In posts # 17 and 18 we discussed the mediator’s tool of reframing. Reframing is the third of the five elements of the communication skill set represented by the acronym LARSQ – after listening and acknowledging. This post looks at how mediators use the fourth element of LARSQ – summarising – when they practice the art of mediation to support parties in their efforts to constructively communicate and problem-solve. We also discuss the related skills of paraphrasing and reiterating. In lockdown we can put these skills into practice as we endeavour to prevent, manage and resolve disputes.

Summarising

A summary of what the person we are communicating with has said is a useful way to ensure that there is an accurate developing account of the conversation and it can be a way of demonstrating to that person that they have been heard properly and understood.

In mediation practice, summarising generally involves a mediator briefly restating or recapping important features of the preceding discussion and identifying the dominant feelings of both parties.

Summarising can be a powerful intervention in mediation – as well as in our lockdown communications – because it can achieve a range of positive objectives. For example, summarising can:

- Provide a neutral and organised version of a sequence of discussion.

- Emphasise vital issues which might otherwise have been overlooked.

- Simplify convoluted exchanges.

- Remind people that progress is being made.

- Signpost how that progress is being made and reaffirm the common direction of the discussions.

- Provide acknowledgment to people that they have been understood.

- Establish a bridge into the next round of discussions.

- Assist with establishing trust between people by using – in the summary – some of the key words they have said.

Good summarising requires a range of micro-skills, such as retaining important information, recalling it and condensing it. It is always a selective process in that in a mediation, mediators pick up on positive progress to date and present it in a constructive and concise statement. It is also selective in that mediators pick up only on what is useful for the communications – not everything gets summarised. The reason why mediators are selective in enacting the summarising process is that selectivity allows them to create a positive and encouraging basis for the parties to move forward with their negotiations. However, summaries also need to be balanced in the sense that they deal fairly with what each side has said.

Good summarising requires a range of micro-skills, such as retaining important information, recalling it and condensing it. It is always a selective process in that in a mediation, mediators pick up on positive progress to date and present it in a constructive and concise statement. It is also selective in that mediators pick up only on what is useful for the communications – not everything gets summarised. The reason why mediators are selective in enacting the summarising process is that selectivity allows them to create a positive and encouraging basis for the parties to move forward with their negotiations. However, summaries also need to be balanced in the sense that they deal fairly with what each side has said.

In their book Mediation Skills and Techniques master mediators Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander provide an example of summarising in action. The example is based on a hypothetical dialogue from a mediation involving a widow and a relative of her deceased husband in relation to the distribution of his estate. The deceased’s wife, Mrs Rona Steele, is negotiating with a distant cousin, Ms Gabriella Gold, as a step prior to distribution of the estate of the late Mr Rod Steele.

Mediator: ‘Now, Mrs Steele, you’ve told us that you initially found it difficult to negotiate with Ms Gold because you felt that she could have dealt with you more humanely and sympathetically. You also said that while you might not be able to resolve all your personal differences, you are prepared to offer Ms Gold a small portion of Mr Steele’s estate. And, Ms Gold, you acknowledged that you could have handled things differently with Mrs Steele and demonstrated greater empathy for her loss. You also explained the pressures you are under at home and said that you would be prepared to consider a financial offer from Mr Steele’s estate as opposed to receiving the hand-crafted antique furniture you originally requested. Is that correct …? Now, Mrs Steele and Ms Gold, let’s move forward and look at how we can craft a financial arrangement that you can both live with …’.

Summarising is useful throughout a process of communicating or negotiating. At the very least, there is great value in being clear that each person’s positions, needs and interests have been accurately understood. Summarising is also useful if there has been a break in communications – it allows everyone in the conversation to revisit where the discussions got to before the break occurred and serves to refocuses people. Summarising can also be used when there is an impasse in communications or negotiations. In this situation it has the function of emphasising the positive progress that has been made to date and providing building-blocks for future dialogue and negotiation.

