Dr Becky Batagol, Monash University & Professor Rachael Field, Bond University

Email contacts: Becky.Batagol@monash.edu; rfield@bond.edu.au

This post comes from work we are doing together focusing on how to appropriately identify and respond to cases of family violence in mediation practice outside the area of family law.

This is our first time working together, after many years of knowing each other (we met at the National Mediation Conference in 2000). As two feminists, we are convinced that there are ways to make dispute resolution processes safer and more supportive for the women who must use them who are also victims of family violence. The project brings together Rachael’s expertise in crafting and evaluating a model for mediating family violence cases in family law through the Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution program and Becky’s expertise in family dispute resolution and follows from her work as a consultant to the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2015. (The views here are the views of the authors and not of their employers or organisations they have worked with previously).

Our work in this area is developing, and our thinking here is not final. We welcome your email or comment feedback. This post was developed from presentations at the 5th Annual Australian Dispute Resolution Research Network meeting in Hobart in December 2016 and at the AIJA Non-Adversarial Justice Conference, Sydney in April 2017.

Photo credit: Tom Simpson

Our aim in this project is to flesh out key elements of a safe and supported model of mediation in cases involving family violence that can be used across a range of contexts.

A great deal of attention has been paid to mediating cases of family violence in the field of family law. Outside the family law field, little attention has been paid to how to appropriately identify and respond to cases of family violence in mediation practice.

In our work together we are using what we have learned from family law dispute resolution to flesh out key elements of a safe and supported model of mediation in cases involving family violence that can be used across a range of contexts.

Beyond family law, there are a range of other contexts where dispute resolution professionals will have an ongoing role in dealing with the consequences of family violence eg

- disputes with providers of essential services, such as electricity, water, banking and telecommunications, as a result of economic abuse

- child protection conciliation conferences/ADR in state Children’s Courts

- the negotiation/mediation process that takes place in finalising the conditions of family violence orders in state magistrates’ courts, and

- restorative justice contexts as an adjunct to the criminal and family violence system

We believe that the imperatives relating to dispute resolution and family violence remain broadly similar regardless of the context. There is a legitimate concern about the use of informal dispute resolution processes in cases of family violence because of deep power imbalances between perpetrators and victims. On the other hand, with a focus on safety and with appropriate support and careful attention not to minimise the violence, there are clear potential benefits of mediation for victims of family violence which can include self-determination, certainty, reduced financial and other costs and timeliness.

We use the Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution model pilot to inform an analysis of the potentialities and possible pitfalls of the use of dispute resolution in the contexts outside family law

Context: Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution

In 2009, the Australian Federal Attorney-General’s Department commissioned a specialised model of family mediation for matters involving a history of domestic violence. The Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution model (CFDR) was piloted between 2010 and 2012 in five different locations around Australia, and evaluated by AIFS. CFDR was designed to support parties with a history of family violence to achieve safe and sustainable post-separation parenting outcomes. The model’s design sought to provide a multidisciplinary approach within a framework designed to specifically address some of the issues arising from a power imbalance resulting from a history of domestic violence. AIFS noted that the model is comprised of four case-managed phases which are implemented in ‘a multi-agency, multidisciplinary setting (which) provide a safe, non-adversarial and child-sensitive means for parents to sort out their post-separation parenting disputes’.

Eventually, funding was not provided for full roll-out of model due to political, resource and funding issues, although the fight for funding for CFDR continues.

The CFDR model was complex and multifaceted as the table below shows:

The special features of CFDR which work together to create the potential for safe and just outcomes – and which could be integrated into the diverse dispute resolution contexts we discuss further below – include:

- A coordinated response

The CFDR model demonstrated that it is important to bring a range of professionals together including government and community agencies to achieve a safe process, and it is critical that these diverse agencies and professionals share information and communicate effectively with each other.

