In this post we think about the psychological and neuro-science impacts on our efforts to prevent, manage and resolve disputes in lockdown. This is another area where we need to enact our dispute resolution agency to be effective communicators in our homes and workplaces during COVID-19.

Mediation and the Brain

Psychology is about how the human brain works. The workings of the human brain are an increasingly important knowledge base for mediators and in lockdown we can learn from the art of mediation in this regard. In lockdown discussions we need to be aware of, and take into account, our relative emotional and psychological states.

We can no longer assume that individuals make utilitarian decisions on a rational basis, in the promotion of their own self-interests and in terms of objective cost-benefit analyses of their options. Such assumptions have been challenged, amongst other things, by the disciplines of behavioural economics, cognitive psychology, game theory, neuro-science and decision theory.

In mediation and in lockdown communications we need to expect some level of ‘irrationality’ in terms of our problem-solving and decision-making as humans. Studies in cognitive psychology, for example, have demonstrated through observation, experiment and surveys that many people are guided by cognitive and social biases, heuristics and other unconscious factors when they make decisions and not by conscious rational considerations.

Various cognitive and social biases have implications for mediation and other DR processes:

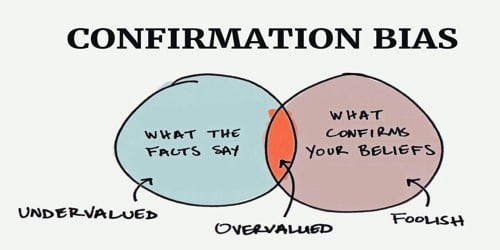

First, the confirmation bias involves parties being selective in their choice of facts and evidence, accepting and emphasizing what supports their preferred outcomes to a situation and ignoring, marginalizing or rejecting the information which undermines it. This bias is essentially a form of one-eyed self-deception which is widespread in dispute situations.

Second, the anchoring bias involves parties being unconsciously influenced by a number or dollar figure provided from negotiating opponents, or even from an extraneous source, and adjusting their expectations and negotiation range accordingly.

Third, the optimistic over-confidence bias involves persons betting themselves ‘against the odds’ and expecting to do better than the average, for example franchisees in a particular industry or claimants in vehicle accident compensation cases.

The many unconscious biases in human decision-making cause parties in mediation to diagnose conflicts inaccurately and to intervene inappropriately, not only frustrating attempts at settlement but prospectively causing disputes to escalate in extent and intensity. The biases can also operate cumulatively – for example an employee’s confirmation bias about the circumstances of their removal from office is likely to exacerbate their unrealistic over-confidence about achieving a positive outcome to a dismissal claim, such as reinstatement, or a higher than normal damages settlement.

While artificial intelligence (AI) claims to avoid or annul many of these features of the human condition, decision-making biases can also be inadvertently embedded in software and algorithms and thereby impose residual preferences on decisions.

Mediation and Neuro-Science

Neuro-science adds to the knowledge base of psychology through observation and analysis of actual brain activities in human subjects. Through imaging of physiological, electrical and chemical impulses in the brain, scientists can observe the impacts on the brain’s neural pathways, and different parts of the brain, when a patient or subject is exposed to different sounds, sights, words or other stimuli.

A compelling illustration of these insights is provided in relation to the phenomenon of loss aversion, one of the cognitive biases previously identified by psychologists. When subjects undergoing brain-scanning are exposed to the single words ‘loss’ or ‘gain’ there are profound differences in the observed neural impacts – in broad terms the former term has an effect several orders of magnitude greater than the latter, in respect of both intensity and duration. In this instance the brain science reinforces orthodoxy long prevalent in mediation theory: parties who perceive they are facing a loss are likely to be risk-accepting and seek an outcome away from the mediation, but if they perceive a gain at the mediation table they are likely to be risk averse and favour settlement. Brain scanning provides corroboration and a deeper explanation for the phenomenon, founded on human survival instincts, which responds to threats more intensely than to rewards. While survival instincts arose originally in relation to physical threats, they are now also a product of perceived unfairness, undignified treatment, negative emotional experiences or unfulfilled expectations in the mediation room.

