Age and Mediation Part II

My last blog ended with the question of how mediation might have helped Edith Hill, a 96-year-old African-American woman. As told by documentary filmmaker Laura Checkoway and journalist Judith Graham, her story includes factors familiar to elder mediation proponents. These include longstanding family conflict, loving adult children, allegations of financial abuse that were raised but not resolved through a legal process, and debate over how to best identify and support cognitively impaired and highly dependent adults. Mediation has been theorized to empower older adults in these situations by providing greater opportunity for direct participation and for warring loved ones to focus on finding the best way to provide care.

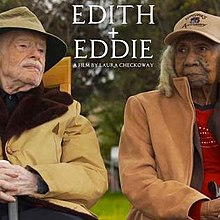

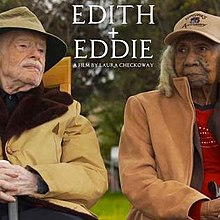

In the documentary of Edith and her husband Eddie, a heartwarming story of the world’s oldest interracial newlywed couple is ended by heartbreaking separation. Edith and Eddie have no recourse in the face of a professional guardian’s authority to move Edith to another state. Eddie dies a couple weeks later.

Would mediation have helped? Given that no attempt was made, any argument is one of speculation. As a relatively new specialization, elder mediation is still developing its empirical foundation. The purpose of this blog post is to help move from theory to practice by briefly presenting results from study of elder mediation pilot projects in Ghana and the United States. I first explain why the elder advocacy agency in each research site pilot tested mediation. I then briefly present from my study and findings to end with a more empirically based guess as to whether mediation could have helped Edith Hall.

Research sites

In both countries, the primary research sites selected were elder advocacy agencies. Each had identified mediation as potentially empowering for older adults. In Ghana, the goal was to improve the cultural sensitivity of an elder rights program. The concern was that most legal cases violating the rights of older adults would involve family, and that mediation was more culturally appropriate than formal legal intervention. In the U.S., one goal was to build from adult guardianship mediation. Was it possible to keep cases out of court through mediation referral and thus obviate unnecessary guardianship appointments? The other was to continue testing the benefits of mediation in adult guardianship cases. The U.S. elder advocacy agency partnered with mediation professionals and court services in three states with outreach efforts to potential referral sources, such as clergy, hospice workers, and geriatric case managers.

Research design

A qualitative, ethnographic approach was used given the exploratory nature of both projects. In neither research site were enough cases generated to allow more standard program evaluation. My project was therefore adapted to ask more basic questions, such as how to explain the gap between professional anticipation of need and low caseload results. Over time I also questioned the underlying presumptions of an elder advocacy discourse in which chronological age was conflated with vulnerability, loss, and dependency (Crampton 2016).

https://pixabay.com/en/old-couple-sitting-grandparents-2313286/. ErikaWittlieb

Was this culturally resonant with the lived experience of those aged 60+? I approached these questions primarily through the participant observation methods of anthropological field research.

Research findings

In both countries, one explanation for low caseload was the presence of alternatives. In Ghana, people commonly seek third parties who convene a meeting to resolve disputes without resorting to a formal legal process (Crampton 2006). However, the third party is more typically a respected member of an organization (such as a company) or a community (such as the head of an extended family) whose expertise is known through seniority and demonstrated maturity. Formal training and mediation professionalization was new during data collection (2004-5). While the elder advocacy agency was interested in professionalization, they had already provided dispute resolution intervention for older adults seeking help through a community development officer. And, they had previously resolved conflicts among older adults using their services without professional mediation training. During the research period, I followed a dispute brought by an older adult to his local chief. Meanwhile, the European donor for the legal rights program did not expand project parameters to ADR services.

In the U.S., the presence of alternatives to mediation came from professionals and creative avoidance by older adults. Despite extensive outreach, professionals who worked with older adults agreed with purported benefits but felt no need to refer cases given their own expertise. Meanwhile, one of the mediation program partners found that older adults were particularly reluctant to agree to mediation. They wanted to keep family conflict private. This changed when cases went to court, and mediation became the more private alternative. In my field research, I found that people in the U.S. avoid the stigma and loss associated with growing older by refusing services specifically targeted to “elders” and “older adults.” In one case, for example, an older adult refused professional intervention and yet relied on neighbors, church members, and her therapist for support as she grew frail and dependent. She found overnight caregivers by placing an ad in a local newspaper. This reminded me of a phrase learned from one older adult, “Old age is just a number and mine is unlisted.” How are “elder” mediation services best offered to people aged 60+ who balk at identification as an “older” adult?

Lessons learned

Would mediation have helped Edith and Eddie? Answering this question might start with asking why mediation was never part of the story. At least one court and several lawyers were part of the guardianship case. Was there consideration of mediation referral? Were attempts made but ultimately refused? Answering these questions would help ground the answer from one of theory to case specifics. From my observations as a researcher, I think that mediation could have been a less traumatic way to resolve conflict over whether Edith would move back to Florida. However, this option requires consent from several parties, expertise in how to include Edith (and Eddie), and ensure that her best interests were met, and time invested to work through the emotions and practical complications of caregiving by three adult children living in different states. In other words, moving from theory to practice requires realistic assessment of how to get to a lot of “yes” answers before mediation sessions begin.