Dr Rachael Blakey

For several decades, the Australian family dispute resolution literature has examined the operation of family mediation and other family dispute resolution procedures. Much of this data comes from funded evaluations and projects following the Family Law Amendment (Shared Parental Responsibilities) Act 2006. However, the English and Welsh literature on contemporary family mediation is limited in comparison. Much of our research has remained focused on the court system, even though many, if not most, people involved in child arrangements or post-separation financial matters deal with their disputes outside of it. My monograph, Rethinking Family Mediation: The Role of the Mediator in Contemporary Times, seeks to reinvigorate discourse and debate on family mediator practice within not only England and Wales, but also other jurisdictions, including Australia. Its opening paragraph reads:

‘Family mediation, like many other procedures, is in a transitionary period. Several traditional concepts – neutrality, facilitation and non-legal support – continue to dominate the discussions around the role of family mediation and the family mediator. These notions remain fundamental to family mediator practice, though their hold has weakened over time. Following decades of reform to the family justice landscape, the work of family mediators is now underpinned by a number of other concepts: flexibility, evaluation and, sometimes, quasi-legal oversight. Family mediators continue to perform their traditional functions, but balance them alongside a rising demand to adapt. They follow a flexible conceptualization in order to provide more comprehensive support to their clients, many of whom have limited access to legal or other advice in the early 21st century.’ (Blakey 2025, p. 1)

Today’s English and Welsh family justice system is very different to that in Australia. We do not have any triage system like the Child and Family Hubs, nor is family dispute resolution mandated. In fact, the Ministry of Justice recently backtracked from 2023 proposals to require most private family law disputants to demonstrate a ‘reasonable attempt to mediate’ before initiating court proceedings, citing concerns about the use of family mediation in cases of domestic abuse. Interestingly, amendments to our Family Procedure Rules in April 2024 mean that judges now have more power to adjourn court proceedings to encourage the use of ‘non-court dispute resolution’ (including family mediation). Judges can also impose a cost order on parties who do not attend a non-court dispute resolution process ‘without good reason’. Whether the Family Procedure Rules have led to non-court dispute resolution becoming mandatory has yet to be seen. Regardless, Rethinking Family Mediation offers valuable insights for family dispute resolution practitioners and academics in various other jurisdictions. It illustrates how policy and legislation can shape mediator practice over time, highlighting mediation’s central positioning within the broader family justice system.

Uncovering the transition from limited to flexible mediator practice

The key thesis underpinning Rethinking Family Mediation is that the role of the family mediator (particularly in England and Wales) has broadened over time, and it is the lack of recognition that this development has occurred, not the development itself, that is inherently problematic. More specifically, I argue that there has been a transition from a limited mediator archetype to a flexible mediator archetype.

The limited mediator archetype is how family mediation practice was, and typically continues to be, conceptualised. They are facilitative and strictly neutral, ensuring that decision-making power rests with the parties at all times. This limited archetype was logical in the traditional English and Welsh family justice system when funding was accessible for many separating parties. Many individuals could still afford a lawyer, even if they were not eligible for legal aid. The limited mediator’s strictly facilitative role was thus appropriate, as more evaluative support and guidance was provided by a lawyer (or other legal practitioner) (figure 1). Nonetheless, the monograph uncovers a long-standing neutrality dilemma for family mediators: neutrality prohibits them from reacting to a power imbalance, yet, in many instances, to do nothing is also an unneutral act. This paradox suggests that the limited mediator was never a perfect or perhaps even ideal archetype.

Figure 1: A binary understanding of facilitative and evaluative behaviours

This critique holds even more weight today. The family justice system in England and Wales is drastically different to when family mediation was first piloted in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Over several decades, policy has increasingly presented mediation as the norm, not simply an alternative, for family matters. This push for private ordering accumulated in the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) which, as of April 2013, removed legal aid for the majority of private family law court proceedings. At the same time, traditional legal support has become increasingly inaccessible for most separating families. Both factors have led family mediation’s clientele to diversify, with many cases now involving complex legal disputes or difficult party dynamics. The limited mediator, who is unable to provide any form of evaluation, is poorly suited to this clientele. Calls for mediators to adapt have increased as a result.

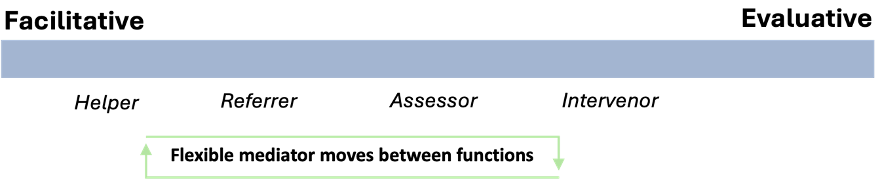

The monograph argues that mediators have transitioned to a flexible archetype over several decades. It recognises that the demand – both within policy and academic scholarship – for mediators to do more is, in fact, a call for mediators to become more evaluative. The flexible mediator archetype continues to perform a facilitative role, but evaluation is woven within their practices. Facilitation and evaluation are thus not a binary distinction, but rather two concepts on a continuum of mediator practice (as originally proposed by Riskin in 1996, though much of the contemporary English and Welsh literature on family mediation does not acknowledge his work). Mediator neutrality is subsequently re-understood as a moderate concept that does not need to be strictly upheld when doing so would compromise fairness or another normative concept. My monograph recognises that the flexible mediator archetype operated prior to the LASPO reforms, with a number of earlier studies demonstrating the varied work of mediators. However, it is submitted that the contemporary family justice landscape necessitates the archetype even further.