Good summarising can be one of the most effective interventions for mediators and is an essential tool in their mediation toolbox.

Paraphrasing

In a mediation, mediators use paraphrasing to closely control the dialogue between the parties and to pick up on important issues and reflect the salient points in the mediator’s own words. Mediators focus on factors that are evidently important to the parties such as major concerns, interests, needs and feelings, thereby ensuring there is a response to these aspects of each party’s message. Because paraphrasing involves the mediator intervening in the dialogue with clarifying and empathic questions, and in summarising and reframing some of the conversation, it requires delicacy and discretion in choice of language.

Here is an illustration of the paraphrasing method based on the hypothetical discussion mentioned above:

Mediator: ‘Ms Gold, Mrs Steele is saying that although you may be justified in making a claim on the estate, the way you have approached this has caused her a great deal of pain, suffering and sadness. I’m wondering how you would like to answer her on that …?’

Ms Gold: ‘Yes, look … you have my deepest sympathy at this time. I know you and Rod loved each other and it must be really hard for you. Sorry if my manner has upset you. Rona, you were always good to me when I visited, you had an open door and listened to my woes. Sadly, this situation is no different … My partner has left me and taken all the furniture. He just cleared out the house. You know I don’t work and have four children to feed … I am desperately in need of support.’

Mediator: ‘Mrs Steele, Ms Gold has expressed her regret at the upset she has caused you. She has acknowledged the close relationship that you and Mr Steele had and how bereft you must feel at his loss. Ms Gold also emphasised how good you have been to her in the past. Can you tell her how you feel now that you have heard that …?’

Mrs Steele: ‘Well, it’s the first time I’ve ever heard words of kindness from Gabriella … But I am still not willing to part with any of the antique furniture that Rod’s great-grandfather hand-crafted …’.

In a mediation, mediators ensure that paraphrasing is done in an even-handed way so that both the parties’ communications are paraphrased. In this way, it can be used to set up a pattern of direct communication between parties, and it can break what Australian mediation legends Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney have called the ‘Oh but’, ‘Yes but’ pattern of communication: ‘Oh but I didn’t understand that’s what you wanted.’ ‘Yes but I had told you only two days before …’. ‘Oh but I called and texted you …’ ‘Yes but …’ (2014: 250). However, if this is the only way of keeping parties communicating constructively it can quickly become strained and artificial.

In a mediation, mediators ensure that paraphrasing is done in an even-handed way so that both the parties’ communications are paraphrased. In this way, it can be used to set up a pattern of direct communication between parties, and it can break what Australian mediation legends Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney have called the ‘Oh but’, ‘Yes but’ pattern of communication: ‘Oh but I didn’t understand that’s what you wanted.’ ‘Yes but I had told you only two days before …’. ‘Oh but I called and texted you …’ ‘Yes but …’ (2014: 250). However, if this is the only way of keeping parties communicating constructively it can quickly become strained and artificial.

Reiterating

In mediation practice, mediators need to prevent anything of value ‘falling off’ the negotiation table. In the heat of the moment it is possible for an apology, a concession or a significant offer to go unheard by the listening party because of their anger, psychological deafness or intent on winning. Here it is wise for mediators to ask the speaker to repeat the value statement, when the timing is appropriate for this intervention. For example: Mediator: ‘Nigel, I think you were making an offer in terms of compensation a few moments ago, when we got side-tracked by the question of Karlie’s health. I’m wondering if you would like you to repeat that offer now …’.

Alternatively, mediators might themselves reiterate the statement of value when circumstances allow, for example: Mediator: ‘A few minutes ago I heard Nigel say that he would print a formal apology in the forthcoming Sunday paper. Is that correct, Nigel?’

Reiteration can be used to step up a weak signal from one party that is not being heard by the other, for example: Mediator: ‘Karlie, Nigel has indicated on a number of occasions that the story is not a personal attack on you nor on your work as an artist, which he says he admires very much. Is that what you have heard also?’

