This article is submitted by Professor Laurence Boulle, eminent professor and teacher of dispute resolution at universities throughout Europe, Africa, North America and Australasia.

Perspectives

Politics and government are complicated affairs. So are many forms of dispute resolution (DR). The two social systems have different premises: DR is about building a consensus that did not previously exist, while politics is about competing for the levers of state power. There are, however, exceptions and qualifications to the dominant operational mode of each pursuit, and inevitable similarities between them. This piece examines the views and insights of a major Australian politician from a DR perspective.

Malcolm Turnbull’s book, A Bigger Picture (Hardie Grant Books, 2020), received a hostile reception in the conservative media – which had in turn been censured in the book. A prime minister’s autobiography, however, is an important potential contribution to social understanding – it emanates from the source, so to speak. This work is revelatory, analytical, polemical and sometimes confronting. Prospective readers also require a health warning – the work is just shy of 700 pages in length and could fell an intruder not maintaining their physical distance.

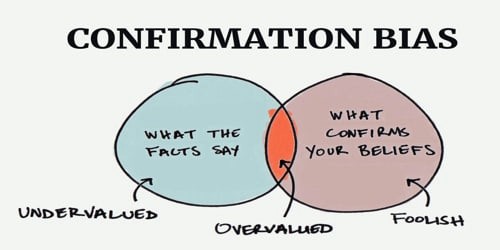

Diligent dispute resolvers examine the world in search for evidence relevant to their own extensive knowledge base. These days this involves a focus on personal and institutional biases – for example confirmation biases, the availability heuristic, the hindsight bias and other cognitive and social patterns. This mediator preoccupation annoys friends and family but focuses our inquisitive instincts in the way we observe political discourse, popular culture or classical literature. Biases and heuristics abound in all autobiographies, as they do in DR writers.

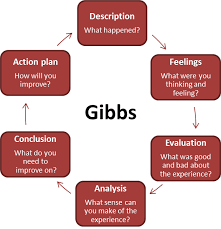

In taking up this book, I was keen to see how the author (albeit not NMAS-accredited) commented on, or self-assessed, his role as a conflict manager, negotiator, conciliator and dispute resolver. Here the work provides much to ponder, analyse and evaluate in the course of its compelling narrative.

Politics

We know that party politics in parliamentary systems of government, as in traditional common law systems, is intensely partisan and adversarial in nature. We have also known, though not quite as obviously, that adversarialism can sometimes be as intense within a political party as it is across party lines. These propensities are confirmed in the Turnbull memoirs through frequent references to policy, personality and politics being played out as much on intra-party as on inter-party lines. This is a fine reminder for dispute resolvers not to not overlook the presence of hawks, doves and moderates (John Wade’s enduring terms) within negotiating teams, and sometimes also among each team’s stakeholders outside the DR room.

In terms of agents external to formal political processes, Mr Turnbull ventures an assessment that will be accepted by some and rejected by others – such is the tribal nature of current Australian politics. In the author’s assessment the right-wing media – print, electronic, televised – has assumed the status of a ‘political party’ on issues such as energy, refugees and the environment. They lack, however, responsibilities associated with electoral and other accountability systems designed to monitor and discipline those within the formal political processes.

This is a significant theme in the work and is a reminder for those working with disputes, whether small or large in size and consequence, that external stakeholders can be deal-makers or deal-breakers and need to be included appropriately in the respective process. This is easy neither in politics nor in mediation but could be substantial in achieving settlements – and maintaining them. This task is potentially easier for mediators than for prime ministers.

Power

The former PM is unrepentant in admitting that he was involved in ‘many political punch-ups … never being shy of confrontation’. This suggests he was not reluctant to exercise his dispatchable power in politics, and also in business.

Power is also a major factor in international relations. Australia’s long involvement in middle eastern countries has always been a power-centred intervention, based on military capability, powerful allies and political choices, and it was strongly endorsed by the former PM.