2. A focus on specialist risk assessment

A critical element of the CFDR model was the integration of specialist risk assessment across the model’s practice which maintained the safety of the participants, and particularly the victims of violence and their children, as the highest priority. The safety focus of the risk assessment process went significantly beyond the usual FDR intake screening process which predominantly assesses that the parties’ have the capacity to participate effectively in the mediation process. These specialist risk assessments were conducted only by qualified and experienced DV and men’s workers with highly developed risk assessment skills, including an ability to identify ‘predominant aggressors’ of family violence.

3. The use of a legally assisted, facilitative model of mediation

In CFDR, a facilitative, problem-solving model of mediation was practised. This was because the goal of CFDR mediation was acknowledged as being to assist the parties resolve disputes about parenting safely, rather than to have a transformative effect. The design of the model acknowledged that it is not possible – in the 3-4 hours of a mediation session to have a transformative effect on perpetrators of violence. The best way to promote the safety of victims and their children was to support the making of relatively short-term parenting decisions. Transformative changes in a perpetrators violent behaviour may be possible but require the support and expertise of professional men’s behavioural change workers.

4. Special support measures needed to respond to domestic violence in mediation

The CFDR model also featured a number of additional special measures to protect the safety of victims and children. These measures were designed to support the hearing of the parties’ voices, and enable the parties to reach post-separation parenting agreements that upheld the best interests of the children. One such special measure was the acknowledgement of the concept of a ‘predominant aggressor’ in the model

5. Listening to the child’s voice

The involvement of children in CFDR mediation was not part of the general pilot process although the model as it was developed argued for inclusion of a professional children’s worker. If the child’s voice was included in the process it was only as a result of a decision by the CFDR team of case management professionals, and after careful analysis of the safety implications of this approach. Only appropriately trained and qualified ‘children’s practitioners’ could be asked to participate in CFDR to support the hearing of the child’s voice. These practitioners were required to have extensive clinical experience working with children and family violence.

The pilot was evaluated by the highly respected researchers at the Australian Institute of Family Studies under the leadership of Dr Rae Kaspiew. A number of the evaluation findings affirmed the efficacy of the design elements of the model in terms of facilitating the safe and effective practice of family mediation where there is a history of domestic violence. For example, it was found that adequate risk assessment for the parties’ safety and well-being is critical in domestic violence contexts; preparation for the parties’ participation in the process was key; and vulnerable parties have more chance of making their voice heard in mediation in the context of lawyer-assisted models, as long as those lawyers are trained adequately in dispute resolution theory and practice. In short the report said that CFDR was ‘at the cutting edge of family law practice’ because it involved the conscious application of mediation where there had been a history of family violence, in a clinically collaborative multidisciplinary and multi-agency setting.

Context: Royal Commission into Family Violence

The work of the Victorian Royal Commission into Family Violence, has shown that an understanding of the nature of family violence and an ability to identify and respond to cases of family violence is central to the work of anyone working in law and dispute resolution in a number of diverse fields.

The Victorian government set up the Royal Commission in 2014 to examine and evaluate strategies, frameworks, policies, programs and services and establish best practice for four areas – the prevention of family violence; early intervention; support for victims of family violence, particularly for women and children; and accountability for perpetrators of family violence. The Royal Commission was also asked to investigate means of ensuring systemic responses to family violence, investigate how government agencies and community organisations can better integrate and coordinate their efforts, and make recommendations on how best to evaluate and measure the success of strategies and programs put in place to stop family violence.

On 30 March 2016, the Victorian Parliament tabled the report of the Royal Commission into Family Violence. The report represents the culmination of 13 months of work by Australia’s first ever Royal Commission into family violence.

The Royal Commission’s report contains 227 recommendations. The Victorian government has committed to implementing all recommendations in the report, regardless of the cost. The Commission stated that its ‘recommendations are directed at improving the foundations of the current system, seizing opportunities to transform the way that we respond to family violence, and building the structures that will guide and oversee a long-term reform program that deals with all aspects of family violence’ (Summary and Recommendations, p.14).