A compelling illustration of these insights is provided in relation to the phenomenon of loss aversion, one of the cognitive biases previously identified by psychologists. When subjects undergoing brain-scanning are exposed to the single words ‘loss’ or ‘gain’ there are profound differences in the observed neural impacts – in broad terms the former term has an effect several orders of magnitude greater than the latter, in respect of both intensity and duration. In this instance the brain science reinforces orthodoxy long prevalent in mediation theory: parties who perceive they are facing a loss are likely to be risk-accepting and seek an outcome away from the mediation, but if they perceive a gain at the mediation table they are likely to be risk averse and favour settlement. Brain scanning provides corroboration and a deeper explanation for the phenomenon, founded on human survival instincts, which responds to threats more intensely than to rewards. While survival instincts arose originally in relation to physical threats, they are now also a product of perceived unfairness, undignified treatment, negative emotional experiences or unfulfilled expectations in the mediation room.

Through brain-scanning and other investigative procedures, neuro-scientists have provided far-reaching evidence and understanding of how electrical messaging and chemical releases operate under conditions of stress, emotion and ambivalence, all of it potentially relevant to mediation. For example, mirror neurons in one party’s brain can be activated by agitations in those of another person, leading to emotional contagion among disputants in high-level conflicts. The chemicals dopamine, oxytocin, adrenalin and cortisol are released in response to specific pleasurable or stressful circumstances, including those encountered in the mediation room, and they affect respective parties’ behaviours, judgments and decisions. The plasticity of the brain, however, entails that its operation is not always predictable and it can change its habits and patterns over time.

Another dimension of brain science derives from the organ’s bicameral structure. In 2017 Australian judges were addressed on the divided brain by an English psychiatrist, Ian McGilchrist, his work drawing on science, philosophy, literature and culture. He accentuated the significance of brain bicameralism in many aspects of human affairs and societal development – and by implication in dispute resolution activities. A more dated ‘left brain-right brain’ notion had been prevalent decades earlier, associating the left with attributes such as logic, language and analysis and the right with factors such as emotion, affect and art. This construct had in some respects been overtaken by work on the triune brain, and its implications, referred to above.

Another dimension of brain science derives from the organ’s bicameral structure. In 2017 Australian judges were addressed on the divided brain by an English psychiatrist, Ian McGilchrist, his work drawing on science, philosophy, literature and culture. He accentuated the significance of brain bicameralism in many aspects of human affairs and societal development – and by implication in dispute resolution activities. A more dated ‘left brain-right brain’ notion had been prevalent decades earlier, associating the left with attributes such as logic, language and analysis and the right with factors such as emotion, affect and art. This construct had in some respects been overtaken by work on the triune brain, and its implications, referred to above.

McGilchrist’s work essentially re-affirms in more erudite terms the significance of the two hemispheres, while emphasising that both sides are involved in all brain functions, from thinking to feeling and from mathematics to imagination, and continuously communicating with each other. However, despite the hemispheres being interdependent in all brain activities, each has significantly different ways of operating.

At a simplified level the brain spheres can be differentiated as follows: the left hemisphere is analytical and linear, it fragments experiences and operates with patches of information as opposed to whole entities and it uses categories and concepts in predictable patterns – ‘claimant’, ‘respondent’, ‘damages’ and the like. It has a narrow focus of attention and tends to decontextualize, divide and simplify, providing a ‘re-presentation’ of the world. Above all the left hemisphere is where our competitive instincts reside, it is utilitarian in focus and, importantly for mediation, it is convinced of its own rectitude and has difficulty changing its mind.

The right hemisphere is where new experiences are initially processed. It provides a big-picture assimilated view of the world, deeper and wider than the localised short-term view of the left. It has integrative powers, providing a more complex and connected picture of reality than the left, and it is more intuitive, imaginative and empathetic. Here there is a richness of thought, stimulated by gesture and symbol, poetry and myth, music and metaphor. Moreover, the right hemisphere operates largely at an unconscious level with few of our experiences and effective decisions, that McGilchrist suggests, operate within our actual consciousness.

The hemispheric modes of experience can be significantly opposed in their approaches and are sometimes in states of conflict. Human decision-making, whether in personal, business or mediation contexts, is initially dictated by the right hemisphere, albeit at an unconscious level. The complexity of thought in the right segment is then translated into the (sometimes simplistic) language and categories of the left. The ongoing development of the left hemisphere over the ages has made it more assertive than its partner and enabled it to manipulate reality, shutting down the right’s holistic view of the world – deeming it quaint and out of touch with a reality created by the right. Its penchant for self-consistency entails that it finds it difficult to accept that it might be wrong, a common syndrome in mediation. These factors explain the optimistic over-confidence encountered repeatedly in the mediation room (from both parties and advisers) which provides a challenge to mediators and other dispute resolvers.