Some reflection here, with his own considerable power of intellect, might have caused the former PM to examine Australia’s past and current roles more critically. After all, the power invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq have been regarded as serious failures in many forums, including in the US. Here politics has the same problem of the sunk costs bias often found in DR contexts: it induces parties to continue the ‘good fight’ because of what they have already lost in the past as opposed to making decisions in terms of what they might gain in the future. In mediation settings, a potential counter to the sunk cost bias is the reality-testing function of interveners, something less easy to broker in international relations.

Mr Turnbull was, on occasions, able to use power interventions of a less militant kind. He pushed, for example, for the regulation of export controls on Australian gas when all prior attempts at negotiations had failed. This, despite regulation not complying with dominant ideologies relating to the role of markets. Necessity, as we know, can the mother of invention, though the confirmation bias is always potentially present in one person’s account of social developments.

Power plays were also evident in the leadership challenges within Mr Turnbull’s Liberal Party. A leadership challenge is a process in which intra-party power dynamics determine outcomes definitively, without mediator-like nuances of options, concessions and mutual gains. Here the former PM was twice a winner and twice a loser, the force of numbers in each case dictating loss and gain, without any middle ground.

Dispute resolvers understand the place of power interventions in appropriate conflict circumstances, but usually only after preventative, interest-based and rights-focused interventions have failed. ‘Branch-stacking’, openly admitted to in the book, is a peculiarly power-driven political strategy within parties, but it has potential DR analogues: enlarging a client’s professional adviser team, strategically lacking settlement authority, bringing intentional ambiguities into offers and making irrevocable commitments elsewhere (and other ‘tricks’ of negotiation well documented by Hal Abrahamson). The tricks, in politics and DR, may lead to short-term gains but cause long-lasting damage to relations, credibility and the legitimacy of respective institutions.

Rights

As a lawyer Mr Turnbull was no stranger to asserting clients’ rights and remedies in dispute contexts. This is epitomised by the Spycatcher case in which he and his wife Lucy Turnbull took on, and defeated, the might of the British state in the Australian courts. This was not the occasion for compromise, despite some potential attractions for the client. However while strong legal research and assiduous advocacy are important sources of power, court outcomes are ultimately based on legal rights, duties and remedies.

While often regarded as a consummate barrister, Mr Turnbull in fact spent a relatively short time at the Sydney bar prosecuting, or defending, rights-based outcomes for clients. The gravitational pull for him was towards banking, business and investment where power and interests are more likely to be the dominant intervention modes. These are also the theatres of intense negotiation and bargaining.

Negotiation

Negotiation, in the ideal world, is less about power and rights and more about commercial, personal and national interests. As regards Donald Trump, author of a negotiation text, the former PM engaged with him on at least two substantive matters: the ‘swap’ of Australia’s off-shore refugees for other refugees in the US and the lifting of tariffs on our steel exports to that country.

Both of these negotiations are framed in terms of ‘trade-offs’ for mutual gain, despite one involving desperate humans and the other inanimate steel (though the jobs issue was also relevant in relation to exports). Mr Turnbull claims, with seeming justification, to have trumped the negotiator-in-chief in each situation. In cryptic form the following lessons were adduced from the negotiation experiences:

- · Do not be sycophantic with bullies, as leaders of some governments are – rather be up-front, frank and stand up to them from the start.

- · Take pains to establish good personal and working relations before commencing negotiations on the substantive issues.

- · Focus on interests and needs, in particular those of the other side, as a basis for problem-solving and settling differences.

However self-serving this assessment might be, the claimed lessons do satisfy DR principles on dealing with high conflict personalities – using relational methods of communication, introducing interest-based methods and deploying mutual gains strategies. The accounts from the political front suggest that dispute resolvers may benefit from discovering more about the intricacies of negotiations in domestic politics and international relations.

Institutions

The government of the former PM was responsible for an institutional innovation in Australian DR, namely the establishment of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA). It is both a dispute prevention system and a forum through which clients can potentially resolve disputes with banks and other financial institutions.

Whatever its strengths and shortcomings, which will be revealed in due course, the AFCA is a classic form of institutionalised DR and access to justice. The banking enquiry had established that the use of power and control by financial institutions was detrimental to many account holders and numerous other clients. They are now afforded some statutory rights and remedies to mitigate the power dynamics of the relationship. Ironically, many DR processes and institutions have over the years been introduced through legislation in adversarial political institutions.

