By Dr Samantha Hardy and Dr Judith Rafferty

This article has been republished (with minor amendments) with permission. The original publication can be found at The Conflict Management Academy.

Apologies can be transformative. A genuine “I’m sorry” has the potential to mend trust, restore dignity, and signal a willingness to move forward. Yet in practice, many mediators have sat through sessions where one party waits, sometimes desperately, for an apology that never arrives. The other party’s refusal to apologise can stall dialogue, harden positions, and frustrate attempts at resolution.

This post explores the dynamics at play when apologies are withheld. We will look at why people seek apologies, why others resist offering them, what options exist when an apology never comes, and how mediators can manage this fraught terrain.

1. Why someone might want to receive an apology

An apology might meet different needs for the receiver:

- It might provide recognition of the impact of the other’s actions on the receiver. It might validate the receiver’s pain and suffering.

- It might confirm that what happened was “wrong”, providing a sense of justice to the receiver.

- It might restore a sense of power or control to the receiver. An apology can restore autonomy by giving them the power to accept, reject, or withhold forgiveness.

- It might reaffirm shared values and expectations around behaviour. An apology communicates renewed consensus around those values, reinforcing the idea that both parties agree on what is acceptable behaviour in the future.

- High-quality apologies can also reduce anger, increase empathy, and foster willingness to reconcile. This is particularly important in ongoing relationships such as workplaces, families, or communities.

2. Why someone might not want to apologise

If apologies are so powerful, why would someone refuse to offer one? The psychology is complex. Research has identified several barriers and motivations:

They don’t feel like they’ve done anything wrong

Many equate an apology with an admission of guilt. For those convinced they acted correctly, an apology can quickly feel exaggerated or unjustified.

Fear of consequences

Some worry that an apology will be interpreted as an admission of guilt, exposing them to criticism, sanctions, or even legal liability.

Protecting self-esteem

Apologising can feel like a loss of face, signalling that your standing is diminished in front of the other person. For those with fragile self-esteem, the psychological discomfort may be too great. Karina Schumann’s work highlights “perceived threat to self-image” as one of the strongest barriers to apologising.

Concerns about power and control

Okimoto, Wenzel, and Hedrick (2013) found that refusing to apologise can actually increase a person’s self-esteem by enhancing feelings of power and value integrity. By withholding an apology, people may feel they retain dominance and control.

Low concern for the relationship

Some simply do not value the relationship enough to invest in the discomfort of apologising. Low empathy, extreme self-interest, or avoidance of closeness can all reduce the likelihood of apology.

Perceived ineffectiveness of apology

Even when someone recognises that they caused harm, they may doubt whether apologising will help. They might expect rejection or believe the other person will not forgive them anyway.

Defensive fragility mistaken for strength

As psychologist Guy Winch notes, people who cannot apologise often appear tough, but their refusal usually reflects deep vulnerability and fragile self-worth.

They have already apologised

Sometimes people refuse to apologise in a mediation because they have already apologised (one or more times) and it hasn’t made any difference.

They don’t want it to be a trigger

Occasionally an apology can act as a trigger, reminding people of the circumstances and hurt of the past. Some people wish to avoid that and just “move on”, leaving the past behind.

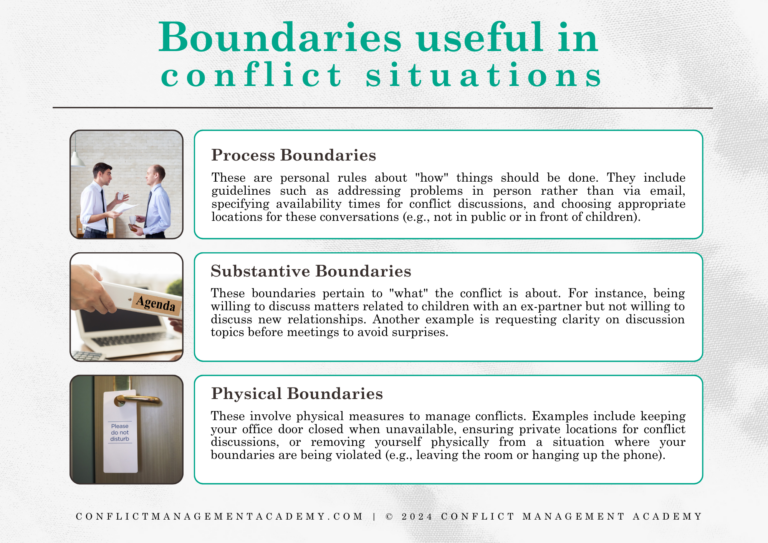

3. What to do when someone refuses to apologise

In many mediations, a party may openly state that they want an apology. When it does not come, the process risks collapsing into impasse.

For mediators, it is important to see refusal not simply as obstinacy but as a defensive strategy rooted in self-protection, power, or relational disengagement.

Here are some strategies for mediators to help parties navigate this reality.

Manage expectations early

At the start of the mediation, clarify that apologies may or may not occur. This helps prevent disappointment later if one party was anticipating an apology as the main outcome. Mediators can also normalise the difficulty of apologising. Mediators can gently explain that apologising is psychologically hard for many people. This can reduce personalisation of the refusal.