We focus here on the recommendations which will affect the way in which a range of dispute resolution professionals will have an ongoing role in dealing with the consequences of family violence in our society.

Family violence-related debt disputes

Economic abuse is a form of family violence and is recognised as such in a few Australian jurisdictions.

The Royal Commission heard that most women who seek assistance for family violence issues leave their relationship with debt. Through the use of deception or coercion, perpetrators may avoid responsibility for a range of debts and leave their former partners with substantial liabilities (RCFV Report, Volume IV, chapter 21 p.102). This is a form of economic abuse, which is increasingly recognised as a form of family violence across the Australian jurisdictions. A recent RMIT analysis of ABS data showed that nearly 16 per cent of women surveyed had a history of economic abuse.

Women who have family violence-debt often have trouble negotiating the consequences of that debt with service providers. In their report Stepping Stones: Legal Barriers to Economic Equality After Family Violence, Women’s Legal Service Victoria noted that ‘service providers such as energy retailers, telecommunication services and banks have low awareness of the difficulties faced by women experiencing family violence and are unhelpful when interacting with these customers.’ Professor Roslyn Russell has recently shown how staff in bank branches and call centres report dealing with customers who are experiencing, trying to leave, or have left abusive relationships, yet there is limited training for banking staff on family violence.

A major proportion of Australia’s dispute resolution services are offered through industry ombudsman and complaint handling services such as the Victorian Energy and Water Ombudsman and the Commonwealth Financial Services Ombudsman and Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman. These services often use a combination of mediation, negotiation and conciliation to resolve disputes. It is clear these services are dealing with many disputes that arise with service providers as a result of family violence. Because such services are not part of the family violence system they may not have policies or training in place to identify or adequately address financial abuse and family violence.

The Royal Commission recommended that

- the Victorian Energy and Water Ombudsman and the Commonwealth Financial Services Ombudsman and Telecommunications Ombudsman publicise the availability of their dispute-resolution processes to help victims of family violence resolve disputes (Recommendation 110)

- comprehensive and ongoing training of customer service staff take place to help them identify customers experiencing family violence (Recommendation 109).

The Royal Commission’s recommendations are designed to develop employees’ capacity to understand, identify and respond to family violence within industry dispute resolution schemes so that victims of family violence can continue to access essential services such as household energy, water, telecommunications and financial services.

Negotiating family violence consent orders

Family Violence Intervention Orders (FVIOs) (also known as protection orders and apprehended violence orders in other jurisdictions), are orders made by the courts to protect a person from another family member who is perpetrating family violence.

There are often conditions attached to FVIOs which set out exactly what the perpetrator must do or not do in order to stop committing, and to prevent the future commission of, family violence. In Australia, FVIOs are made by state Magistrates’ courts.

The Royal Commission noted that ‘a high proportion’ of FVIOs are made by consent which means that the parties to the intervention order agree themselves to the FVIO and the conditions attached to the order which the Magistrate merely formalises (RCFV Report, Volume III, Chapter 16, p.134).

There is an incentive for perpetrators to settle orders by consent in the Victorian system because they can be made without the perpetrator admitting to any or all of the family violence allegations set out in the FVIO application.

However, for victims, there is a clear danger inherent in the negotiation process for consent orders, as described by the Commission:

‘the negotiation process involved in arriving at an order by consent may be opaque and variable depending on the situation, the parties and the presence of legal representatives. If there is a history of family violence between the parties, with everything that can entail – including an imbalance of power, fear, vulnerability, and the possibility of manipulation and coercion – it is extremely important that the negotiation process is properly managed. If the parties are not (or not adequately) legally represented, there is no guarantee that this will occur, and the result can be incomplete or inappropriate orders, whether on a primary application, a variation, extension or withdrawal, or a cross-application’ (RCFV Report, Volume III, Chapter 16, p.178).

