boundaries

In order to set good boundaries, we need to know what is important to us. Our boundaries should support us to act in accordance with our values. We also need to know what kinds of behaviours from others make it difficult for us to maintain our integrity in conflict situations, and what kind of actions support us to communicate effectively. We need to distinguish between things that make us feel safe, but prevent us from managing conflict effectively (e.g. avoiding the other person) and things that enable us to interact in a constructive way.

Try to think about preventative boundaries, as well as boundaries that you might be able to use in the moment during a conflict conversation.

Things to think about when setting boundaries in conflict situations:

- Which of our values are most important to us in conflict situations?

- What kind of behaviour would be consistent with our values?

- What would we like others to do in conflict situations to enable us to manage the conflict constructively?

- What would help us to communicate effectively in conflict situations, so that we can listen respectfully but also say what we need to say?

- What makes you uncomfortable or stressed in conflict situations?

- What helps you communicate effectively in conflict situations?

- What process boundaries would support you in conflict situations?

- What substantive boundaries would support you in conflict situations?

- What physical boundaries would support you in conflict situations?

It can be difficult to get started and learn how to set effective boundaries in conflict situations, but fortunately The Conflict Management Academy provides an online module so you can develop the skills to interact with courage!