By Shanza Shafeek

This is the first blog post in a series written by undergraduate law students enrolled in Monash University’s Non-Adversarial Justice unit in 2024. The very best posts have been published here.

Family disputes are inherently stressful, but for those who have experienced trauma—especially from domestic and family violence—the process can be even more overwhelming.

While the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) promotes Family Dispute Resolution (FDR) as a flexible, less adversarial alternative to litigation, it often fails to adequately address the unique needs of trauma survivors. This highlights the urgent need for a trauma-informed FDR service that supports victims while promoting healing.

In this blog post, we will explore the concept of FDR, the importance of a trauma-informed approach, the key elements that make it effective, the challenges it presents, and how these elements contribute to a more empathetic, supportive process.

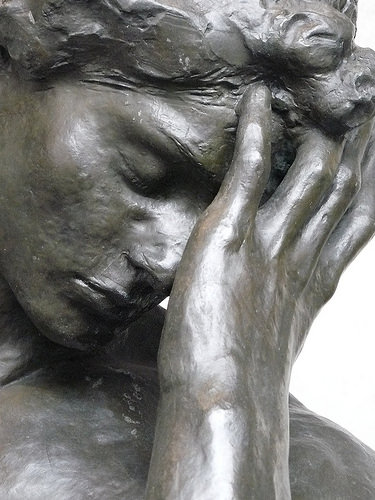

- Sofia von Humboldt CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

What is Family Dispute Resolution?

FDR is a process where an accredited Family Dispute Resolution Practitioner (‘FDRP’) helps families resolve disputes related to separation or divorce outside of court.

The FDRP assists in creating parenting plans that outline future arrangements based on the best interests of the children. The goal is to resolve issues through ‘genuine effort’before resorting to court orders, promoting ‘cooperative parenting’.

Mandatory FDR requirements include exemptions for cases involving child abuse, family violence, urgency, or an inability to participate, ensuring that FDR is only used when appropriate.

The Need for a Trauma-Informed FDR Service

Trauma-informed care recognises the profound impact trauma has on individuals and strives to create a safe, supportive environment for survivors. Despite some exemptions, around 41% of family violence victims still use FDR to address their needs. However, the adversarial nature of disputes, the presence of perpetrators, and the language used in FDR can trigger past trauma, making the process harmful for victims.

Philippa Davis from the Women’s Legal Service emphasises the importance of having ‘safe processes’ for family violence survivors. Around 23% of victims report feelings of fear and power imbalances during FDR, which often leads to pressure to accept unsafe and undesired agreements. A trauma-informed FDR service, on the other hand, facilitates safer participation, enhances communication, and increases the likelihood of reaching mutually satisfactory agreements.

For example, Rachael Field and Angela Lynch introduced the ‘Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution’ (CFDR) model in 2009—a trauma-informed, four-phase framework. Piloted in five Australian locations, this model was evaluated as ‘holistic and safe’ for victims, demonstrating the positive impact of trauma-informed practices in FDR.

Elements of a Trauma-Informed FDR Service

A trauma-informed FDR service must integrate six key elements to address trauma.

- Before the Session:

Assessments:

A trauma-informed FDR service must start with comprehensive suitability and risk assessments to ensure the process is both safe and supportive for victims. These assessments should evaluate critical factors such as violence, power imbalances, and the psychological well-being of participants to determine whether FDR is suitable.

FDRPs should be trained to conduct trauma assessments effectively in cases involving trauma. Studies show that around 30% of parents feel FDRPs lack the necessary expertise to address abuse, highlighting a significant gap in knowledge. This points to an urgent need for targeted training in trauma-informed practices, including safety planning and psychological first aid, so FDRPs can perform these assessments effectively.

Cultural competence is also a key component of these assessments, especially when working with diverse trauma survivors. Susan Armstrong emphasises that FDRPs have reported ‘less confidence’ in cultural competence, indicating the need for cultural training (including First Nations traditions) to ensure parties feel understood, respected and supported from the outset.

Once FDR is deemed suitable, practitioners and domestic violence workers should adopt a ‘multidisciplinary’ approach to develop risk management plans that address the specific trauma needs identified during assessments. Andrew Bickerdike highlights that these plans may include measures such as separate waiting areas and virtual FDR options to create a more supportive environment for victims.

Information:

Clear and comprehensive information must be provided to participants before FDR sessions. As Joanne Law highlights, this information should include details on participation requirements, the roles of FDRPs and lawyers, any necessary religious or cultural accommodations, and the availability of breaks.