Mediation is not formally part of the process for negotiating FVIOs in Victoria, although it is in the ACT, the only such jurisdiction in Australia to use mediation formally.

The danger of any negotiation process used to determine the terms of FVIOs is that it is the very acts of family violence that are being discussed and negotiated, and that a poor process may result in a poor order with conditions that fail to protect the victim and her children.

Because so little is known about the process for negotiating consent orders for FVIOs in Victoria, the Royal Commission adopted a cautious approach and recommended that a committee be established within the next three years to investigate how consent-based family violence intervention orders are currently negotiated and to develop a safe, supported negotiation process for victims (Recommendation 77). On this issue, the parallels to family dispute resolution are clear.

Restorative Justice and Family Violence

Restorative justice is a process which was developed from the criminal justice system which enables all parties who have a stake in an offence to come together to discuss the aftermath of the offence and implications for the future. While restorative processes have a criminal provenance, which makes them distinct from DR processes such as mediation and conciliation, the processes share in common a commitment to party empowerment and a sense that creative solutions can be found through ‘talking it out’ which would not be possible in the formal legal system.

The Royal Commission noted that while the justice system plays a fundamental role in protecting victims’ safety and promoting perpetrator accountability, that many women find the reality of the court process to be deeply dissatisfying and even re-traumatising: ‘A strong theme that emerged from consultations held by the Commission was the need for victims to understand the options available to them, and the process involved, and to be empowered to make their own decisions about what steps and outcomes are appropriate’ (RCFV Report, Volume IV, Chapter 22, p.136).

Restorative justice programs have the potential to provide family violence victims with the chance to be heard, to explain to the perpetrator what the impact of the violence has been and to be empowered to discuss future needs, including any reparations. Such a process potentially places great power in the hands of the family violence victim.

However, the same concerns can be raised about the use of restorative justice in family violence cases as there are about the use of family mediation in cases of family violence. The concerns about use of restorative justice in this context include unequal power relationships between victims and perpetrators, concerns about safety, and concerns about the appeal to apology and forgiveness which are part of the cycle of abuse in family violence.

The Commission concluded that restorative justice processes have the potential to assist victims of family violence to recover from the impact of the abuse and to mitigate the limitations of the justice system (RCFV Report, Volume IV, Chapter 22, p.143). The Commission recommended that within two years a pilot program be developed for the delivery of restorative justice options for victims of family violence which would have victims at its centre, incorporate strong safeguards, be based on international best practice, and be delivered by appropriately skilled and qualified facilitators (Recommendation 122).

Common elements of diverse family violence dispute resolution contexts?

So, what are the common elements of diverse family violence dispute resolution contexts? It is worth considering commonalities between the processes so that we can understand the nature of the dispute resolution content and process. This will better enable us to understand what elements are needed for dispute resolution processes across these diverse contexts.

We see the common elements of the diverse family violence dispute resolution processes as follows:

- Victim is part of dispute resolution process.

Across each of the three contexts, the victim of family violence will usually be part of the dispute resolution process. However, the victim may not be there in person (such as through resolution of disputes through ombudsman services, the dispute may be dealt with on the papers).

2. Perpetrator may or may not be part of dispute resolution process.

While the victims will be part of the process, the perpetrator may not always be there. For example, in debt disputes, the victim may be left with a debt and be unable to pay. The perpetrator may not be available or should not always be asked to explain or confirm his actions. However, in restorative justice conferences, the perpetrator may be there. In this case, safety issues must be paramount

3. Family violence may be hard to identify.

We know reporting levels of family violence are low. Matters in dispute may not initially present as a family violence matters. However, family violence may be central to matter, but extent of family violence may be hard to identify.

4. Family violence will affect how the victim will behave.

Victims of family violence are often vulnerable. The violence they have experienced will affect how they will behave in a legal or dispute resolution process.