The former PM, however, overlooks one of the contentious features of international economic treaties, namely the investor-state dispute systems (ISDS) they routinely establish. While Mr Turnbull long championed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, adroitly reframed by the Canadian PM to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, he elides the controversial ISDS which it establishes. In general terms ISDS has potential benefits for international investing corporations at the cost of national sovereignty, parliamentary democracy and domestic regulation (remember Australia’s Plain Packaging case?).

Treaties are archetypal conflict prevention instruments, the equivalent in international relations of contracts in commercial situations. Procedurally they create systems for dealing with trade and investment conflicts, substantively they establish rights, duties and remedies, and societally they shift risks and create potential winners and losers in different economic sectors.

Here the former PM’s enthusiasm for freedom of trade and investment overlooks the power dynamics which prevail in negotiating such treaties and the inevitable losses they portend for at least some enterprises, for example manufacturers of substitutable imports. The ISDS systems, in particular, are not favoured in many jurisdictions forced to acquiesce to them because of their powerlessness, relative to the dominant treaty states. While treaties reflect, in different ways member states’ respective commercial interests and create legal rights and obligations, they are founded on confidential unfacilitated negotiations with all the power determinants that might conceal.

Science

The current pandemic highlights a significant cultural change in relation to the public influence of science and scientists. Presently national and sub-national governments in many jurisdictions are predicating their Covid-19 policies on the latest medical and scientific evidence.

This commendable practice has been entirely lacking in climate change politics. Mr Turnbull is appropriately critical of the war on science waged by former PM Abbott and others and he cites the adage that everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not to their own facts. This is a sound principle, but susceptible drowning in the current ocean of ‘fake’ and ‘alternative’ facts.

Investigative agencies can and do examine relevant factual circumstances and are important institutions in the DR matrix. The Turnbull government long resisted an inquiry into the banking sector and it was only when under immense pressure that he was forced to appoint the Hayne Banking Commission. Nonetheless he is somewhat dismissive of its outcomes, despite admitting that he made a ‘political mistake’ in not constituting it earlier. An alternative view is that the Commission’s recommendations and the banks’ responses could be important factors in clients enforcing their rights and remedies in the face of egregious behaviour by powerful banks.

A federal Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) is another agency which could investigate, prevent and manage disputes, and above all, bring transparency to the darker reaches of government. The most generous comment here would be that, like crowded court lists, there was too much to do in too limited a time to enable Mr Turnbull to manage this reform during his time in office.

He is, however, by no means oblivious to the advantages of transparency on matters of public interest. He is, for example, surprisingly critical of the Church’s stance on openness in relation to school funding, evident in his negotiations with the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney. Here the partial transparency of politics contrasts with the mostly confidential nature of DR processes such as arbitration and conciliation. In a bigger picture, facts and science can be easily trumped by values in the fiery crucible of politics.

Values

‘Value’ disputes are the bane of mediators’ lives. Here the autobiographer provides an interesting insight into respective politicians’ attitudes towards coal, carbon and climate change. After a heated carbon dispute among colleagues, one of Mr Turnbull’s own ministers, who had sat through the adversarial confrontation, indicated to him that reason would not prevail on climate because denialism is a matter of ‘religious belief’. It is difficult to negotiate over religious, and other personal, convictions, as dispute resolvers well know.

Despite long-standing credentials in relation to the environment the former PM was on the losing side of the coal conflict and a national energy policy – within his own party. However while the author burnishes his own environmental credentials, he manages only a passing reference to one of the biggest climate conflicts of the age, namely in relation to the Adani mining development in Queensland. This gives the impression of being the availability heuristic – only in reverse.

There is a current tendency in all adversarial systems, whether in politics, law or dispute resolution, for ‘beliefs’ to trump rationality and for ‘emotions’ to trump reason. Here there is sad irony in the fact, alluded to in the book, that there was once bipartisan support in Australia for reducing emissions, yet this is currently a battleground for tribal warfare – with high emotion and limited reliance on the science. DR practitioners know too well that if commercial deals are not sealed after productive momentum ‘on the day’ they may be refought more intensely the following morning – unfortunately said practitioners were not engaged when the bipartisan support was present and willing and the momentum has now been entirely lost.