Attend to power dynamics

Because apologies carry symbolic weight around power and control , mediators should be alert to how apology refusal may entrench dominance. They may need to balance this by giving the other party more voice or decision-making space.

Explore the interests underlying both the request for an apology and the refusal to give one

Ask the person who wants the apology to give an example of the kind of apology they would ideally like to receive, and explain the impact it would have on them. Often, the need is for recognition, respect, or validation rather than the exact words “I’m sorry.” Mediators can help the party articulate what they hope to gain and explore other ways of meeting those needs.

Non-judgementally, ask the person who refuses to apologise to describe their reasoning. Listen for some of the reasons outlined above, and direct your interventions to exploring and responding to those needs.

These questions are probably best asked in private sessions so that parties have a safe space to be vulnerable. From their answers, you may be able to identify what needs the apology (and not apologising) would meet and then work to brainstorm different ways to meet those needs.

Refocus the discussion to intent and impact

Supporting parties in mediation to clarify intent and impact can help address misunderstandings which may make the desire for apologies and the apology itself obsolete. Of course, clarifying intent and impact can also help people who weren’t aware of any wrongdoing gain awareness that their actions, even if meant/ intended otherwise, caused harm for the other and may thus increase the other’s desire and the actor’s awareness for a need for an apology. Apologising for something that had a different impact to what was intended could also be “easier” in the sense that it may be less threatening to self-image – after all, the actor had not had any intentions, but misunderstandings (external factors) may have led to the misperception of harm.

Support vulnerability and self-esteem

Support the person who does not want to apologise to explore ways of being vulnerable while still maintaining safety and self-esteem.

Mediators can help parties to identify substitute behaviours.

Sometimes, non-apologisers express contrition indirectly: by being extra kind, cooperative, or attentive after the fact. Mediators can help parties notice these gestures as alternative forms of repair.

Sometimes parties resist the word “apology” but are willing to express regret or acknowledge impact. Mediators can explore softer or alternative language that validates the other person without requiring full admission of fault.

Explore ways of meeting the requesting party’s needs by framing things in different ways that may or may not look exactly like an apology.

Importantly, mediators need not overemphasise hearing the words “I’m sorry.” Expressions of genuine remorse, awareness of impact, or acknowledgement of harm can often meet the deeper needs more effectively than the word itself.

Elicit reflection on meaning of apology

In private session, mediators can ask the person refusing to apologise: “What would it mean for the other party to hear you apologise?” This question does not pressure them to apologise, but it can prompt reflection on the potential value of an apology for the other person. At times, this reflection has opened space for an apology to emerge.

Use reframing techniques

If a party expresses their refusal bluntly (“I’m not going to apologise”), mediators can reframe this as an attempt to hold onto integrity or avoid insincerity. This can de-escalate defensiveness and allow conversation to continue.

Reality test

Ask the person who does not want to apologise what they potentially stand to lose and gain from apologising.

Ask the person who wants the apology what their choices are if they don’t receive it.

Invite reflection on choice

Mediators may also be able to encourage acceptance without agreement. Radical acceptance helps individuals acknowledge painful realities without condoning them. For example, someone may not receive an apology but can still choose to accept the situation and move forward with their values intact.

When a party faces the absence of apology, mediators can help them consider whether to persist in the relationship, renegotiate boundaries, or disengage altogether. As one writer put it: “Life becomes easier when you learn to accept an apology you never got”.

Invite mutual apologies

I also feel we should talk about situations where both parties are requesting an apology from each other and how that can create additional impasse or help the situation, since it balances the “power” a little.

Facilitate mutual checking for understanding

Invite each party to check that they have understood the other, including naming what was most difficult or hurtful in the conflict. Then ask the original speaker to confirm – “Did she/he get that right?” This creates a moment of empathy and can soften defensiveness. It also lays the groundwork for acknowledgement by ensuring that each person feels genuinely heard.

Shift the focus to future arrangements

If apology is not forthcoming, help parties reorient toward practical agreements. What changes in behaviour, communication, or boundaries could rebuild trust without requiring an explicit apology?

Support emotional closure without apology

Through reflective listening, summarising impacts, and validating emotions, mediators can help parties feel heard even in the absence of an apology. This may provide enough recognition to allow agreements to move forward. Research suggests there can be significant psychological benefits in choosing to let go of anger and resentment without an apology – including in situations where extreme harm has been suffered – showing how this approach can strengthen resilience. Recognising this possibility may open space for parties to consider new pathways to closure.

Conclusion

Refusal to apologise is one of the thorniest issues mediators can encounter. For the person harmed, it can feel like justice denied. For the person refusing, it can feel like self-preservation. And for the mediator, it can feel like an immovable barrier.

Yet by understanding the psychological underpinnings, mediators can reframe the impasse. People seek apologies for validation, dignity, and reaffirmation of values. People withhold apologies to protect self-image, preserve power, or because they doubt its effectiveness. When apologies do not come, parties can still find closure through acceptance, alternative forms of recognition, and practical agreements.

For mediators, the task is not to extract apologies but to help parties understand and meet underlying needs. With skill, patience, and creativity, even the absence of “I’m sorry” can become the starting point for resolution.