By Eunice Chua (CEO, FIDReC) and Rachel Lim (Intern, FIDReC)

The context of consumer financial disputes

Tom went on an overseas holiday with his friends, and they went out to a pub on their last night. They drank till the early hours of the morning. Tom was in a celebratory mood and paid for everyone’s drinks with his credit card. He and his friends left for their hotel at 3am. Tom only woke up at 2pm the next day and hurriedly rushed to catch his flight back to Singapore. After he arrived in Singapore, he realised that one of his credit cards was missing. He immediately made a police report and called the bank to report the loss. In the meantime, someone had already gone on a shopping spree with Tom’s credit card and bought various items to the tune of S$7,000. The bank billed Tom for this amount, but Tom disagreed.

Sally purchased a hospital and surgical insurance policy from her brother-in-law a few years ago. Because she trusted him, she left him to fill out all the details and signed where he told her to. Her brother-in-law went through with Sally a list of questions at the end of the proposal form and the terms and conditions of the policy, but Sally did not pay much attention at the time. Unfortunately, Sally was diagnosed with a tumour on her breast. She was admitted to the hospital for surgery. After her surgery and hospital stay, Sally submitted an insurance claim. As part of its usual process, the insurer contacted Sally’s doctor to request information on Sally’s condition. It was then that the insurer found out that Sally had a history of diabetes. Sally had failed to disclose this information in the insurance proposal form. The insurer told Sally they would void her policy due to her failure to disclose her diabetes.

These scenarios reflect real cases that consumers bring to the Financial Industry Disputes Resolution Centre (FIDReC) in Singapore. FIDReC was established in August 2025 as an initiative from the financial industry to provide an accessible platform for financial institutions to resolve customer complaints in an effective, amicable, and fair way. Accordingly, filing a claim at FIDReC is free for consumers. The process is simple, with mediation being deployed first and adjudication being offered as an option only if there is no settlement at mediation.

The FIDReC approach to dispute resolution

Five core principles shape FIDReC’s approach to dispute resolution: accessibility, independence, effectiveness, accountability, and fairness. Most of these are self-explanatory but it is worth saying more about fairness.

The FIDReC process is designed in a way that recognises the inherent imbalance of power between an individual consumer and a financial institution and seeks to address that balance in a fair manner.

First, designated financial institutions are required by regulation to subscribe to FIDReC and participate in its process. This ensures that consumers will have the opportunity to bring their claims to FIDReC and have them answered. Second, only consumers may bring claims at FIDReC. They may do so without any filing fee and the claims filing is done online. This promotes accessibility even for those that are not well off. Third, mediators are staff of FIDReC who are well versed with the regulations governing the financial industry as well as industry standards and expectations. Whilst maintaining their impartiality, they may make suggestions to parties and provide information to help them in their decision-making. This promotes a fairer playing field especially for more vulnerable consumers. Should there be any settlement, the mediator gives parties time to consider before they sign on any agreement. This reduces the risk of any pressure to settle. Finally, the process is driven by the consumer who can opt to proceed to adjudication if they are not satisfied with the mediation outcome. They pay a nominal fee of S$50 per claim for an independent adjudicator to review their submissions, conduct a hearing and decide on whether they have a valid claim. Subject to approval by the adjudicator, the consumer can choose the mode of adjudication – in-person, online or based on documents review. The adjudication outcome binds only the financial institution who must enter a settlement in the terms of any award made by the adjudicator if the consumer so accepts. If the consumer disagrees with the adjudicator’s decision, the consumer’s legal rights are not affected, and they may still pursue a case in court or in other avenues.

Mediation first

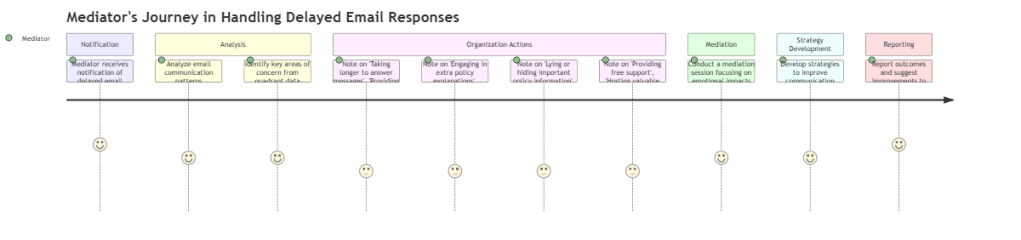

More than 80% of claims filed at FIDReC are resolved at mediation, demonstrating the value of mediation to bring about closure in consumer financial disputes. Mediation is a resource-intensive activity as one mediator is assigned to each case and follows that case through from beginning to end. The mediator will need time to understand and clarify the claim that the consumer is bringing as well as to review the financial institution’s investigation report. It is hard work and “heart work” for the mediator as consumers may come with varying expectations and intense emotions. It is also a journey that could take place over months. Nevertheless, the benefits of mediation are clear.