Lessons

The biography provides some droll take-aways for dispute resolvers, for example to ‘leaven … aggression with a touch of humour’, though less so in the wry observation that in politics there is ‘no shortage of bad options’. The roles of humour, and occasionally wryness, are much analysed in the DR literature and practitioners would concur with the author’s cryptic suggestion.

In terms of language and communication the author condemns the ‘exaggeration or oversimplification’ pervasive in political discourse – and which is also seen in some DR contexts. Mr Turnbull’s aversion to the ‘political slanging match’ would receive acclaim in most Australian households. However tribal politics leads to simplistic slogans in every corner – in Mr Turnbull’s case the well-worn mantra of ‘jobs and growth’.

Politicians from all sides are also prominent framers and reframers of language and terms (or spinners and tricksters), for example in relation to the ‘Mediscare’ and ‘retiree tax’. They do not provide good role models in these techniques for DR situations where beneficial reframing is one of the mediator’s quintessential roles. Pejorative framing leads to negative priming, which leads to simplistic claims and defences whether in litigation or mediation. Poor framing in politics and dispute resolution leads to reductionist as opposed to expansionary thinking

As regards broader justice issues, there is some foreboding for mediators in the author’s reference to the Athenian saying, ‘Justice is found only between equals in power, as to the rest the strong do as they will and the weak suffer as they must’. Here there is some poignancy in the Turnbull government’s rejection of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, a power response between grossly unequal parties.

While the author provides a logical argument for the rejection, the Uluru call is such an important part of Australia’s bigger picture that one would have liked to see more sensitivity in its treatment in A Bigger Picture. The Uluru Statement is about peace-making, about coming together after struggles of long duration. This includes jointly facing unpleasant facts about the past and making common commitments to peaceful co-existence in the future, whether through a treaty or a constitutionally recognised voice to parliament. Peace-making is the first cousin of dispute resolution and politicians have much to learn in this area.

Trust

In his final reflection Mr Turnbull indicates that he was, with the benefit of hindsight, too trusting of several of his colleagues, in particular Mathias Corman. In a Kafkaesque passage, here abbreviated by the reviewer to initials, he indicates that C and D told him not to trust J and G; J, G and C told him not to trust C and D; B told him not to distrust any of them; and everybody told him not to trust M.

Here DR 101 would have reminded the author about the prisoner’s dilemma lessons to be initially trusting on only minor issues instead of being over-trustful prematurely on major ones. In reality trust is a key factor in DR, whether the intervention is arbitration, conciliation or managerial fiat. Where trust is lacking between disputants trusted interveners can use their good offices to generate trust in the mediator or conciliator, and in the process at hand. Thus facilitators can assist parties fashion negotiated outcomes, such as between landlords and tenants in pandemic situations, by focusing them, wait for it …. on the bigger picture.

Influencers

Having suggested what politics might teach dispute resolvers (or reiterate for failing memories) concerning knowledge, skills and attitudes appropriate for DR, the question arises as to what the DR movement can contribute to post-pandemic politics. Many have written on this before, including Greg Rooney, Carrie Menkel-Meadow, the current writer and others.

Teachers and trainers of DR educate eager innocents about the differences between structural and behavioural aspects of conflict management. Mediation provides a structural framework premised on avoiding the adversarial partisan dynamics of litigation or arbitration, with procedures more appropriate for collaborative problem-solving. However structural changes do not alone sustain behavioural changes and old habits of positioning, posturing and punishing can and do prevail in mediation – a factor unanticipated by some eager innocents who become zealous mediation converts, for a while.

Restructuring a political system for the future is the task of political scientists, sociologists and constitutional lawyers – and politicians themselves. However dispute resolves would like to think that they can provide some potential influence on more collaborative, or at least less adversarial, structures and procedures for political engagement. This, after all, is their field of endeavour.

