By Joana Bourouphael

This post is written by Joana Bourouphael, a student who studied Non-Adversarial Justice at the Faculty of Law at Monash University in 2016. Joana was part of the unique placement program for that unit, an example of Work Integrated Learning. In the program, students spend 3-5 days at an organisation experiencing both adversarial and ‘non-adversarial’ practices. Students are then expected to produce a written assignment that addresses both practical and theoretical insights into an issue relating to non-adversarial justice. This post demonstrates how direct experience of legal processes enriches the learning experiences of participating students.

This post has been written in response to a placement I completed where I shadowed a barrister in a murder trial. The majority of my observances surrounded witness examination. The post begins with a brief description of my experience of the adversary system and what I was able to witness. This is followed by an introduction to the adversary system in Australia and the features of it that are relevant for my critique. Some problems of the adversary system are then highlighted before proposals for reform are suggested.

1. MY OWN “WAR STORY”

The first time I stepped into the courtroom, I believe I had done so with an open mind. I had been sceptical of all the bad press that adversarialism had received and was of the firm view that in certain circumstances adversarialism was nothing short of necessary. Success of non-adversarial approaches in the criminal justice system has often been limited to and has tended to focus on areas such as substance-abuse and mental health. Naturally then, I did not expect to walk out of a murder trial frustrated at the fact it was too adversarial, or what I would describe as unnecessarily adversarial. And yet, that is exactly what happened.

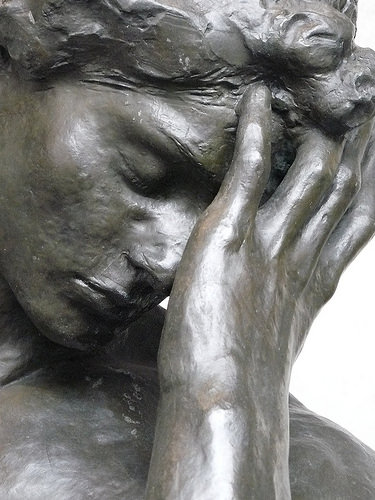

Perhaps setting the scene would prove helpful. Picture this: a quivering witness, a fully grown adult male, nervously sweating and anxiously fiddling with the pen in front of him, umming and ahing as he was cross-examined by the straight-faced defence counsel, looking back and forth between the judge, the lawyer, and the 12 members of the jury who all starred at this man. He had come forward to the police with his evidence out of his own choice, as he attempted to respond to, ‘You consider yourself a clever person, don’t you Mr X? So why can’t you answer my question with a simple yes or no?’ In the meantime, behind the patronising echoes of the defence counsel, tucked away at the back of the court, sat a man clutching a rosary as he attempted, and failed, at holding himself back from tears. A man who, at the end of the trial, may very well be spending the rest of his life in prison and yet his only contribution to this long and gruelling process was to sit at the back of the court room day after day, as mere observer in a trial that had the potential to affect the rest of his life.

Watching this scene unfold, I thought back to a passage from one of the introductory readings from the Australian Law Reform Commission 103 [1.119] for the Monash University Non-Adversarial Justice unit:

‘The term “adversarial” also connotes a competitive battle between foes or contestants and is often associated in popular culture with partisan and unfair litigation tactics. Battle and sporting imagery are commonly used in reference to our legal system. Lawyers’ anecdotes about the courtroom are “war stories”.’

Although, at the time, I thought of this passage as an exaggerated view of the adversarial system: mere hyperbole used in order to stimulate change, the scene I witnessed before me seemed to act out this description perfectly. As Enright puts forward in his article ‘Tactical Adversarialism and Protective adversarialism’, ‘many lawyers are culturally attached to, if not addicted to, the notion of adversarialism’ (Despite its attraction for lawyers, the prevalence of the adversarial system should be dependent on its functional adequacy and its ability to effectively and efficiently deliver the goals of the court.