Revealing the flexible mediator archetype after the LASPO reforms

In England and Wales, and many other jurisdictions, debates around how to reform family mediation often become circular. It is said that change is needed to provide a better service. However, such change is not possible under the traditional conceptualisation of the (limited) family mediator. Rethinking Family Mediation submits that this stagnancy is resolved if the flexible mediator archetype is explicitly recognised.

To inform debate, the book outlines findings from an empirical project, consisting of a content analysis of family mediation Codes of Practice and semi-structured interviews with 17 family mediators. Its empirical findings first reveal a new theoretical framework of four mediation functions, all of which are recognised and adopted by both family mediators and their regulatory bodies (figure 2). Mediators are primarily helpers, but regularly evaluate the proposed settlement or party dynamic to determine if they should become referrers to another service (notably legal advice). Mediator evaluation becomes significantly more prominent as they become assessors and, furthermore, intervenors. Additional interview data shows that mediators feel that they are responsible for responding to difficult party dynamics and unfair settlements, justifying their more evaluative practices. Of particular note within the empirical data is the mediator sample’s regular reference to legal rules, set out in both legislation and case precedent. This alludes to a growing quasi-legal role for today’s family mediators, most likely influenced by the withdrawal of accessible legal support after the LASPO reforms.

Figure 2: The mediator function framework, plotted on a continuum of facilitative to evaluative strategies

These more evaluative behaviours are discussed by the entire mediator sample, even if a participant understands their neutrality in very strict, absolute terms. Intriguingly, over two-fifths of the mediator sample prefer an alternative understanding of their neutrality that enables them to intervene in negotiations to encourage a good quality settlement. This stance appears more closely aligned with the concept of impartiality, rather than neutrality, though whether the former is a better term to describe the flexible mediator archetype is unclear (mirroring similar debates in Australia).

Implications for family justice going forward

The quasi-legal role of flexible mediators, as identified through the monograph’s empirical data, has significant implications for the professionalism and training of the profession. One chapter of Rethinking Family Mediation specifically considers the extrinsic and organisational barriers to reform, asking whether family mediation should be regarded as a ‘legal service’ under English and Welsh legislation. While the monograph does not provide a definitive answer to the question, it hopes to reinvigorate debate in the area. The chapter also uncovers findings on the current status of family mediation services at a time when the government expects parties to mediate but has provided very little government funding to support mediators themselves.

Importantly, the findings covered in this book have significant implications for our understanding of family justice. Family justice is generally understood as something that is only available through court (and supported by legal representation). Yet much of the empirical data discussed in the book is evidence of a shift in not only family mediator practice, but family justice itself. In the contemporary English and Welsh, as well as Australian, landscape, family justice is increasingly provided through non-lawyers, such as mediators, who are often informed by legal norms. The book connects these changes to a rising hybridity across family law practice, with lawyers additionally becoming more collaborative and less adversarial over time.

This contemporary vision of family justice is not ideal, nor perfect. Without further scrutiny of the various professionals within the family justice system, the risk of improper or unfair outcomes increases. However, Rethinking Family Mediation is premised on finding pragmatic solutions to the challenges within our modern family justice systems. In order to do so, the reality of non-dispute resolution practice must be identified and, importantly, recognised.

It is of no surprise that the monograph regularly returns to the concealment of the flexible mediator archetype – and most likely many other flexible practitioners – as a key issue within our current discourse around family justice reform. Ultimately, it argues that the changes in family mediator practice have been both a natural part of the profession’s development, as well as a consequence of the contemporary family justice system with limited funding and inaccessible legal support. The book will therefore be of significant interest to anyone interested in learning more about family dispute resolution in terms of not simply how the process was traditionally conceived, but how it operates in reality.

Author Biography

Dr Rachael Blakey is an Associate Professor at the University of Warwick. Her research focuses on family mediation and access to justice. She is a co-opted Director of the Family Mediation Council, the main regulatory body for family mediators in England and Wales. Rachael is interested in legal professionalism more widely, and is currently conducting the first empirical study on the English and Welsh ‘one-lawyer-two-clients’ format of family law support.

Author details: rachael.blakey@warwick.ac.uk | University Profile | LinkedIn | Rethinking Family Mediation: The Role of The Family Mediator in Contemporary Times (Bristol University Press 2025)

All figures were provided with permission from Bristol University Press.