Participants should also be informed of their right to have a support person, their ability to express discomfort or withdraw from the process, and the trauma-informed practices in place, such as promoting autonomy and empowerment. Eugene Opperman emphasises that providing this information helps alleviate pre-session anxiety, as it ensures participants are fully aware of their rights and the measures in place to safeguard their well-being.

- During the Session:

Safe Participation

During the sessions, it is crucial to create a safe environment that encourages active participation. A ‘co-mediation approach’ as suggested by Field and Lynch for the CFDR model, can be particularly effective. This approach involves using gender-balanced mediators and legal advocates for both parties to prevent ‘gender bias’– an issue highlighted in the Post-2006 Evaluation Report.

FDRPs must cultivate a welcoming atmosphere using calming language, offering private rooms to ensure confidentiality, and ‘giving ample time for each party to speak’—strategies emphasised by Dee Hardy. Such an environment helps parties make decisions that align with their own interests and the best interests of their children, rather than feeling pressured into ‘unfavourable choices’, which has been a noted concern.

Corinne Henderson and Isobel Everett further recommend minimising staffing changes, offering a variety of choices, and avoiding arbitrary rules to ensure consistent participation. These elements enhance trauma-management and foster open communication, ultimately making the process more effective for everyone involved.

Validation:

Validation is a crucial component of a trauma-informed FDR service. FDRPs should actively listen to participants, ask trauma-sensitive questions like “How did that make you feel?” and express genuine empathy. These actions help bolster participants’ self-worth and support their emotional well-being, addressing the high levels of acrimony and self-doubt reported by 17% of parties in family disputes.

FDRPs should also remain attuned to participants’ emotional states throughout the session. The concept of the ‘window of tolerance,’ as described by Pat Ogden, Clare Pain and Janina Fisher, is particularly useful. This framework helps FDRPs recognise when a participant is approaching the limits of their emotional regulation—whether in a state of hyperarousal (anxiety) or hypo-arousal (shutdown).

By adjusting the process to stay within the participant’s ‘their ‘optimal state of balance’, FDRPs create a supportive and constructive environment.

- After the Session:

Summaries:

After each session, FDRPs should provide a clear summary of the outcomes and outline the next steps to ensure that all parties understand the progress made, helping to alleviate anxiety.

Conducting a debriefing immediately after the session allows participants to reflect on their experiences, validate their emotions, and address any lingering concerns. By actively involving them in determining the next steps, this trauma-informed approach enhances their sense of control and supports their healing.

Follow-Ups:

Follow-ups are essential for providing ongoing support and ensuring the long-term effectiveness of agreements. Around 19% of parents who reach an FDR agreement no longer have one a year later. To address this, a follow-up within 1-3 months should assess the agreement’s effectiveness and evaluate parties’ evolving needs. Itshould also include a specialist risk assessment for any new concerns and seek feedback on the trauma-informed FDR service.

A second follow-up, 6-12 months later, should focus on the long-term impact of the mediation, review any additional support needs (such as counselling), and explore the possibility of further mediation. Similar to the CFDR approach, this continued access to resources ensures that parties receive sustained support throughout their healing journey.

Challenges:

Designing a trauma-informed FDR service comes with its challenges. The AIFS evaluation of CFDR found that “some parents still experienced considerable emotional difficulty, even trauma, in mediation,” highlighting the ongoing challenge of effectively addressing trauma within FDR processes.

Additionally, Field and Lynch point out that trauma can significantly impair communication skills, suggesting that specialised training in ‘communication’ and negotiation strategies is essential for trauma-informed FDR services—though such training can be costly.

A trauma-informed FDR service also requires substantial resources, including ongoing, high-quality training for FDRPs and regular evaluations. These challenges must be carefully managed to ensure that trauma-informed FDR services are effective and sustainable.

- CathrineSæther CC BY-SA 2.0

A trauma-informed FDR service is crucial to effectively support trauma survivors. By integrating the six core elements, FDR can foster healing and achieve outcomes that the adversarial system often fails to provide. As our understanding of trauma continues to grow, FDR services must evolve to offer the compassionate care that victims truly need.

ChatGPT use:

This blog post was developed with the assistance of ChatGPT to identify key issues, which were subsequently fact-checked and supported with relevant journal articles. The insights provided by ChatGPT helped shape the initial framework, ensuring a comprehensive exploration of the topic.

About the author:

My name is Shanza Shafeek, and I am a fourth-year Law/Arts student at Monash University, specialising in sociology. I am currently working as a paralegal in institutional abuse and as a marketing team member for the Muslim Legal Network. I have also been actively involved as a Monash Law Ambassador and a Human Rights Project member for Amnesty International. I am passionate about legal policy, family law, and promoting culturally responsive approaches within legal practice to support diverse communities. I can be found on Linked In.