Generally, reiteration is one of the tools in the mediator’s toolbox which can be used in all situations in which parties are talking past each other and not picking up on important messages.

Generally, reiteration is one of the tools in the mediator’s toolbox which can be used in all situations in which parties are talking past each other and not picking up on important messages.

LARSQ is certainly a significant skill set for mediators. Enacting the elements of LARSQ can also support quality, constructive communications in our daily lives – especially when we are faced with challenges such as lockdown. Posts 20 and 21 complete our sequence of posts considering LARSQ – they focus on appropriate questioning.

Tomorrow’s Blog: Lockdown Dispute Resolution 101 #20: Effective communication strategies in lockdown – appropriate questioning: Part 1

Acknowledgements

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.60-6.66 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you – Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities.

See also: Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney, The Mediator’s Handbook: Skills and Strategies for Practitioners (The Law Book Co, 3rd ed, 2014).

See also: Ruth Charlton and Micheline Dewdney, The Mediator’s Handbook: Skills and Strategies for Practitioners (The Law Book Co, 3rd ed, 2014).

Summarise image 1: The Ideal Teacher

Summarise image 2: GSA Learning Support

Summarise image 3: Adventures with Miss B

Paraphrasing image 1: Virtual Library

Reiterating image 1: Spinfold

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.47-6.54 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities.

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander, Mediation Skills and Techniques (LexisNexis, 3rd ed, 2020) paras 6.47-6.54 with the kind permission of the authors. Thank you Laurence and Nadja! Both Laurence and Nadja are esteemed members of the ADR Research Network and have long been leaders in the Australian and international dispute resolution communities.

When mediators reframe, they are engaging in a translation exercise through which they change the communication by moving it from one type of language to another. The intention is that the second language version is more palatable to the parties and more conducive to collaborative problem-solving.

When mediators reframe, they are engaging in a translation exercise through which they change the communication by moving it from one type of language to another. The intention is that the second language version is more palatable to the parties and more conducive to collaborative problem-solving.

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

As human beings, we all have a basic capacity for empathy, and we are also socialised to extend that capacity because in every culture, even though empathy may manifest in diverse ways, some level of empathy is important to the quality of human relations. In order to harness the communication benefits of empathy, we must be present in our communications with others, paying attention and prepared to engage and connect. Listening empathically means that we are focused on what the other person is saying, observing, feeling, needing and requesting.

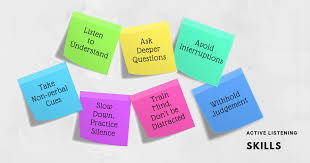

As human beings, we all have a basic capacity for empathy, and we are also socialised to extend that capacity because in every culture, even though empathy may manifest in diverse ways, some level of empathy is important to the quality of human relations. In order to harness the communication benefits of empathy, we must be present in our communications with others, paying attention and prepared to engage and connect. Listening empathically means that we are focused on what the other person is saying, observing, feeling, needing and requesting. This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of

This next sequence of posts continues our learning from the theory and practice of mediation – with an emphasis on specific skills for effective communication. We are focussing on five key skills denoted by the acronym LARSQ. LARSQ stands for listening, acknowledging, reframing, summarising and questioning. The LARSQ approach to understanding and enacting effective communication is a common feature of  Effective listening

Effective listening

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,

The content of this post was adapted and reproduced from Laurence Boulle and Nadja Alexander,  See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

See also: Mieke Brandon and Leigh Robertson, Conflict and Dispute Resolution: A Guide for Practice (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Perceptions and subjectivity are therefore important factors in conflict and disputes. However, conflict situations with the potential to turn into concrete disputes may not do so because they exist only in the perception of one or both parties and not in actual reality – for example two employees perceive themselves to be competitive rivals for one position whereas neither is realistically in line for it. This can be referred to as pseudo conflict in which parties’ perceptions or expectations are false or based on incorrect fears or unjustified apprehensions. False conflicts are based on stereotypes about others in terms of their personal or group attributes, for example about management or unions, or about refugees and security officials, and these can be accentuated by continuing ignorance or withholding of information, or by rumours, confirmation biases and wilful blindness. There may be little basis to the conflict in reality but it is played out by one or more parties as if there was. With both pseudo conflict and false conflict, the sharing of correct information, the provision of an explanation, or righting a misperception or a misunderstanding can help to resolve the situation.