There do exist counter-adversarial arrangements in Australian politics: preferential voting avoids the ‘first-past-the-post’ syndrome of plurality elections and the Senate’s composition and powers require governments to negotiate continuously, at least with cross-bench or free-spirited Senators, to get their way. Other consensus inducing arrangements are functions of electoral politics and their outcomes, as opposed to constitutional requirements: coalition parties have to formulate consensual pacts and minority governments have to do compromise deals with independents or minor parties. These arrangements create non-adversarial elements in an overwhelmingly adversarial political system.

On what issues might the DR movement attempt to influence political systems into less structurally adversarial ways? Potential topics include:

- · Clear identification of issues in non-binary or partisan terms

- · Methods for introducing agreed factual reports and scientific expertise

- · Mandatory disclosure of information to enhance transparency

- · Scrutiny of and accountability for political promises

- · Grand coalitions (national cabinets?), veto systems and super majority requirements on identified issues

- · Further proportional representation in representative politics

- · Promoting a ‘voice to parliament’ as part of inclusive nation-building.

These are familiar factors in terms of how dispute resolvers design and shape conflict management systems with a view to attaining consensus and avoiding a winner-takes-all mentality. Mediators’ brain-storming powers might also suggest factors such as regular conscience votes, longer parliamentary terms and a federal ICAC with real teeth, as opposed to mere gums.

As to how dispute resolvers might influence the structures and procedures of government and politics, that is another big question. They could, however, start immediately with negotiation training for politicians. Reigning in a manic media would require more imagination.

Conclusion

A DR perspective provides limited insights into the author’s complex, intriguing and sometimes highly personal account of his life and politics. A book such as his also raises many questions, some of which have been posed in post-publication interviews with the author. As indicated earlier confirmation and hindsight biases are always at work in this literary genre. Nonetheless a major work by a former Prime Minister provides an intriguing chronicle of the times. And for dispute resolvers it provides some insights, and gentle reminders, about the use of prevention, interests, rights and power in disciplines other than their own.

—————————————-

The author is Professor Laurence Boulle, Principal of Independent Mediation Services Ltd and can be contacted at resolveaboulle@gmail.com He is grateful to Tony Spencer-Smith (www.expresseditors.com)for wise comments on an early draft. The usual exonerations apply.

Professor Boulle is Belle Wiese Professor of Legal Ethics at the Newcastle Law School (NSW). He has been Visiting Professor at Gent University in Belgium, the University of Capetown in South Africa and the University of the South Pacific in Vanuatu and Fiji. His most recent book with fellow ADRN member Rachael Field is Mediation in Australia.

The reality of the stressful nature of life in lockdown as a result of COVID-19 is that the quality of our communications and negotiations is under pressure. We need to harness our dispute resolution agency, and employ positive strategies and methods from the art of mediation, in order to ensure we do our best to prevent, manage and resolve disputes. We also need to practice self-management, for example by building our resilience skills, so that we protect our psychological well-being and ensure we have the right attitudes and energies for lockdown living.

The reality of the stressful nature of life in lockdown as a result of COVID-19 is that the quality of our communications and negotiations is under pressure. We need to harness our dispute resolution agency, and employ positive strategies and methods from the art of mediation, in order to ensure we do our best to prevent, manage and resolve disputes. We also need to practice self-management, for example by building our resilience skills, so that we protect our psychological well-being and ensure we have the right attitudes and energies for lockdown living.

Thank you: This series of posts was only possible through the collegial generosity of ADR Research Network members. Thank you to Professors Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander for very kindly allowing me to use and adapt Chapter 6 of their

Thank you: This series of posts was only possible through the collegial generosity of ADR Research Network members. Thank you to Professors Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander for very kindly allowing me to use and adapt Chapter 6 of their

Understanding stress

Understanding stress Intentionally managing our stress in lockdown involves quite practical, common sense approaches and strategies around building our resilience. Resilience is a capacity to cope well under pressure, as well as an ability to respond and endure in situations of adversity. In other words, resilience skills help us to manage and prevent stress.

Intentionally managing our stress in lockdown involves quite practical, common sense approaches and strategies around building our resilience. Resilience is a capacity to cope well under pressure, as well as an ability to respond and endure in situations of adversity. In other words, resilience skills help us to manage and prevent stress.

