Robert Angyal SC has posted a detailed and thought provoking response to the most recent ADR Research Network Blog Post on the National ADR Principles – so I have posted it here on Robert’s behalf. Many thanks Robert for your engagement with the Blog! And thanks to Vesna and Teresa who also posted comments! Keep the comments coming!

The post asks, “Is ADR essentially about the provision of a process which is fair, or an outcome which is fair, or both?” There are several problems with the question itself.

First, what is meant by “ADR”? To this writer, ADR means going to court because the primary dispute resolution process, mediation, has not resulted in settlement of the underlying dispute. This is because mediation is ubiquitious in modern Australian civil dispute resolution. I think, however, the author of the question meant something different by “ADR”.

The second problem with the question is this: Is it a question which calls for a description of how mediation actually is practised in Australia and an assessment whether it leads to fair results – that is, does it call for a descriptive answer? Or is it a question about how mediation should be practised in Australia – that is, does it call for a normative answer based on moral norms about how the practise of mediation should be conducted?

If the question is a normative one, it leads to two more questions: First, who laid down these moral norms, and by what authority did they do so? Second, and equally fundamental, why should we assess mediation by moral norms at all? We don’t normally assess the practice of civil dispute resolution by moral norms; no, we assess it by criteria such as efficiency, cost, access, speed, compliance with the rules of natural justice, and so on. Why should mediation be different?

The third problem with the question “Is mediation about a fair process or about a fair outcome?” is the biggest one: It assumes that mediation is fair (descriptive) or should be fair (normative). It doesn’t admit the possibility that mediation might not be about fairness in either sense. You’re saying, I know, “Hang on, of course mediation is meant to be fair; that’s why people do it rather than going to court.”

I have two sorts of bad news for you. The first bad news is that in any particular case, the question “Is mediation fair?” is unanswerable, for lots of reasons. The biggest reason is that the parties will disagree about what’s fair. That’s why they’re having a mediation in the first place. If they could agree about what’s fair, they wouldn’t need a mediation or a mediator. Given this and the fact that mediations always are conducted in private, even if a third party could find out the outcome of a particular mediation, how could they form an opinion as to whether it’s fair?

The second piece of bad news is that my empirical observation, based on mediating for 30 years, is that parties to a mediation aren’t participating in the mediation because they think it’s a fair process and/or one that will lead to a fair outcome. They’re mediating because, and mediation works because, they are worried stiff about continuing the underlying legal proceedings. They are worried because litigation is very expensive, very destructive of relationships, very time-consuming and drawn-out and – most scary of all – very unpredictable as to result, with costs usually following the very unpredictable result. Losing means you get nothing out of the proceedings except the obligation to pay not only your costs but also the winner’s costs.

So the reason they are mediating is to mitigate the huge risks inherent in conducting civil litigation. To put it bluntly: Many parties to civil litigation can’t afford to lose – but they have no way of knowing with any certainty whether they will lose or win. They are looking for a way to avoid taking the risk of losing.

Some parties are even worse off: They can’t afford to run the legal proceedings to judgment but neither can they afford to call a halt to the proceedings, because a party who discontinues proceedings almost always has to pay the costs to date of the other side. They are caught in a costs trap, from which they need to find an escape. Mediation offers hope of an escape.

What this means in practice is that fairness is not a concept that’s relevant in mediation. Typically, a party will settle at mediation if the settlement being offered to them is better than the risk-laden nightmare of continuing the underlying legal proceedings. That’s the calculus that drives mediations towards settlement in my experience. It means that a lot of cases settle on terms that might shock outsiders: Plaintiffs sacrifice their causes of action and claims for damages in exchange for being released from the obligation to pay the defendant’s costs. Defendants who could defeat the plaintiff’s claim at trial pay plaintiffs to go away – because, the defendant knows, it will cost a lot of money to defeat the plaintiff’s claim but those costs won’t be recoverable from the plaintiff. So, as long as the case can be settled for less than the defendant’s irrecoverable costs, it’s cheaper to settle than to win the case. Fairness doesn’t enter the picture.

So can we abandon questions about fairness in mediation as irrelevant? They only distract attention from difficult and important questions about mediation, such as:

- Why does mediation work?

- How does mediation work?

- How can I effectively represent a client at mediation?

- What are the ethical limits on my advocacy at mediation?

Robert Angyal SC

4 July 2021

Another interesting post from Robert is in the wings – so keep an eye out for that one!

Photo Credit:

Photo Credit:  The reality of the stressful nature of life in lockdown as a result of COVID-19 is that the quality of our communications and negotiations is under pressure. We need to harness our dispute resolution agency, and employ positive strategies and methods from the art of mediation, in order to ensure we do our best to prevent, manage and resolve disputes. We also need to practice self-management, for example by building our resilience skills, so that we protect our psychological well-being and ensure we have the right attitudes and energies for lockdown living.

