Dan Berstein

Whatever the reason for it and whoever it comes from, rejection hurts.

In 2022 I wrote a book called Mental Health and Conflicts: A Handbook for Empowerment with hopes to teach people skills for managing challenging behaviors without writing off people with mental illnesses. At the time, this book represented a culmination of my life’s work and it meant a lot for to me that it found a home at the American Bar Association (ABA).

Three years later, my ABA affiliation was unfortunately terminated following a difficult saga, for me and many others, as I was wrestling with interpersonal struggles and bipolar symptoms. The news of my termination was very difficult. I have been hospitalized five times due to my bipolar disorder–always during times when I became overwhelmed by similar interpersonal challenges. During each episode, I would break down, my mind would get stuck on a problem, and I would decompensate into mania or even psychosis. My condition has a high risk for instability and suicide, with research showing that each subsequent episode means a decreased odds of returning to normal functioning.1

Being terminated from the ABA overwhelmed me. It was a sudden emotional crisis that put me at risk. I required emergency medication, emergency therapy sessions, and emergency support from friends and family. We summoned all of the lessons from decades of managing my condition in order to make it through.

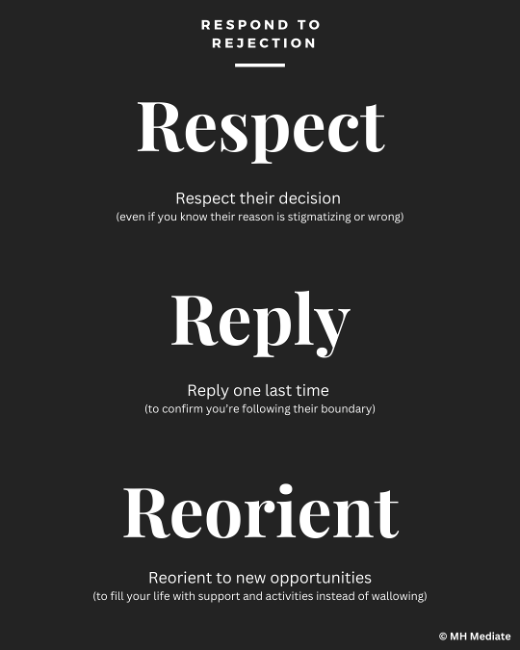

Even though it was an immensely challenging period in my life, this time something was different. In 2023, and as part of my professional work as a conflict resolver, I had developed a system for responding to avoidance, rejection, and social exclusion. I presented a three-step model to get through these especially challenging situations, which I call the 3 R’s, at the Association for Conflict Resolution conference and the Academy of American Law Schools ADR Works-In-Progress conferences.

Without the skills of the 3 R’s, I do not know how I would have coped with being terminated. That system consists of:

- Respect.

- Reply.

- Reorient.

The 3 R’s approach readily lends itself to any situation and can be easily used by anyone when they face rejection from friends, family, colleagues. Here’s how it works:

1. Respect the person’s decision even if you find it stigmatizing or you disagree with it.

While it is tempting to try to convince them of your worth, dispel lies or inaccuracies, and seek ways to still have the relationship, it can also be dangerous.

Sadly, I’ve learned in my life that, given I’m open with my bipolar disorder, it is easy for people to stigmatize my persistence to fight being rejected. Studies have shown that it is common that people with bipolar disorders are sensationalized in the media (such as TV shows or movies, and other portrayals).2 There is also research that shows people are more likely to worry someone that has a mental health problem is some kind of stalker.3 Amidst that kind of climate, it can be risky to continue contacting someone who may be seeing any follow-up through a stigmatizing lens. Arguing with their portrayal may only feed into the narrative.

Stigma aside, in any conflict it is helpful to separate the person’s decision to cut contact with you from the explanation you are given or the style with which it is delivered. It may feel offensive, demeaning, disrespectful to be ghosted or to hear a story that does not ring true or clearly is contrived. But no matter how poorly implemented or inaccurate the rejection may seem to be, it still provides notice of a decision: however painful the circumstances, this person wants to diminish or end their relationship to you.

Years of dispute resolution have taught me to prioritize self-determination,4 and made it easier for me to come to a place of accepting that a person made a rejection decision.

While it does not feel good to be rejected, it has been a relief to readily accept it instead of debating. If there are other problems related to what is happening, such as bullying or discrimination, it still can be best not to fight and instead look for other kinds of support.5

2. Reply one last time to confirm the boundary.

You may not always get a formal letter or confirmation (such as a letter of termination–like I received) when it comes to rejection and social exclusion with friends, family, or others.

We live in a world filled with “ghosting” patterns–where people just pull away without contact–and things are left rather ambiguous and unclear.6 Sometimes it can be extremely ambiguous, such as in one of the latest dating trends where people engage in “breadcrumbing” to keep romantic partners on the hook or on hold.7

This is why, whenever anyone seems to be avoiding contact with me, I send one final reply to let them know that I am acknowledging what I perceive to be their boundary to be and that I plan to follow it. Depending on your personal boundaries, you might also let them know you are available in the future if they change their mind on reconnecting. In the course of my mental illness discrimination advocacy work, I typically take that approach, with hopes that one day the people or organizations who are avoiding me will evolve and want to engage. In that case, I want them to know the door is still open for that.