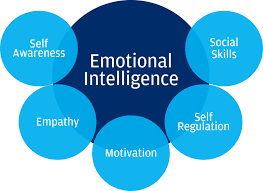

Simply put, emotional intelligence is the intelligent use of emotions. This requires an awareness of our emotions and an ability to use that awareness to beneficially aid our thinking and behaviour. Emotional intelligence informs our capacity to perceive emotions, assimilate emotion-related feelings, understand the information of those emotions, and manage them.

Simply put, emotional intelligence is the intelligent use of emotions. This requires an awareness of our emotions and an ability to use that awareness to beneficially aid our thinking and behaviour. Emotional intelligence informs our capacity to perceive emotions, assimilate emotion-related feelings, understand the information of those emotions, and manage them. Emotional contagion is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the ‘catchability’ or contagiousness of emotions. For example, if Rachael is in a particularly happy mood, this mood may end up rubbing off on Anna and Anna may subsequently begin to feel happier. Anna might then ‘infect’ others with her happiness. Emotional contagion ‘refers to the tendency to catch (experience/express) another person’s emotions’ (Kimura, Daibo and Yogo, 2008, 27).

Emotional contagion is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the ‘catchability’ or contagiousness of emotions. For example, if Rachael is in a particularly happy mood, this mood may end up rubbing off on Anna and Anna may subsequently begin to feel happier. Anna might then ‘infect’ others with her happiness. Emotional contagion ‘refers to the tendency to catch (experience/express) another person’s emotions’ (Kimura, Daibo and Yogo, 2008, 27). Emotional flooding occurs when an individual becomes swamped by emotions. Biologically, intense emotional experience can affect the way the brain works. Information exchange to the neo-cortex is inhibited, with the result that people find it difficult to think in cognitively complex ways and to function properly. This might sound like a really extreme and rare occurrence, but it actually happens to people surprisingly frequently.

Emotional flooding occurs when an individual becomes swamped by emotions. Biologically, intense emotional experience can affect the way the brain works. Information exchange to the neo-cortex is inhibited, with the result that people find it difficult to think in cognitively complex ways and to function properly. This might sound like a really extreme and rare occurrence, but it actually happens to people surprisingly frequently. The concepts of transference and countertransference have their origin in the work of Sigmund Freud and his focus on psychoanalysis/psychodynamic theory. Freud was a famous psychologist for many reasons, although when most people think about Freud, they often think about beards, couches, and unconscious and sexually repressed thoughts and behaviour. These images are all accurate to a certain degree. As it turns out, one of the reasons why Freud used ‘the couch’ when treating patients related to the notion of countertransference: ‘Freud frankly admitted that he used this arrangement inherited from the days of hypnosis, because he did not like “to be stared at”; thus, it served him as a protection in the transferencecountertransference duel’ (Benedek, 1953, 202).

The concepts of transference and countertransference have their origin in the work of Sigmund Freud and his focus on psychoanalysis/psychodynamic theory. Freud was a famous psychologist for many reasons, although when most people think about Freud, they often think about beards, couches, and unconscious and sexually repressed thoughts and behaviour. These images are all accurate to a certain degree. As it turns out, one of the reasons why Freud used ‘the couch’ when treating patients related to the notion of countertransference: ‘Freud frankly admitted that he used this arrangement inherited from the days of hypnosis, because he did not like “to be stared at”; thus, it served him as a protection in the transferencecountertransference duel’ (Benedek, 1953, 202). The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Rachael Field, James Duffy and Anna Huggins,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Rachael Field, James Duffy and Anna Huggins,

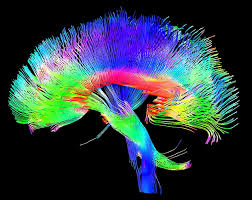

A compelling illustration of these insights is provided in relation to the phenomenon of loss aversion, one of the cognitive biases previously identified by psychologists. When subjects undergoing brain-scanning are exposed to the single words ‘loss’ or ‘gain’ there are profound differences in the observed neural impacts – in broad terms the former term has an effect several orders of magnitude greater than the latter, in respect of both intensity and duration. In this instance the brain science reinforces orthodoxy long prevalent in mediation theory: parties who perceive they are facing a loss are likely to be risk-accepting and seek an outcome away from the mediation, but if they perceive a gain at the mediation table they are likely to be risk averse and favour settlement. Brain scanning provides corroboration and a deeper explanation for the phenomenon, founded on human survival instincts, which responds to threats more intensely than to rewards. While survival instincts arose originally in relation to physical threats, they are now also a product of perceived unfairness, undignified treatment, negative emotional experiences or unfulfilled expectations in the mediation room.