5. Family violence is central to the nature of the dispute, the process and the outcome.

A “Safe and supported” mediation model

What then are the key elements of a safe and supported mediation process that could be used as the basis of new dispute resolution processes for cases involving family violence across a broad range of contexts? To develop these elements we draw from what we have learned in developing Coordinated Family Dispute Resolution in Australia from 2010.

We propose a “safe and supported” mediation model.

We have chosen to focus on a single dispute resolution process, mediation. Mediation is widely used. It offers flexibility and compromise between party empowerment and professional control of the process. Professional control of a process is central in cases of family violence where the risk of harm is great.

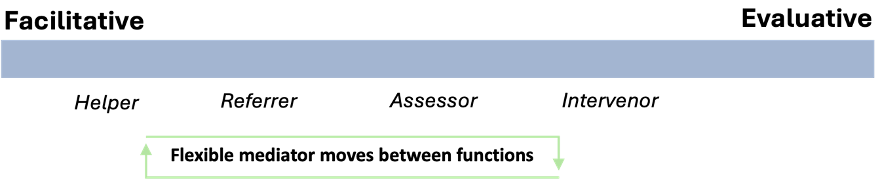

We believe that facilitative mediation is the best type of mediation in cases of family violence. A process like facilitative mediation carries with it the possibility of compromise between party autonomy and mediator control of the process necessary to provide a safe and supported negotiation process in the shadow of family violence. It also focuses on problem solving of the issue at hand, without attempting to remedy the relationship (as in transformative processes) which is arguably inappropriate in cases in family violence.

We believe that victim’s safety must always be the key priority in any dispute resolution process involving family violence. The victim’s safety must not be compromised because of her involvement in a legal process and the outcome of the negotiation must always be measured against the goal of ensuring safety for victims of family violence.

We focus on support because this is a key means of providing victims of family violence with the ability to participate in informal dispute resolution processes.

Elements of a “safe and supported” mediation process for matters involving family violence

Drawing from the CFDR model, the following are elements which we propose could be part of mediation processes involving family violence. These elements could apply across the full range of contexts mentioned above. It may be that some elements cannot be used in specific contexts. Nevertheless, dispute resolution processes for cases involving family violence should seek to implement as many of these elements as possible.

- That issues of safety and risk are placed at the heart of decision-making.

- The philosophy behind the dispute resolution process is that perpetrator accountability is a central objective of any mediation process that seeks to work effectively in contexts where there is a history of family violence.

- It is central that the family violence itself is not negotiated.

- A range of professionals must work together to achieve a safe process. It is critical that these diverse agencies and professionals share information and communicate effectively with each other.

- Specialist risk assessments must be conducted only by qualified and experienced family violence and men’s workers.

- A legally assisted, facilitative model of mediation should be employed.

- There must be acknowledgement of the concept of a ‘predominant aggressor’ in the dispute resolution process. This is especially important where there are cross-allegations of violence against each party, which increases the risk that tactical allegations of family violence could be used to cover up for legitimate allegations.

- Where perpetrators are involved in the dispute resolution process, the minimum expectation for participation in the model (and to receive its benefits such as free legal advice, counselling and other supports) is that perpetrators should have to acknowledge that family violence was an issue for their family, and that a family member believes that family violence is relevant to working out the future arrangements for the children.

- There must be training for dispute resolution practitioners in the nature of family violence and family violence identification

We acknowledge this this post presents the first stage in our thinking about the use of dispute resolution processes for the management or resolution of disputes beyond family law and in contexts of family violence.

More specific work needs to be done to create context and organisation-specific models of mediation which acknowledge the existence of family violence in disputes and to adequately address the needs of the parties in light of family violence.

We think that the effort that has been put into working with clients around family violence in family dispute resolution holds important lessons for those in other dispute resolution contexts.

The elements of a “safe and supported” mediation model for matters involving family violence that we propose are an important starting point in a conversation about the safety and needs of victims of family violence in our society.

Please let us know your thoughts as we continue to develop our model.

Email contacts: Becky.Batagol@monash.edu; rfield@bond.edu.au