Perceptions and subjectivity are therefore important factors in conflict and disputes. However, conflict situations with the potential to turn into concrete disputes may not do so because they exist only in the perception of one or both parties and not in actual reality – for example two employees perceive themselves to be competitive rivals for one position whereas neither is realistically in line for it. This can be referred to as pseudo conflict in which parties’ perceptions or expectations are false or based on incorrect fears or unjustified apprehensions. False conflicts are based on stereotypes about others in terms of their personal or group attributes, for example about management or unions, or about refugees and security officials, and these can be accentuated by continuing ignorance or withholding of information, or by rumours, confirmation biases and wilful blindness. There may be little basis to the conflict in reality but it is played out by one or more parties as if there was. With both pseudo conflict and false conflict, the sharing of correct information, the provision of an explanation, or righting a misperception or a misunderstanding can help to resolve the situation.

Future Time, Future Space

Future Time, Future Space Conflict is a challenging phenomenon in all contexts – in international relations, societies, families and workplaces. It is pretty much endemic to the human condition and is usually present in some form or at some level wherever human beings are in a relationship or relating to each other in some way. In one of our books on dispute resolution – Australian Dispute Resolution: Law and Practice – Laurence Boulle and I deal extensively with the many facets of conflict and disputes: the definitions, sources and dimensions, how they can escalate and de-escalate, and possible interventions and outcomes. This post is taken from that Chapter.

Conflict is a challenging phenomenon in all contexts – in international relations, societies, families and workplaces. It is pretty much endemic to the human condition and is usually present in some form or at some level wherever human beings are in a relationship or relating to each other in some way. In one of our books on dispute resolution – Australian Dispute Resolution: Law and Practice – Laurence Boulle and I deal extensively with the many facets of conflict and disputes: the definitions, sources and dimensions, how they can escalate and de-escalate, and possible interventions and outcomes. This post is taken from that Chapter.

The term complaint is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘dispute’. However, the term is usually associated with consumers or clients alleging wrongdoing or irregular practices by business, government or other service-providers.

The term complaint is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘dispute’. However, the term is usually associated with consumers or clients alleging wrongdoing or irregular practices by business, government or other service-providers. The term grievance is often used in workplace and employment contexts where it is used to refer to allegations of various kinds made by employees against employers, supervisors or other employees. The term ‘grievance’ usually implies that there has been a lack of response, or even resistance, from management – for example a supervisor has not responded to allegations of victimisation, the HR department has not addressed bullying concerns or there has been failure to performance manage an employee adequately. Grievances can arise out of conflict situations and could give rise to concrete disputes that require legal interventions such as fact-finding investigations or tribunal hearings. Where an employee brings a grievance claim there could follow a process of investigation, mediation and adjudication in relation to their rights as employees and the alleged wrongdoing of other parties in the workplace.

The term grievance is often used in workplace and employment contexts where it is used to refer to allegations of various kinds made by employees against employers, supervisors or other employees. The term ‘grievance’ usually implies that there has been a lack of response, or even resistance, from management – for example a supervisor has not responded to allegations of victimisation, the HR department has not addressed bullying concerns or there has been failure to performance manage an employee adequately. Grievances can arise out of conflict situations and could give rise to concrete disputes that require legal interventions such as fact-finding investigations or tribunal hearings. Where an employee brings a grievance claim there could follow a process of investigation, mediation and adjudication in relation to their rights as employees and the alleged wrongdoing of other parties in the workplace.