Sending this reply is important because it is possible–given any ambiguity–that there was a misperception. Sometimes people will immediately let you know that they didn’t mean to make you feel rejected and they might undo the boundary. On the other hand, if they are intent on the rejection, your reply documents that you are honoring their boundary and that record can be helpful, particularly to guard against the stigmas mentioned earlier.

3. Reorient to next steps rather than stay stuck in pain.

This is my favorite “R” because this approach has truly changed my life. Before the 3 R’s, I would stay fixated obsessing on hating myself, endorsing self-stigmas, wallowing, and reliving the loss over and over whilst descending into a dark place in my mind.

But there is another way. If we commit to focusing on reorienting ourselves to discover new opportunities, we can enrich our lives. Since I started using the 3 R’s model in my life, I have connected with new friends and colleagues, developed new projects and partnerships, and become active in new communities–all because I decided to immediately accept the person’s decision to cut contact with me and start looking for new people and places to be involved instead. Since 2023, when I first created this system, my life has grown at a meteoric rate with many new opportunities which I have found and nurtured every time I reorient.

My initial connection to Australia came by my efforts to reach out to someone in early 2024 and during a time when I received a different rejection letter related to my anti-discrimination advocacy work. This new relationship was a welcoming one where we collaborated on programs, and eventually led to a conference invitation from someone else and then to my writing on this Blog. None of this would have happened if I had not decided to reorient and move forward. And that example is just a fraction of the rich relationships I have developed when I took chances on reorienting toward new things instead of fighting to cling onto what I had already lost.

I am sad that my bipolar disorder and interpersonal struggles led to difficult circumstances with the ABA and led to my termination. At the same time, I am grateful that the 3 R’s helped me get through it and land on my feet. This method has helped me in a time of need where I have felt unwelcomed in any community or with any person. Remembering to do it when I am feeling hurt has allowed me to make healthier, more empowering decisions.

Even when I was so dysregulated by my serious mental illness and wrestling with an influx of distressed energy, I was still able to tap into those 3 R’s to ensure I made the best possible decisions to:

- Respect peoples’ choices instead of fighting to prove my worth,

- Reply to work things out instead of begging to return, and,

- Reorient to fill my life with opportunities that were a better fit for me and my sometimes-challenging mental health problems.

I will still love the American Bar Association, albeit from afar and via nostalgic memories, I still have a page posted summarizing much of my anti-discrimination work there and other projects from my four years as Co-Chair of the ABA’s Dispute Resolution Section Diversity Committee. During this time, I made many friends and did a lot of important work. Though I will certainly miss being connected with so many great opportunities and new ideas, I will keep reorienting amidst the loss. Meanwhile, I will always recommend that anyone who does have access avail themselves of the myriad of resources disseminated by the ABA and often developed from their community of over 200,000 members.

The 3 R’s have helped me prevent complete breakdowns and manage challenging times in my life. These skills have helped me find and new opportunities during times I might have otherwise fallen apart. Anyone can use this simple yet powerful system when they face rejection in their lives.

Author Biography

Dan Berstein is a mediator living with bipolar disorder who uses conflict resolution best practices to promote empowering mental health communication and prevent mental illness discrimination. His company, MH Mediate, has helped thousands of professionals and organizations be empowering, accessible, and non-discriminatory toward people with disclosed or suspected mental health problems. Dan holds degrees from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the Wharton School. He is the author of the 2022 book, Mental Health and Conflicts: A Handbook for Empowerment.

- Gergel, T., Adiukwu, F., & McInnis, M. (2024). Suicide and bipolar disorder: opportunities to change the agenda. The Lancet Psychiatry; Peters, A. T., West, A. E., Eisner, L., Baek, J., & Deckersbach, T. (2016). The burden of repeated mood episodes in bipolar I disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 204(2), 87-94. ↩︎

- Klin, A., & Lemish, D. (2008). Mental disorders stigma in the media: Review of studies on production, content, and influences. Journal of health communication, 13(5), 434-449. ↩︎

- Wheatley, R., & Underwood, A. (2023). Stalking and the impact of labelling “There’sa difference between my offence and a stalker”. Journal of criminal psychology, 13(2), 91-104. ↩︎

- Baruch Bush, R. A., & Berstein, D. (2023). Orienting Toward Party Choice: A Simple Self-Determination Tool for Mediators. J. Disp. Resol., 1. ↩︎

- Tuckey, M. R., Li, Y., Neall, A. M., Chen, P. Y., Dollard, M. F., McLinton, S. S., … & Mattiske, J. (2022). Workplace bullying as an organizational problem: Spotlight on people management practices. Journal of occupational health psychology, 27(6), 544. ↩︎

- Freedman, G., Powell, D. N., Le, B., & Williams, K. D. (2019). Ghosting and destiny: Implicit theories of relationships predict beliefs about ghosting. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(3), 905-924. ↩︎

- Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2020). Psychological correlates of ghosting and breadcrumbing experiences: A preliminary study among adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(3), 1116. ↩︎