First, mediation allows the parties to tell their stories and be directly involved in shaping a way forward. The information-exchange that takes place during mediation educates the parties on their rights and responsibilities and equips them with knowledge. They may also be able to negotiate better with each other in a confidential setting with the support of a mediator.

In Tom’s case, mediation allowed Tom to acknowledge that he could have been more careful to safeguard his credit card while putting forward the efforts he did take to report the loss of his card when he discovered it. The bank was able to share about the dispute resolution process it had in place for credit card disputes and its considerations. Nevertheless, the bank was not limited to considering the legalities of the claim and could also account for Tom’s history with them. In the end, the bank made a goodwill offer to absorb twenty percent of Tom’s losses, which Tom accepted.

Second, mediation outcomes can be creative solutions that meet the interests of both parties. Such outcomes may not be possible through the court process.

During the mediation in Sally’s case, the insurer showed she had answered “no” to having diabetes in the proposal form and pointed out a warning on the form in red that failure to disclose material information could lead to claims being rejected or the policy being voided. Sally explained that her diabetes was mild, well-managed, and unrelated to her breast tumour. The mediator suggested she submit a medical report on her diabetes condition to allow the insurer to review its assessment. After considering the additional medical report, the insurer agreed—on a goodwill basis—not to void the policy but to adjust the policy terms. Although Sally’s claim was not reimbursed due to the non-disclosure, Sally accepted the outcome because it was important for her to keep her insurance coverage.

Third, relative to adjudication and going to court, mediation helps to save time and costs. Most cases at FIDReC are closed within six months from the date they are accepted for handling. Cases resolved through mediation usually close within three months.

Why not something different?

FIDReC is certainly not the only model existing in the world that deals specifically with consumer financial disputes. The Australian Financial Complaints Authority (“AFCA”) shows another way forward with its own model of dispute resolution that combines conciliation with a preliminary assessment followed by a binding determination (if the consumer accepts it).

The key difference between the two is that AFCA is a statutory body equipped with a broad fairness jurisdiction and powers to order more than just financial compensation (AFCA can even order an apology as a remedy!). This imbues AFCA with more authority whereas FIDReC relies on the cooperation of the parties to promote settlement at mediation, with adjudicators limited to ordering financial compensation. The local context is also a crucial factor. AFCA supports more than 26 million people spread across an entire continent. FIDReC supports a population of about 6 million in a small island state 0.009% the size of Australia. Even as FIDReC can offer a personalised high human touch approach including the option of in-person mediation meetings and adjudication hearings, this may not be feasible in Australia where conciliation is conducted through a telephone conference and preliminary evaluations and determinations are based on a documentary review.

The scope of work of AFCA and FIDReC is different too. Although the focus is consumer financial disputes, AFCA has a much higher claim limit exceeding AUD1 million. FIDReC does not impose any claim limit during mediation but has a limit of S$150,000 per claim for adjudication. This has consequences for process design. For example, AFCA permits external legal representation given that high value claims can have greater complexity, whereas FIDReC does not as it prioritises a more informal and low-cost approach. AFCA relies on more evaluative modes of dispute resolution like conciliation, preliminary assessment, and determination. FIDReC primarily relies on mediation with adjudication being resorted to less than 20% of the time.

FIDReC’s mediation-first model has proven to be effective within Singapore’s context. By focusing on amicable resolutions and keeping processes informal, FIDReC ensures that everyday consumers can navigate financial disputes without being overwhelmed and can continue their relationships with their financial institutions.

That said, we recognise that the financial landscape is constantly evolving. As products grow more complex and consumer expectations shift, FIDReC remains open to refining its approach. Be it integrating new tools, expanding our jurisdiction, or adapting elements from other models like AFCA’s, we are committed to staying relevant and responsive whilst being guided by our core principles.

Eunice Chua is the FIDReC CEO overseeing mediation and adjudication of consumer financial disputes in Singapore. Before that, Eunice was Assistant Professor at the Singapore Management University, specializing in alternative dispute resolution, evidence, and procedure. She remains a Research Fellow at the Singapore International Dispute Resolution Academy. Eunice was formerly Justices’ Law Clerk and Assistant Registrar of the Singapore Supreme Court, where she concurrently held appointments as Magistrate of the State Courts and Assistant Director of the Singapore Mediation Centre. She was also the founding Deputy CEO of the Singapore International Mediation Centre.

Rachel Lim is an aspiring Law and Finance student and a proud graduate of Hwa Chong Institution. With a deep interest in Economics and meaningful involvement in grassroots organisations, she has developed a quiet yet insightful appreciation for how money moves through society. In this debut work, Rachel explores the growing issue of scams in Singapore’s payment systems, emphasising the importance of awareness and financial mindfulness. Through compassionate storytelling and clear guidance, she hopes to shed light on the support systems available to victims, offering a hopeful and empowering message for those navigating today’s complex financial landscape.