2. THE ADVERSARIAL PARADIGM

The key aspect of Australia’s adversarial legal system is that it gives primacy to the parties. In essence, and as put forward by the Australian Law Reform Commission 103 [1.117], ‘the parties, not the judge, have the primary responsibility for defining the issues in dispute and for carrying the dispute forward’. The presiding judge takes no part in the investigation or the calling of evidence and their intervention during the trial is usually minimal. In Doggett v The Queen (2001), Gleeson CJ described such a system as reflecting ‘values that respect both the autonomy of the parties to the trial process and the impartiality of the judge and jury’. The adversarial system prides itself on certain strengths, which the Australian Law Reform Commission 32 [2.38] considers to include, ‘impartiality, independence, consistency, flexibility and the democratic character’ of its processes.

In Queen v Whithom (1983), Dawson J said that, ‘A trial does not involve the pursuit of truth by any means’. It has become rather evident that, in the adversarial system, justice means adherence to process. Truth is subservient to proof. Enright refers to adversarialism as a ‘prove it’ system, whereby the adversaries who access the court must prove their case to the required standard; it is then for the court to declare a ‘winner’. This imagery of competition and battle reoccurs throughout the literature analysing the system, highlighting that the framework itself is based on conflict rather than cooperation, a criticism of the system that will be discussed in relation to my personal observations.

3. PROBLEMS WITH THE ADVERSARIAL SYSTEM

Geoffrey Robertson QC in 1998 said in his book The Justice Game, ‘we can’t avoid the fact that the adversary system does make justice a game’. This focus on justice as something to be won or lost like a pawn on a chessboard, as opposed to the aspiration for justice to be attained, is certainly not a new image of the system. Enright tells us that, over time, the adversarial system has been described as one where the parties ‘fight the contest’ and become ‘ego-invested in appearing ‘right’ and ‘winning’’, where the focus is on ‘game-playing’, ‘ignoring the human element’, competing in a ‘battle’, which is a ‘fight to the death where the winner was the last man standing’ ().

Although I had hoped the above descriptions would be far from accurate when I witnessed a trial for myself, I can only say with grave disappointment that my experience of the adversarial system failed to prove those descriptions wrong. My critique, and therefore also my proposals for reform, focuses mainly on the defence barrister, who exploited his right to ask leading questions with total disregard for what effect this would have on the witnesses he was cross-examining. The barrister’s aggressive demeanour and patronising tone had different affects on different witnesses. Many looked as though they were uncomfortable, eager for their questioning to conclude so they could leave. Some became frustrated with the defence counsel’s approach, whilst others became genuinely distressed by the process. Even I, as an observer, felt uncomfortable and concerned for the witness. It is not that what the defence counsel was doing was wrong. Counsel was seeking to discredit witnesses and poke holes of doubt into the prosecution’s case; a reasonable approach to take. It is difficult to see, however, how these methods of using the witnesses merely as a means to an end can be justified. Moreover, as an observer, and as I suspect the jury felt, I couldn’t help but naturally feel against the defence. It is difficult to want to trust and believe someone who appears willing to go to any lengths to prove themselves right and ‘win’.

4. THE NEED FOR REFORM

The Hon Michael Kirby warns us not to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’. An adversarial system will inevitably give rise to adversarialism, and some adversarialism is indeed necessary. Although it is not recommended that adversarialism be removed in its entirety, (after all, it does come with its benefits), it is arguable that the system has become unnecessarily adversarial. Enright distinguishes between this ‘good’ and ‘bad’ adversarialism, distinguishing ‘protective’ adversarialism, which is essential for justice, and ‘tactical’ adversarialism, which is toxic to justice. He says that tactical adversarialism ‘occurs where the rules and practices allow a lawyer to attempt to win the case by means of tricks and stratagems that have no connection with the merits of the case’. It is this desire to win at all costs, which is sometimes referred to as ‘zealous advocacy’, that I was able to witness for myself in the defence lawyer (King et al, 2014, 266). It is this ‘tactical’ adversarialism, which is unnecessary and unjustifiably present in the justice system, that should be ‘thrown out’.

a. REFORMING LEGAL EDUCATION

Moving forward, one of the simplest and arguably most effective reforms would be in the field of legal education. Reforming legal education to focus less on what lawyers need to know and more on what lawyers need to do would help solve some of the problems with the adversarial system that were adumbrated earlier on. By reforming legal education, the legal profession is inadvertently affected and therefore, so is the justice system itself. Making positive changes to the way students are taught in law school would remove the unnecessary adversarialism in both legal practice and culture.