It is not possible to depict definitively how emerging knowledge bases in psychology and neuro-science can be given effect at the mediation table. It is no easy task, for example, for mediators to identify parties’ cognitive and social biases accurately as these operate instinctively, without even the relevant party’s conscious awareness, and the other party and mediator may well remain unaware of them. Nonetheless all knowledge about human decision-making is potentially relevant in mediation and provides a tentative foundation for understanding the dynamics of parties’ negative dispositions and behaviours and what might be done about them. Moreover, while the biases may induce a lack of rationality to mediation decision-making, there is some degree of predictability in the different forms of irrationality.

John Wade used the metaphor of the mediator’s tool-box of interventions, implying that mediators will not always be able to adopt standardised procedures and linear logic but may have to be reactive, responsive and instinctive in using different tools in the process. The National Mediator Accreditation System provides some guidance on mediator responsibilities in relation to conflict, negotiation and culture but this is of only limited proportions. Psychology and neuro-science are definitely new tools for the mediator’s tool-box.

John Wade used the metaphor of the mediator’s tool-box of interventions, implying that mediators will not always be able to adopt standardised procedures and linear logic but may have to be reactive, responsive and instinctive in using different tools in the process. The National Mediator Accreditation System provides some guidance on mediator responsibilities in relation to conflict, negotiation and culture but this is of only limited proportions. Psychology and neuro-science are definitely new tools for the mediator’s tool-box.

In lockdown communications we don’t have mediators with us thinking about all these complexities to communications. So we need to enact our dispute resolution agency and be aware of the psychological and neuro-science elements at play. In the next post we consider some of the specific psychological elements we can be aware, and take account, of in our lockdown communications.

Tomorrow’s Blog: Lockdown Dispute Resolution 101 #23: Effective communication strategies in lockdown – dispute resolution psychology basics: Part 2

Acknowledgements

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Rachael Field, Mediation in Australia (LexisNexis, 2018) paras 6.72-6.99.

Brain image 1: Harley Therapy

Confirmation bias image 1: Medium

Neuroscience image 1: Nature

Prof Ian McGilchrist image: Byron Clinic

Prof John Wade image: Mediate.com

In acting as an agent of reality, a key strategy to help the parties consider whether a settlement or solution is realistic and viable is to question them about what the proposed solution would look like in operation in the context of their lives outside mediation, helping them to cogently and realistically think through the risks, options and choices available to them.

In acting as an agent of reality, a key strategy to help the parties consider whether a settlement or solution is realistic and viable is to question them about what the proposed solution would look like in operation in the context of their lives outside mediation, helping them to cogently and realistically think through the risks, options and choices available to them.

Some of the content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.57-6.58 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you – Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities. The post also includes content from Laurence Boulle and Rachael Field, Mediation in Australia (LexisNexis, 2018) 104-5.

Some of the content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.57-6.58 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you – Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities. The post also includes content from Laurence Boulle and Rachael Field, Mediation in Australia (LexisNexis, 2018) 104-5.

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

Good summarising requires a range of micro-skills, such as retaining important information, recalling it and condensing it. It is always a selective process in that in a mediation, mediators pick up on positive progress to date and present it in a constructive and concise statement. It is also selective in that mediators pick up only on what is useful for the communications – not everything gets summarised. The reason why mediators are selective in enacting the summarising process is that selectivity allows them to create a positive and encouraging basis for the parties to move forward with their negotiations. However, summaries also need to be balanced in the sense that they deal fairly with what each side has said.

Good summarising requires a range of micro-skills, such as retaining important information, recalling it and condensing it. It is always a selective process in that in a mediation, mediators pick up on positive progress to date and present it in a constructive and concise statement. It is also selective in that mediators pick up only on what is useful for the communications – not everything gets summarised. The reason why mediators are selective in enacting the summarising process is that selectivity allows them to create a positive and encouraging basis for the parties to move forward with their negotiations. However, summaries also need to be balanced in the sense that they deal fairly with what each side has said.

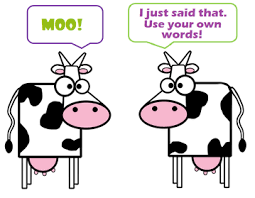

In a mediation, mediators ensure that paraphrasing is done in an even-handed way so that both the parties’ communications are paraphrased. In this way, it can be used to set up a pattern of direct communication between parties, and it can break what Australian mediation legends Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney have called the ‘Oh but’, ‘Yes but’ pattern of communication: ‘Oh but I didn’t understand that’s what you wanted.’ ‘Yes but I had told you only two days before …’. ‘Oh but I called and texted you …’ ‘Yes but …’ (2014: 250). However, if this is the only way of keeping parties communicating constructively it can quickly become strained and artificial.