The reality of the stressful nature of life in lockdown as a result of COVID-19 is that the quality of our communications and negotiations is under pressure. We need to harness our dispute resolution agency, and employ positive strategies and methods from the art of mediation, in order to ensure we do our best to prevent, manage and resolve disputes. We also need to practice self-management, for example by building our resilience skills, so that we protect our psychological well-being and ensure we have the right attitudes and energies for lockdown living.

Thank you: This series of posts was only possible through the collegial generosity of ADR Research Network members. Thank you to Professors Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander for very kindly allowing me to use and adapt Chapter 6 of their

Thank you: This series of posts was only possible through the collegial generosity of ADR Research Network members. Thank you to Professors Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander for very kindly allowing me to use and adapt Chapter 6 of their

Understanding stress

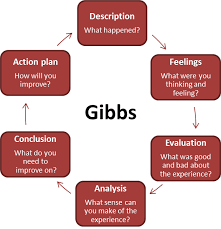

Understanding stress Intentionally managing our stress in lockdown involves quite practical, common sense approaches and strategies around building our resilience. Resilience is a capacity to cope well under pressure, as well as an ability to respond and endure in situations of adversity. In other words, resilience skills help us to manage and prevent stress.

Intentionally managing our stress in lockdown involves quite practical, common sense approaches and strategies around building our resilience. Resilience is a capacity to cope well under pressure, as well as an ability to respond and endure in situations of adversity. In other words, resilience skills help us to manage and prevent stress.

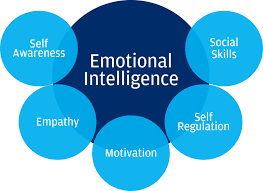

Simply put, emotional intelligence is the intelligent use of emotions. This requires an awareness of our emotions and an ability to use that awareness to beneficially aid our thinking and behaviour. Emotional intelligence informs our capacity to perceive emotions, assimilate emotion-related feelings, understand the information of those emotions, and manage them.

Simply put, emotional intelligence is the intelligent use of emotions. This requires an awareness of our emotions and an ability to use that awareness to beneficially aid our thinking and behaviour. Emotional intelligence informs our capacity to perceive emotions, assimilate emotion-related feelings, understand the information of those emotions, and manage them. Emotional contagion is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the ‘catchability’ or contagiousness of emotions. For example, if Rachael is in a particularly happy mood, this mood may end up rubbing off on Anna and Anna may subsequently begin to feel happier. Anna might then ‘infect’ others with her happiness. Emotional contagion ‘refers to the tendency to catch (experience/express) another person’s emotions’ (Kimura, Daibo and Yogo, 2008, 27).

Emotional contagion is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the ‘catchability’ or contagiousness of emotions. For example, if Rachael is in a particularly happy mood, this mood may end up rubbing off on Anna and Anna may subsequently begin to feel happier. Anna might then ‘infect’ others with her happiness. Emotional contagion ‘refers to the tendency to catch (experience/express) another person’s emotions’ (Kimura, Daibo and Yogo, 2008, 27). Emotional flooding occurs when an individual becomes swamped by emotions. Biologically, intense emotional experience can affect the way the brain works. Information exchange to the neo-cortex is inhibited, with the result that people find it difficult to think in cognitively complex ways and to function properly. This might sound like a really extreme and rare occurrence, but it actually happens to people surprisingly frequently.

Emotional flooding occurs when an individual becomes swamped by emotions. Biologically, intense emotional experience can affect the way the brain works. Information exchange to the neo-cortex is inhibited, with the result that people find it difficult to think in cognitively complex ways and to function properly. This might sound like a really extreme and rare occurrence, but it actually happens to people surprisingly frequently. The concepts of transference and countertransference have their origin in the work of Sigmund Freud and his focus on psychoanalysis/psychodynamic theory. Freud was a famous psychologist for many reasons, although when most people think about Freud, they often think about beards, couches, and unconscious and sexually repressed thoughts and behaviour. These images are all accurate to a certain degree. As it turns out, one of the reasons why Freud used ‘the couch’ when treating patients related to the notion of countertransference: ‘Freud frankly admitted that he used this arrangement inherited from the days of hypnosis, because he did not like “to be stared at”; thus, it served him as a protection in the transferencecountertransference duel’ (Benedek, 1953, 202).

The concepts of transference and countertransference have their origin in the work of Sigmund Freud and his focus on psychoanalysis/psychodynamic theory. Freud was a famous psychologist for many reasons, although when most people think about Freud, they often think about beards, couches, and unconscious and sexually repressed thoughts and behaviour. These images are all accurate to a certain degree. As it turns out, one of the reasons why Freud used ‘the couch’ when treating patients related to the notion of countertransference: ‘Freud frankly admitted that he used this arrangement inherited from the days of hypnosis, because he did not like “to be stared at”; thus, it served him as a protection in the transferencecountertransference duel’ (Benedek, 1953, 202). The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Rachael Field, James Duffy and Anna Huggins,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Rachael Field, James Duffy and Anna Huggins,