Currently in Australia, law schools are highly competitive environments that use case-based teachings, which focus on appellate judgments and use written examinations to assess students. Freiberg, in her journal ‘Non-adversarial approaches to criminal justice’, says that, ‘current teaching practices are, to a large extent, based on the adversarial paradigm’, but it is possible for this argument to work both ways. Although the adversarial framework of the Australian system has meant that legal education has followed this practice to give rise to law courses that are inherently adversarial, the emphasis law schools put on adversarialism has arguably fuelled or exacerbated this culture of competition and the image of the lawyer as a ‘zealous advocate’. In order to change the legal culture so that a defence lawyer doesn’t feel the need to push a witness to what might be described as the edge of having a breakdown, at the off chance that this would better help him ‘win’, it is necessary to address the problem at its root: law schools which plant seeds of adversarialism into each and every law student.

Countless reports and papers have been published recommending such reform. The Australian Law Reform Commission stated that legal education should focus on what lawyers need to be able to do, as opposed to what they need to know; the MacCrate Report by the American Bar Association in 1992 recommended traditional legal teachings be integrated with practical lawyering skills; the Carnegie Report said that there should be ethical and social skills teaching in order to engage the ‘moral imagination’ of students. How can these recommendations be brought to life in law schools?

The content of the curriculum of law schools requires change. The aims of law schools need to be re-evaluated and reflected through their teachings. The “Priestley 11”, as found in the Legal Profession (Admission) Rules 2008, which fails to address the need for practical skills, is somewhat out-dated. Freiberg provides a helpful list of items that the curriculum should also provide, including an understanding of the nature of conflict, skills in negotiation and mediation, subjects that were problem-based as well as doctrine- or theory-based, and an understanding that cases involve real people and therefore have psychological and emotional aspects to them.

Although making changes to the content of classes is a good place to start, it is not enough to remove the preoccupation of unnecessary adversarialism. In their journal article ‘The Law School Matrix: Reforming Legal Education in a Culture of Competition and Conformity Legal’, Sturm and Guinier say that education must move away from what they call a culture of ‘competition and conformity’, arguing that law school culture should be made an integral part of the conversation about law school reform. Their justification of which is that the legal culture will shape a lawyer’s ‘modes of thought, their language, their self image as professionals, their particular professional and organizational history’. It is evident, therefore, that the legal culture law students are nourished in, where they develop into lawyers, has a great effect on the legal profession as a whole. It is also important to recognise, however, that to change the legal culture, one that has been passed down through generations of lawyers and to which most legal professionals are attached, is not to be considered a light task and can only occur over considerable time. This is particularly so since law schools, as relatively conservative institutions, are rather resistant to fundamental change.

b. REFORMING THE ROLE OF THE JUDGE

Reforming legal education, although necessary, may have limited effects on the confrontational environment witnessed within a courtroom. A somewhat more drastic reform may look to alter the role of the judge to something more akin to the inquisitorial systems present in most of Europe, what many writers refer to as ‘active, not passive, judges’ (See, eg Freiberg, 2007, 217).