A compelling illustration of these insights is provided in relation to the phenomenon of loss aversion, one of the cognitive biases previously identified by psychologists. When subjects undergoing brain-scanning are exposed to the single words ‘loss’ or ‘gain’ there are profound differences in the observed neural impacts – in broad terms the former term has an effect several orders of magnitude greater than the latter, in respect of both intensity and duration. In this instance the brain science reinforces orthodoxy long prevalent in mediation theory: parties who perceive they are facing a loss are likely to be risk-accepting and seek an outcome away from the mediation, but if they perceive a gain at the mediation table they are likely to be risk averse and favour settlement. Brain scanning provides corroboration and a deeper explanation for the phenomenon, founded on human survival instincts, which responds to threats more intensely than to rewards. While survival instincts arose originally in relation to physical threats, they are now also a product of perceived unfairness, undignified treatment, negative emotional experiences or unfulfilled expectations in the mediation room. Another dimension of brain science derives from the organ’s bicameral structure. In 2017 Australian judges were addressed on the divided brain by an English psychiatrist, Ian McGilchrist, his work drawing on science, philosophy, literature and culture. He accentuated the significance of brain bicameralism in many aspects of human affairs and societal development – and by implication in dispute resolution activities. A more dated ‘left brain-right brain’ notion had been prevalent decades earlier, associating the left with attributes such as logic, language and analysis and the right with factors such as emotion, affect and art. This construct had in some respects been overtaken by work on the triune brain, and its implications, referred to above.

Another dimension of brain science derives from the organ’s bicameral structure. In 2017 Australian judges were addressed on the divided brain by an English psychiatrist, Ian McGilchrist, his work drawing on science, philosophy, literature and culture. He accentuated the significance of brain bicameralism in many aspects of human affairs and societal development – and by implication in dispute resolution activities. A more dated ‘left brain-right brain’ notion had been prevalent decades earlier, associating the left with attributes such as logic, language and analysis and the right with factors such as emotion, affect and art. This construct had in some respects been overtaken by work on the triune brain, and its implications, referred to above. John Wade used the metaphor of the mediator’s tool-box of interventions, implying that mediators will not always be able to adopt standardised procedures and linear logic but may have to be reactive, responsive and instinctive in using different tools in the process. The National Mediator Accreditation System provides some guidance on mediator responsibilities in relation to conflict, negotiation and culture but this is of only limited proportions. Psychology and neuro-science are definitely new tools for the mediator’s tool-box.

John Wade used the metaphor of the mediator’s tool-box of interventions, implying that mediators will not always be able to adopt standardised procedures and linear logic but may have to be reactive, responsive and instinctive in using different tools in the process. The National Mediator Accreditation System provides some guidance on mediator responsibilities in relation to conflict, negotiation and culture but this is of only limited proportions. Psychology and neuro-science are definitely new tools for the mediator’s tool-box.

In acting as an agent of reality, a key strategy to help the parties consider whether a settlement or solution is realistic and viable is to question them about what the proposed solution would look like in operation in the context of their lives outside mediation, helping them to cogently and realistically think through the risks, options and choices available to them.

In acting as an agent of reality, a key strategy to help the parties consider whether a settlement or solution is realistic and viable is to question them about what the proposed solution would look like in operation in the context of their lives outside mediation, helping them to cogently and realistically think through the risks, options and choices available to them.

Some of the content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.57-6.58 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you – Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities. The post also includes content from Laurence Boulle and Rachael Field, Mediation in Australia (LexisNexis, 2018) 104-5.

Some of the content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.57-6.58 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you – Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities. The post also includes content from Laurence Boulle and Rachael Field, Mediation in Australia (LexisNexis, 2018) 104-5.