In a mediation, mediators ensure that paraphrasing is done in an even-handed way so that both the parties’ communications are paraphrased. In this way, it can be used to set up a pattern of direct communication between parties, and it can break what Australian mediation legends Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney have called the ‘Oh but’, ‘Yes but’ pattern of communication: ‘Oh but I didn’t understand that’s what you wanted.’ ‘Yes but I had told you only two days before …’. ‘Oh but I called and texted you …’ ‘Yes but …’ (2014: 250). However, if this is the only way of keeping parties communicating constructively it can quickly become strained and artificial. Generally, reiteration is one of the tools in the mediator’s toolbox which can be used in all situations in which parties are talking past each other and not picking up on important messages.

Generally, reiteration is one of the tools in the mediator’s toolbox which can be used in all situations in which parties are talking past each other and not picking up on important messages. See also: Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney,

See also: Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.47-6.54 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities.

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.47-6.54 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities.

When mediators reframe, they are engaging in a translation exercise through which they change the communication by moving it from one type of language to another. The intention is that the second language version is more palatable to the parties and more conducive to collaborative problem-solving.

When mediators reframe, they are engaging in a translation exercise through which they change the communication by moving it from one type of language to another. The intention is that the second language version is more palatable to the parties and more conducive to collaborative problem-solving.

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

As human beings, we all have a basic capacity for empathy, and we are also socialised to extend that capacity because in every culture, even though empathy may manifest in diverse ways, some level of empathy is important to the quality of human relations. In order to harness the communication benefits of empathy, we must be present in our communications with others, paying attention and prepared to engage and connect. Listening empathically means that we are focused on what the other person is saying, observing, feeling, needing and requesting.

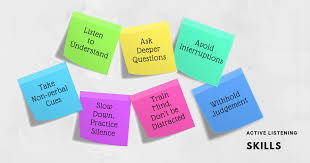

As human beings, we all have a basic capacity for empathy, and we are also socialised to extend that capacity because in every culture, even though empathy may manifest in diverse ways, some level of empathy is important to the quality of human relations. In order to harness the communication benefits of empathy, we must be present in our communications with others, paying attention and prepared to engage and connect. Listening empathically means that we are focused on what the other person is saying, observing, feeling, needing and requesting. This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of

This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of  Effective listening

Effective listening

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,  See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

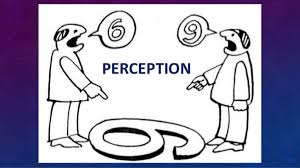

Perceptions and subjectivity are therefore important factors in conflict and disputes. However, conflict situations with the potential to turn into concrete disputes may not do so because they exist only in the perception of one or both parties and not in actual reality – for example two employees perceive themselves to be competitive rivals for one position whereas neither is realistically in line for it. This can be referred to as pseudo conflict in which parties’ perceptions or expectations are false or based on incorrect fears or unjustified apprehensions. False conflicts are based on stereotypes about others in terms of their personal or group attributes, for example about management or unions, or about refugees and security officials, and these can be accentuated by continuing ignorance or withholding of information, or by rumours, confirmation biases and wilful blindness. There may be little basis to the conflict in reality but it is played out by one or more parties as if there was. With both pseudo conflict and false conflict, the sharing of correct information, the provision of an explanation, or righting a misperception or a misunderstanding can help to resolve the situation.

Perceptions and subjectivity are therefore important factors in conflict and disputes. However, conflict situations with the potential to turn into concrete disputes may not do so because they exist only in the perception of one or both parties and not in actual reality – for example two employees perceive themselves to be competitive rivals for one position whereas neither is realistically in line for it. This can be referred to as pseudo conflict in which parties’ perceptions or expectations are false or based on incorrect fears or unjustified apprehensions. False conflicts are based on stereotypes about others in terms of their personal or group attributes, for example about management or unions, or about refugees and security officials, and these can be accentuated by continuing ignorance or withholding of information, or by rumours, confirmation biases and wilful blindness. There may be little basis to the conflict in reality but it is played out by one or more parties as if there was. With both pseudo conflict and false conflict, the sharing of correct information, the provision of an explanation, or righting a misperception or a misunderstanding can help to resolve the situation.