The inquisitorial system is dominated by the preliminary investigation stage where a file or dossier is prepared which is relied upon throughout the case and contains witness statements and all the evidence gathered. It is then the judge who presents the evidence and conducts the trial process whilst the lawyers play the more passive part. In some ways, the roles are the reverse of what is seen in an adversarial system. What this means is that although both systems have the seeking of truth as their aim, the adversarial system attempts to do this by pitting the two parties against each other in the hope that the competition will reveal the truth. This is one of the main reasons why the inquisitorial stem is far less confrontational and appears far less conflict-focused or competitive. Furthermore, because less emphasis is placed on oral evidence there is very little, if any, cross-examination of witnesses in the manner of an adversarial trial and it is the judge who conducts witness questioning. This means that the adverse affects on innocent witnesses, like those I had witnessed myself, are greatly reduced in the inquisitorial system. Moreover, since in the adversarial system it is the parties that choose which evidence to produce, there is no guarantee that they will present everything that is relevant if it has the potential to harm their case. This is, of course, avoided in the inquisitorial system where it is down to the judge to collect evidence and choose what should be presented.

It should be noted, however, that judicial impartiality is considered a major strength of the Australian adversarial system. Malleson described it as, ‘a key principle which is valued not just as a means of ensuring fair and truthful judgements but for its key role in maintaining public confidence in the decisions of the court’. The fact that the judge is independent of and separate from the prosecuting authority ensures that both parties are treated fairly and guarantees impartial treatment without bias. Former Chief Justice Gleeson referred to a judge’s demeanour as giving ‘to the parties an assurance that their case will be heard and determined on the merits, and not according to some personal predisposition on the part of the judge’. This effectively means the system is less prone to abuse and doesn’t promote bias.

5. CONCLUSION

Courts in common law jurisdictions such as Australia are a part of criminal justice system based on an adversarial system of law. The system relies on a two-sided structure of opposing sides that present their position on the case before an impartial judge. It is this framework, whereby adversaries are pitted against each other in order to reveal the truth to the judge, which creates an environment of tension and conflict within the courtroom. I had the opportunity to personally witness this confrontational setting in the context of a murder trial, and was critical of what I had observed. This essay therefore analysed the negative aspects of the criminal trial process that I was able to see, focusing mainly on the unnecessary adversarialism emanating from the defence lawyer.

One suggestion is the reform of legal education. This is arguably the best place to start in order to truly remove the negative aspects of the courtroom atmosphere such as conflict and confrontation. It would address the problem from its root by altering the curriculum to include non-adversarial classes but should also look to changing the culture of law school away from one of competition, where ‘winning’ is seen as the ultimate goal. A successful change in the culture of law schools would resonate through to the legal profession and the justice system.

A second proposal, which addresses the issues of adversarialism more directly but that is also a more substantive change to the current adversarial framework, would be to alter the role of the judge to be more like what exists in inquisitorial systems. In the adversarial system, the judge is often described as ‘impartial’. Lawton LJ said, ‘I regard myself as a referee. I can blow my judicial whistle when the ball goes out of play; but when the game restarts, I must neither take part in it nor tell the players how to play’ (Laker Airways Ltd v. Department of Trade [1977]). Such a system is often contrasted to the inquisitorial system where the judge has a key role to play in the investigation and the calling of witnesses. This shifts control of the case from the adversaries to the judge, diminishing the element of conflict between both sides and removing the power of the defence lawyer to create confrontation.

Although I believe there is a need to reform legal education, not only to keep up to date with the forever evolving justice system, but also to better the legal culture, I doubt it would be sufficient to have a substantial impact on the dynamics of the courtroom. For such a change, more direct reform is needed, for instance, the reform of the judicial role. It is, however, recognised that many legal professionals have a certain attachment to adversarialism and so the deep-rooted, entrenched legal culture and long-standing role of the judiciary will not be easy to uproot. Nonetheless, it seems to be the appropriate way forward in order to move away from the current system of conflict and confrontation.

Joana Bourouphael is a third year law student at the University of Warwick and is currently on one-year exchange at Monash University. Her enjoyment for advocacy has lead her to get involved in many mooting competitions, including the national Landmarks Chambers Mooting Competition 2016. She has also been involved in pro bono work with the Warwick Death Penalty Project Group, as well as with the Bar Pro Bono Unit. Additionally, she is set to trek Machu Picchu in aid of the Make-A-Wish in September 2017.

Twitter handle: @JBourouphael